- AROUND THE SAILING WORLD

- BOAT OF THE YEAR

- Email Newsletters

- Best Marine Electronics & Technology

- America’s Cup

- St. Petersburg

- Caribbean Championship

- Boating Safety

Downwind Tactics For Planing Conditions

- By Carlos Robles

- October 10, 2022

Anytime the wind picks up enough that we get to plane downwind, there’s huge opportunity to make gains. When boats start to plane, differences in speed between a fast and a slow boat could be in excess of 4 knots, or 6 feet per second. In other words, you could gain or lose 300 feet in less than a minute. Therefore, it is important to have in mind the following priorities when planing conditions are in play.

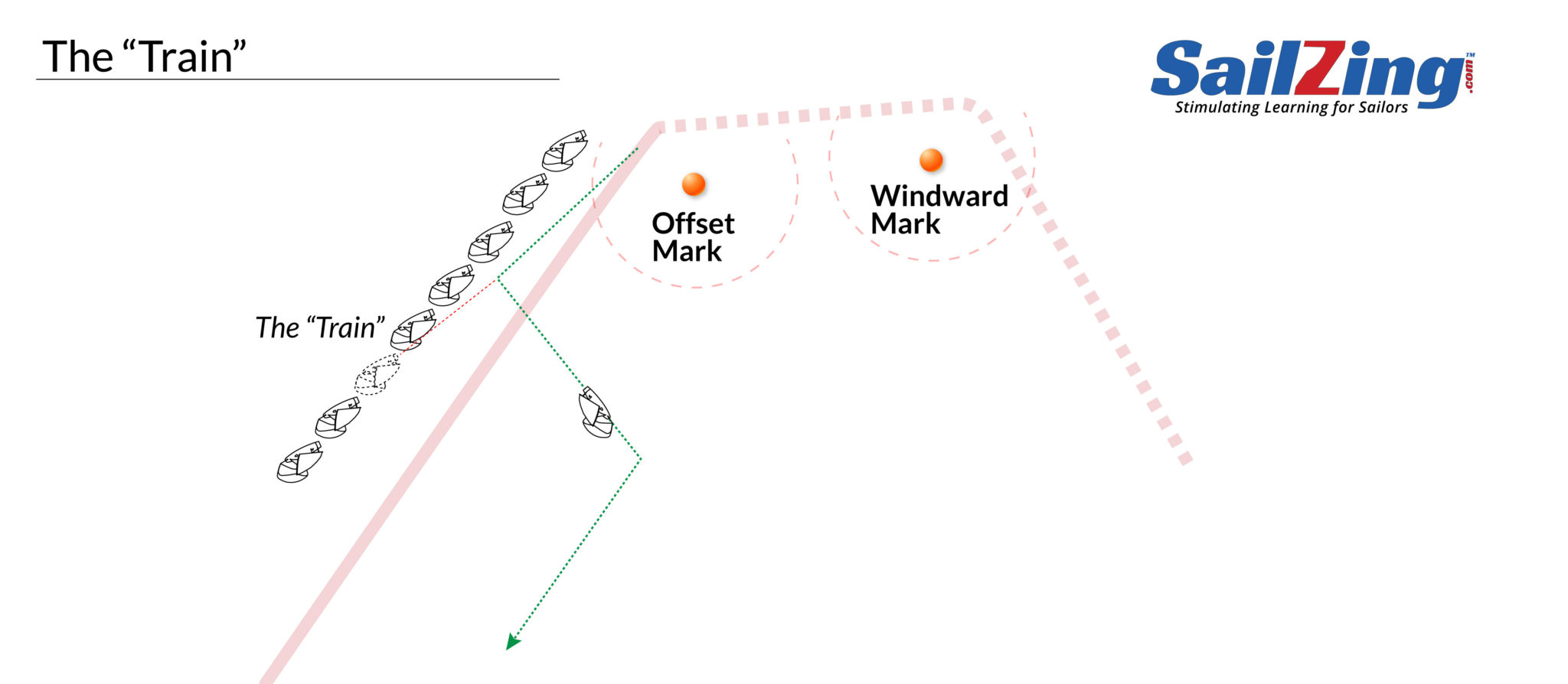

1. Set yourself up for a clean hoist and exit at the weather mark

Mark roundings are where the most gains or losses happen. When you get tangled up with another boat, it’s easy to get stuck sailing below target speed while other boats are planing away at full speed. It is, therefore, important to anticipate the exit and have this conversation with my team (or yourself, if you’re sailing a singlehander) in the last third of the upwind leg. Ask yourself the following questions: Is the top mark going to be busy with traffic, or is the fleet spread out? What’s happening on this upwind beat and what side of the downwind is priority to defend? Is jibe setting an option? It could very well be that a jibe-set will keep you on the favored side of the downwind leg, but also think about staying in clear breeze and how far there wind shadow extends, especially if there’s a long offset leg. Sailing across a long wind shadow might be too big of a price to pay, so assess these factors, make a clear exit plan, and execute it successfully.

If it’s going to be a straight set, look around while you’re on the offset leg. If there’s space and you are not overlapped with boats around you, a clean bear-away and hoisting the kite at a low angle will work. If you are overlapped with boats to windward as you round the weather mark, delay the hoist if necessary and continue sailing on a broad reach across the offset leg. The key here is to make sure the boats to windward are not going to roll you before bearing away. As the leeward boat, you will decide when to put the kite up!

If you’re overlapped with boats to leeward, or if there is a big pack close ahead, holding a high-lane hoist becomes super powerful. I call it the high-road set. Hold for a few seconds and set yourself up to windward of these boats, this becomes very powerful when straight setting and holding a lane is the only option. Boats ahead of you that set early will have a difficult time trying to head up to get to your lane and any little gust of wind will favor this higher lane, allowing you to sail fast all the time.

If the goal is to jibe set or jibe early, make sure you are not overlapped with boats inside you as you round the weather mark. It will be a priority on the offset leg to break this overlap (either by rolling over the top of the boats to leeward or slowing down to let them get ahead in front of you but not overlapped). This will allow you to have the option to jibe at the mark or beat them to the jibe later on the run.

2. Always anticipate the next move

Think ahead because things happen fast at the top of the run and you should always remind yourself about what is coming next. Ask yourself: When are we going to jibe next? Do we want to lead this jibe, or wait and go to the layline? Keep in mind that maneuvers at high speeds are usually costly. So, jibing a few times down the middle of the course does not pay in most cases.

3. Be very confident with your layline judgement

For any boat I sail, I like to pick my references for laylines for each true windspeed. It is important to do this during training. In planing conditions, knowing exactly where the layline is will be crucial. You can use parts of the boat to determine this exit angle. I usually eyeball the downwind mark and try to align it with some part of the boat. For example, if the mark is aligned with the lower shroud in planing conditions, I know the layline is imminent. Make sure you always call the layline from the same exact position onboard so references are trustworthy. A good way to refresh this is by doing this exercise before the start, or on the way to the racecourse when going downwind. Use the race committee boat, a channel marker or any other fixed object as a mark to judge your layline call before the race starts. It is surprising the amount of boats that will fail to judge this correctly, opening up huge passing opportunities, especially at the bottom of the downwind leg.

4. Prioritize pressure over shift

If you want to plane, you’re looking for dark-water spots, so the goal is always to pick a good lane and make sure you jibe into dark spots. On gusty days, a good trick to know when to jibe to stay in pressure is by eyeballing your exit angle on the opposite jibe. Will there be dark water there? Maybe waiting to jibe another 30 seconds will keep you in more wind for longer.

5. Set yourself up to plane into the weather mark

Just like at the upwind mark, the same concepts apply when rounding a gate or a leeward mark. Again, assess the situation based on traffic around you, clean breeze and wind pressure. If you’re planing, which is the goal, you want be able to hold that speed for as long as possible. So, often it’s better to take the less favored gate mark as long as it keeps you in clean wind, clear of wind shadows, and in less traffic, which will allow for a better rounding in more wind, getting your team to upwind target speed in a shorter time.

About Carlos Robles

Robles, Born in Barcelona, Spain in 1995 is a 27-year-old sailor based in the USA. Son of a Spanish father and a Brazilian mother, Carlos was introduced to sailing at age 5 by his dad in their 30 foot family boat. From being part of the Spanish Sailing Team since the age of 9 and later on the Brazilian Olympic team, the passion to become a re-known professional sailor was always his primary focus. At his young age Carlos’s resume includes three World Championships and a European Championship in the 29er class and an Olympic Campaign in the 49er class representing Brazil, where he became North American Champion in 2016. Since transitioning into professional sailing in late 2019, Carlos is already a two-time North American Champion and European Silver Medalist in the J7/0 class, he finished second at the Melges 24 World Championships this year and second again at the J/111 North Americans. He also enjoys going offshore in bigger teams, racing around Europe in 2021 in the Volvo 65 class and finishing second at the Newport to Bermuda Race in the Pac 52 class this year. You can find him at @carlosrobleslorente and on Facebook as Carlos Robles.

- More: Racing , Tactics

- More Racing

Reineke’s Battle For the Berth

One-Design Wingfoil Racing Takes Off

Brauer Sails into Hearts, Minds and History

Anticipation and Temptation

America’s Offshore Couple

Jobson All-Star Juniors 2024: The Fast Generation

- Digital Edition

- Customer Service

- Privacy Policy

- Cruising World

- Sailing World

- Salt Water Sportsman

- Sport Fishing

- Wakeboarding

Downwind Sailing - 3 Fundamental Skills

The downwind leg of a sailboat race offers some of the greatest opportunities for overtaking. In downwind sailing, there was once a time when sailors simply let out the sails and took it easy, relying on the wind and waves to propel the boat forward. Olympic legend from Denmark, the four-time gold medallist Paul Elvstrom changed all that when he started really ‘working’ his Finn dinghy down the waves, and starting ‘pumping’ the mainsail. Ever since then, sailors have pushed their boats harder and harder downwind. Here we’ll look at some of the fundamentals of downwind sailing.

Optimal wind flow across the sails in downwind sailing

The great thing about sailing downwind is that even if you do nothing and let the sails flap, the wind will push you further downwind. Unlike sailing into the wind where you really have to know the fundamentals of sailing to get the boat to move upwind, downwind you really don’t have to be that skilled to get the boat moving in the right direction.

Let’s say you’re sailing a basic singlehanded dinghy like an Optimist, Laser, ILCA or something similar. If you point the boat directly downwind and let the sail out to 90 degrees, the boat will move reasonably well through the water because you’ve got maximum projected area catching the wind. You’re treating the sail as a windbreak, the telltales maybe stalled, but you don’t care because you’re sailing the shortest distance from A to B.

In downwind sailing, even on a fairly slow boat like a Laser, it’s always faster to generate airflow across the sail. Keep the boom at 90 degrees, don’t adjust the sheeting. But now luff up or bear away by the lee until you can see the telltales start to stream horizontally across the mainsail. Even though you’re not sailing downwind directly, and potentially travelling a greater distance through the water, the increased efficiency of the sail will more than justify the extra distance with higher boatspeed.

Observe an Olympic fleet of Lasers/ILCAs during downwind sailing, and you'll notice the dramatic steering by sailors, initially sailing by the lee, then slightly headed up, and returning to sailing by the lee again, all while avoiding sailing directly downwind.

Surfing the waves in downwind sailing

Are you sailing faster than or slower than the waves? Laser Olympic Champion from Great Britain, Paul Goodison, says this is a crucial question to ask yourself when sailing downwind.

Slower than the waves?

If the wind is light and you’re going slower than the waves: look behind you and search for the highest bit of the wave to give you a push before it disappears underneath the boat and out in front of you. You’re looking for the biggest push that the wave will give you. Look to either side of you and constantly search for the best wave to give you a helping hand. Luff up or bear away, whatever takes you towards the best part of the wave.

Faster than the waves?

If the wind is stronger, perhaps even strong enough to get your boat up and planing, everything changes. Now, if you’re going faster than the waves, you’re looking for the lowest ‘on ramp’ to the wave in front of you. This time your wave focus is always looking forward and to either side, either luffing or bearing away to find the lowest, easiest part of the wave to catch the waveset in front of you. Once you’ve broken through to the next wave, no time to relax! Now you’re looking for the next on-ramp to the next wave, and so on until the leeward mark.

Aim for the gust

Another factor that you need to keep in mind all the time is where is the strongest wind behind you? If you see more wind coming down one side of the course, steer in that direction to pick up the gust as early as possible. Using a wind sensor can help you identify the direction of the gusts more accurately. Once you’re in the gust, steer to ride the stronger breeze as long as possible, even gybing if you have to.

Sailing with spinnakers and asymmetrics in downwind sailing

So far we’ve been focusing on the dynamics of downwind sailing in slow, conventional boats. Much of the same principles apply to faster boats, but there are some big differences too. Which is why we’ll talk about those in other blog posts.

Downwind sailing: putting it all together

Let’s remind ourselves of the three key factors in downwind sailing we’ve talked about in this post: - Creating airflow across the sail - Steering for the best part of the wave - Aiming for the strongest breeze

Put these three dynamics together and you’ve got the makings of good downwind speed. It can seem like a dark art to begin with. So much of good downwind pace is about ‘feeling’ the boat, ‘feeling’ the waves. That only comes with a lot of practice and time on the water. Once you’ve got that feel, you’ll have a superpower that will supercharge your performance when sailing downwind. It’s one of the best ways to come back from a bad start or first beat. And overtaking multiple boats with superior downwind sailing speed is one of the greatest experiences in sailboat racing. Watch our webinars Try out some of the tips and tricks we’ve outlined in this article. Notice what works and what doesn’t. Don’t be afraid to experiment with new ideas in your sailing training. There’s a lot more race-winning info in our series of Webinars. Join in (for free) with Sailmon’s live webinars where we have some of the very best sailors in the world sharing their go-faster tips with the audience from around the world. Even if you can’t make it to the live session, all the recordings are on Sailmon.com

Recent Posts

Sign up for our newsletter.

- Find A School

- Certifications

- North U Sail Trim

- Inside Sailing with Peter Isler

- Docking Made Easy

- Study Quizzes

- Bite-sized Lessons

- Fun Quizzes

- Sailing Challenge

Mastering Sailboat Racing Tactics: A Winning Approach

By: Zeke Quezada, ASA Sailing Races

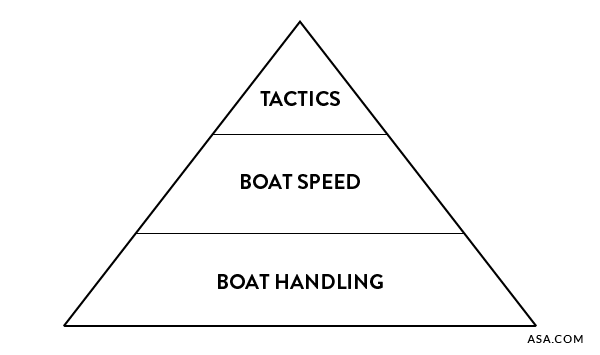

Sailboat racing demands a unique blend of skills and expertise. The dynamic nature of racing, with its ever-changing winds and currents, requires sailors to excel in various aspects to secure victory. One of the biggest challenges is dealing with the fluid playing field upon which we play. At North U, experts understand that sailboat racing success is built on a pyramid comprising Boat Handling, Boat Speed, and Tactics, with Tactics reigning supreme at the pinnacle.

Building the Foundation: Boat Handling and Boat Speed

Before delving into the intricacies of racing tactics, it’s crucial to lay a solid foundation. Boat Handling forms the base of the pyramid, emphasizing the importance of mastering the art of sailing. Without proficient boat handling skills, even the best tactics would falter. Next in line is Boat Speed, a universal requirement across all forms of racing. Whether it’s bicycles, bobsleds, or sailboats, speed is the essence of victory in any race.

Reaching the Summit: Racing Tactics

Atop the Racing Pyramid stands Tactics, the ultimate decider in the world of sailboat racing. Once you’ve honed your boat handling and achieved exceptional speed, mastering tactics becomes the key to clinching victories. Tactics, in its broadest sense, encompasses Strategy and Tactical execution, each playing a pivotal role in the race.

Understanding Strategy and Tactics

Strategy is the overarching plan that revolves around wind, wind shifts, and current. It is an overall gameplan detailing how a sailor would navigate the course independently while factoring in the complex interplay of natural elements. On the other hand, Tactics involve the practical implementation of the strategy and the adept handling of other boats in the race. Understanding and adhering to Racing Rules are part of Tactics, as the rules dictate your rights and obligations as you deal with other boats.

General Tactical Tips:

- Craft a Comprehensive Strategy: Formulate a game plan based on your expectations of the wind’s behavior. A well-thought-out strategy provides a roadmap for your race.

- Get a Good Start: While a perfect start is ideal, it’s not mandatory for victory. Focus on launching at full speed from the starting line, ensuring you have clear air near the favored end. A strong start sets the tone for the race.

- Chase the Wind: Seek out areas with more wind and navigate your boat towards these pockets. Sailing in favorable wind conditions gives you a significant advantage over competitors.

- Embrace Speed: Sailing at maximum speed is a game-changer. Position your boat in a way that allows you to maintain top speed throughout the race. Sometimes, the simplest strategy is the most effective.

- Master the Shifts: Tacking and jibing strategically based on wind shifts is crucial. Upwind, tack when you’re headed away from the mark and sail on the lifts that push you towards it. Downwind, jibe when lifted away from the mark and sail on the headers, guiding you in the right direction.

Sailboat racing tactics are the culmination of strategic planning, meticulous execution, and adaptability to the ever-changing elements. By mastering the art of strategy and tactical maneuvers, sailors can elevate their racing performance.

Ready to Become a Master?

Choose from among American Sailing’s many resources to help you improve your racing — from online courses, to textbooks, to week-long events, you can choose one or all to upgrade your sailing racing skills.

Online Classes

Learn more about how to form winning racing strategies at the Racing Strategy, Tactics and Rules Online Class. This 4-session series hosted by Bill Gladstone starts October 17, 2023.

The most complete books on modern racing tactics and trim, North U takes you all the way around the course. These textbooks are an essential part of any racing sailors library.

Performance Race Week

At American Sailing Performance Race Weeks powered by North U, we spend five days exploring every facet of racing success through an enriching blend of practical on-water training and races complemented by shoreside seminars and insightful video reviews. With a coach on every boat, you’ll receive close personal attention to build on your strengths and eliminate your weaknesses. Join us for this unique opportunity to become a better, more versatile, and more accomplished sailor.

Related Posts:

- Learn To Sail

- Mobile Apps

- Online Courses

- Upcoming Courses

- Sailor Resources

- ASA Log Book

- Bite Sized Lessons

- Knots Made Easy

- Catamaran Challenge

- Sailing Vacations

- Sailing Cruises

- Charter Resources

- International Proficiency Certificate

- Find A Charter

- All Articles

- Sailing Tips

- Sailing Terms

- Destinations

- Environmental

- Initiatives

- Instructor Resources

- Become An Instructor

- Become An ASA School

- Member / Instructor Login

- Affiliate Login

Yachting World

- Digital Edition

How to pick the best downwind sail

- Rachael Sprot

- August 17, 2022

How to set up your boat for smooth, stress-free downwind sailing and how to pick the best downwind sail: Rachael Sprot examines the options

For the coastal sailor, upwind sailing skills are critical: there’s nothing like a lee shore to focus the mind on tacking angles and leeway. For the ocean sailor the challenges are VMG, handling swell and avoiding a crash gybe, but ongoing developments in hull, rig, sail and hardware design have generated huge variations in how we do this. There’s a confusing array of kit and tactics to choose from, so it’s important to spend time on research before spending money on equipment to ensure you get the best downwind sail and setup for your needs.

The first rule of any big decision is to know yourself, your boat and your crew. Neil Mackley, of North Sails, explains: “The thing I most enjoy is sitting down with people and finding out about them. Are they comfortable handling a pole? Are they happy working on the foredeck or would they prefer to manage things from the cockpit? How much stowage space do they have?”

When it comes to the boat, one of the most important metrics is the efficient downwind sailing angle. Broadly speaking, light, flat-bottomed, modern yachts will sail much faster on a reach than on a run. Comparing the new Swan 48 with its predecessors illustrates these changes: the current model is 14% faster on a heading of 120° TWA than 150° TWA. The previous generations only have a 7% difference.

A spinnaker is an essential part of many tradewind cruisers’ sail wardrobe. Photo: Tor Johnson

Scrutiny of the polars for the 1995 Frers Hallberg-Rassy 46 gives a similar picture. When flying a spinnaker in 14 knots it makes 7.1 knots on a TWA of 165° and 8.4 knots on a TWA of 120°. The extra 1.3 knots accumulate to a 400-500-mile gain over a transatlantic passage , but the 45° difference in angle will cost far more in extra distance.

Heavy-displacement, traditional cruisers won’t make exponential gains by reaching. “Wherever possible I run the data through a velocity prediction program to find out where the sweet spot is,” Mackley says, “and for most cruising boats it pays to sail deep.”

Another consideration is how much you’re prepared to use the engine. The east-west transatlantic route is often light airs to begin with and reliable 20-knot tradewinds building through the passage. If the tradewinds are well south, do you carry enough fuel to motor to find them? Weight is a vicious circle: the heavier the boat the slower it is in light airs… To break the cycle you need a sail which can get you moving in under 10 knots of wind, but that may be a specialised sail with a narrow window of operation.

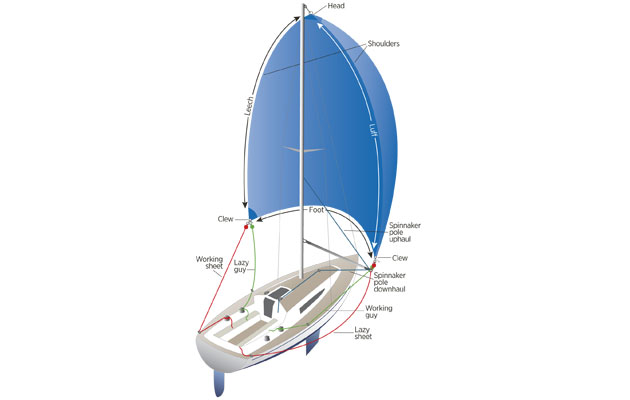

Symmetric spinnakers

“For a transatlantic crossing from Europe to the Caribbean where there’s a high proportion of deep angles, it’s hard to beat a symmetric spinnaker,” says Peter Kay of OneSails. Symmetric spinnakers are the traditional solution to running and they’re still a truly effective option. The pole brings the sail area out from behind the mainsail enabling wind angles of 165° or more.

Weather guru Chris Tibbs flying a symmetric spinnaker on an Atlantic crossing. Photo: Paul Wyeth

There are significant drawbacks, though. The pole work is labour intensive and tiring for a small crew. A 60ft boat flying a symmetric kite will need almost 200m of line for the pairs of sheets and guys. Add in an uphaul and downhaul and there’s a lot going on in the cockpit.

Reaching performance is limited. Although you can set the pole well forwards, you’ll normally need a jockey pole to push the guy clear of the shrouds and stanchions and a running sail will be cut too deep to work well on a reach.

“Although the spinnaker is one of the best tools for a transatlantic, most people don’t go for them because once you’ve arrived on the other side they’re less versatile,” Kay continues. Andy Tarboton of Elvstrom agrees, pointing out that a spinnaker’s broad shoulders puts “more sail high in the sky, which can exacerbate rolling”.

Asymmetrics are usually flown from a bowsprit or the bow roller. Photo: Jean-Marie Liot

Asymmetric spinnakers

Removing the complexity of the pole, an asymmetric spinnaker is flown on a short sprit or the bow roller. Also known as gennakers and cruising chutes, there’s a huge array of asymmetric spinnakers on the market, with an equally confusing array of names. “Asymmetric describes a whole range of styles and performance envelopes,” explains Kay, “from something trying to be a genoa right through to something trying to be a spinnaker.” They all have one major advantage though, which is the ease of sail handling, making them the obvious choice for short-handed crews.

A running asymmetric can be designed to achieve very broad wind angles, almost comparable with those of a symmetric spinnaker. The luff of a running sail will rotate around the forestay as the sheet’s eased, giving wind angles approaching 165° TWA.

If you want to be able to furl the sail though, you’ll need something which is flatter cut and more of a reacher. “Realistically, you’re limited to angles of about 135-145° for sails on furlers, depending on sea state,” explains Mackley, “and then you’re covering a lot of extra distance.”

Oxley parasailers maintain their own shape without the need for a pole.

Parasailers

A sail which attempts to solve the compromise between reaching and running is the parasailer. It looks like a symmetric spinnaker with a pressure relief valve, but the mechanics behind it are very different. A large panel is removed from the upper part of the sail and a paraglider-style wing is suspended in its place. According to designer of Oxley sails, Ralf Grösel, this does several things: it creates lift, it gives the sail structure (similar to a soft batten), and it dampens the rolling motion that conventional spinnakers can generate deep downwind. The opening also acts as a vent, taking the bite out of gusts.

The wing lends structural support to the overall shape so you don’t need a pole. A parasailer can be flown in front of the boat like a symmetric or from the bow like an asymmetric.

There are two control lines on each clew: one running aft to stop the sail pulling forwards, and one running down to midships to counteract the lifting action of the wing. Ideally it is used without the mainsail as the wing performs better in an uninterrupted airflow. This will also help to keep the helm light.

A wing sail is quite an investment and will probably cost more than a single sail, but they should work for a wide range of wind strengths and sailing angles. “It’s like you’re getting two sails in one; a reacher and a downwind spinnaker,” says Grösel.

Handling-wise, a parasailer is a sheep in wolf’s clothing and, other than price, its main detraction is that it won’t deliver as much raw power as a standard kite. If you’re looking for something forgiving, it’s a serious contender.

A double tradewind sail is flown goosewinged but set on a furler. Photo: Shahid Hamid

Tradewind sails

Another slightly left-field option is the loose-luffed, double headsail, such as North Sails’ TradeWind sail, or Elvstrom’s Bluewater runner. Made from stretchy nylon like a spinnaker, but cut more like a large genoa, the pair of free-flying headsails are set on a furler making them easy to douse. They’re designed to be flown in a goose-wing configuration, with the windward sail set on a pole and the leeward one flying off the end of the boom.

It’s ideal for trundling down the rhumbline – known as the 180 freeway, says Mackley. “The rig is much more balanced. When you’ve got a mainsail and headsail up the forces are acting on the boat in different places. With the TradeWind sail you’re being towed from the stemhead.”

Article continues below…

Downwind developments: The latest offwind sails for faster tradewind crossings

These can transform cruising yachts, giving them sufficient power to sail in light airs when previously crews would have been…

How to sail the ARC: Chris Tibbs on how to cross the Atlantic downwind

Meteorologist Chris Tibbs offers some pointers on downwind sailing...

After arriving, you can link the tacks together to create a single sail for light airs’ reaching up to about 100° TWA. The drawback is they’re not suitable for confined waters and are more costly because of the necessary furling equipment, and the fact there are two sails instead of one. The furler could be shared with a Code sail, however. Being made from lightweight polyester they are also no more squall-proof than a spinnaker.

A poled-out headsail is consistently rated the most stable and stress-free downwind rig by ARC crews. It has a wide angle of effectiveness, from a dead run up to about 140°. From a safety perspective it’s a forgiving configuration: if you round up the headsail simply backs, which can be remedied by bearing away again. Dacron can cope with most weather that the Atlantic can throw at you so you won’t feel quite as vulnerable to squalls.

Most headsails can be poled out, though you want to keep the sail flat to reduce flogging in swell so a large genoa might have to remain partially furled. The key is to keep the pole and the sail independent of one another by giving the pole a guy which is separate to the headsail sheet.

Poled out headsails, whether in combination with the mainsail on the other side or another headsail, are rated as the most stable of downwind rigs. Photo: TimBisMedia

The headsail sheet needs leading to the end of the pole and routing aft. A snatch block attached with a strop or soft shackle to the beak works well. The sheet lead will be longer than normal so you might need to use a spinnaker sheet instead of your standard headsail sheets. Depending on the height of the clew, this can be hard to reach once the sail is up or furled, so needs planning.

Once the pole is braced into position, it’s a case of unfurling the sail to leeward, heading on a deep run and gybing the headsail across to the pole, being careful to quickly take up tension on the new sheet to prevent the sail from wrapping around the forestay. Position the pole at clew height and flatten the sail as much as possible.

To furl the sail, ease the sheet and furl it or, to reduce the load on the furler, gybe it across to leeward and furl it behind the main. Because it’s independently set, the pole can be left in position while the sail is furled if you need to manoeuvre or ride out a squall. Once the wind exceeds 18-20 knots most cruising boats will make good speed under this configuration.

Sailing wing on wing on the Oyster 575 Angels’ Share. Photo: TimBisMedia

Another variation for vessels with twin grooves in the forestay foil is to set two headsails and no mainsail. One can be set on the pole and a second sheeted to the end of the boom, which needs to be braced out using the preventer. It’s a bit of a performance to rig and de-rig, but once up it’s a stable rig which works from broad reach to broad reach. Since there’s no work involved in gybing, it could be a great short-handed solution.

Although not technically downwind sails, Code sails are free flying headsails for close reaching in light airs. They do a similar job to a big genoa so are useful on yachts with fractional rigs and small foretriangles, and are popular on multihulls. There is a place for them when cruising, especially if you’re keen not to resort to the engine when the wind is light. For example, OneSails’ Flat Furling Reacher or FFR is a cross between a Code 0 and a genoa, with a range of 50-130°. It fills in the gap between a headsail and a deep running asymmetric so is a useful addition to the sail wardrobe but is unlikely to play a big role in a tradewind crossing.

A big light airs sail for a big boat: a Jeanneau Yacht 60 reaching under code sail. Photo: Gilles Martin-Raget

Headsail handling: Furlers

Spinnaker handling has been revolutionised by furlers, allowing the sail to be doused from the cockpit. Continuous line furling technology has developed across from Code 0s but with one key difference, spinnakers are better furled from the top and not the bottom. On a Code 0-style furler the tack is fixed to the furling drum, on a top-down furler the tack is free to swivel.

The furling motion on a top-down furler is transferred to the head of the sail via a heavy duty anti-torsion cable. Furling a spinnaker this way is much more effective as the sail cloth locks down on itself making it less prone to spilling open.

The OneSails Integrated Furling Structure sail uses continuous fibre technology to replace the anti-torsion cable. Photo: OneSails

There are also reaching spinnakers with luff cables built into the sail, and more recently, ‘cableless’ furling sails which have a structured luff using laminate technology, micro-cables woven into the sail or soft luff cords. Removing the anti-torsion cable saves weight and makes the sail easier to handle, but it might not furl so well in sub-optimal conditions. The systems with a torsion cable will probably cope better when you’re caught off guard.

The advantages of a furling spinnaker for short-handed crews are obvious. Not only do they make a single-handed spinnaker douse from the cockpit possible but they also reduce the volume of the sail, making it easier to stow.

However, there are drawbacks. Most furling sails will be too flat to perform well on deep angles. Sails with an external luff cable will do better than those with inbuilt cables because they’ll be able to project around the forestay more, but you still can’t have a proper, broad-shouldered runner on a furler.

It’s tempting to leave a furled spinnaker up to sit out a squall, but that’s not recommended: even ‘locking’ furlers are not totally reliable. If you do decide to leave one up, Neil Mackley suggests using a soft shackle or carabiner to secure the drum. Be aware that most spinnakers also won’t have UV protection.

Spinnakers are easiest to douse top down with a snuffer. Photo: Richard Langdon

Headsail handling: Snuffers

Getting a spinnaker down is always the hardest part of the process. Snuffers have been around since the 1980s when French designer Etienne Giroire refined the DIY socks which solo sailors such as Eric Taberly were using.

Giroire realised that the lines for raising and lowering the sock needed to be contained within a separate sleeve to prevent them from tangling with the sail. He also noted that the two control lines had very different jobs: the line for pulling the sock up can be light weight because once the sail starts to fill, the snuffer practically raises itself. The line for pulling the sock down needs to be strong and of twist-free construction. He went on to found ATN, which has sold over 30,000 snuffers. The oval plastic mouth has been replaced by a canvas hoop for larger yachts, while some manufacturers now offer inflatable rings to make stowage easier. Other than that, the design has changed little over the years.

The one drawback is that they require someone on the foredeck to heave down on the sleeve, which can be hard work in high winds. A ratchet block on the deck gives a bit more control over the down line. Bearing away and sheeting in will blanket the sail, and – if that still isn’t enough – you can blow the tack and the sail will flag behind the main.

Snuffers can be retrofitted to most sails including big symmetrics. They are a bit less elegant than furlers, but much more economical and a bit less tricksy.

No system is foolproof, and both snuffers and furlers can fail. If they do, you need to be able to drop the spinnaker conventionally. Make sure that you’re all clear on how you would do it on your boat.

Regular rig inspections are essential on downwind passages. Photo: Tor Johnson

When it comes to downwind sailing, the only thing most people can agree on is that a poled-out headsail is the bread and butter. What you choose to add on top of that is up to you and will depend on variables such as budget, crew, boat, and other cruising plans. Even with a perfect sail set-up, sea state can make it impossible to hold an optimum course – as last year’s ARC participants found when a nasty cross swell developed.

Very few sails can deliver both reaching and running functions, apart from the parasailer and ‘tradewind’ sail, neither of which are high-performance options.

Elvstrom’s Andy Tarboton notes that the most common choice for people taking a single sail is somewhere in the middle ground, such as a mediumweight asymmetric. Peter Kay at OneSails would choose a deep running asymmetric spinnaker, if he could only have one, and a FFR (Flat Furling Reacher) if he could have two. North Sails’ Neil Mackley was drawn to the symmetric spinnaker: “It’s a very efficient sail downwind, but because of the pole it’s a hard one to have in the inventory.” The tradewind and a Code sail would be a versatile combination for more conservative cruising.

Understanding the sail’s capabilities and your own limitations will make for efficient sailing. Work out where your priorities lie on a scale of fun to comfort and ask an experienced sailmaker to narrow down the options.

If you enjoyed this….

Yachting World is the world’s leading magazine for bluewater cruisers and offshore sailors. Every month we have inspirational adventures and practical features to help you realise your sailing dreams. Build your knowledge with a subscription delivered to your door. See our latest offers and save at least 30% off the cover price.

Yachting Monthly

- Digital edition

Which is the best way to sail downwind?

- Chris Beeson

- August 12, 2015

Poled-out genoa, spinnaker or cruising chute? Chris Beeson finds out which to use to sail downwind, when and why

Which, of the poled-out genoa, spinnaker and cruising chute boats, offers the best way downwind for you? Credit: Colin Work

Downwind cruising can offer some of the most relaxing sailing of the season. Just ease the mainsheet, pole out the genoa, engage autopilot, mix a drink and let the miles tick away as a cooling breeze rolls across the transom. However, with all that time on your hands, the mind can start to wander.

You might start wondering, if progress is a little slow, whether you would be better off digging the spinnaker out of its home in the forepeak? Would the bothersome cat’s cradle involved in putting it up and the tricky business of gybing, potentially perilous for a couple, pay off in time saved? Or would rolling make life too uncomfortable? Perhaps you have a cruising chute? Would sailing the angles downwind be quicker than a spinnaker running dead downwind, even if it does involve more activity? If you stick with your poled-out genoa, how much longer, if at all, will the trip take?

These are questions that any cruising sailor might ask, but what is the answer? The likelihood of a boat identical to yours sliding past with a different downwind set-up, offering a direct comparison, is seriously remote, and two identical boats with two different set-ups: all but impossible.

How do we find out?

We spoke to Sunsail, which very kindly agreed to loan us three identical Beneteau F40s from its racing fleet in Port Solent. Each boat would be crewed by two, with a third onboard to take pictures and make notes.

Each boat would fly a different downwind rig and sail in the same wind on the same day to settle the issue. The criteria used to select the best downwind rig were speed, comfort and hassle.

The plan was to check wind direction on the day and set a distant waypoint dead downwind. The boats would start in a line, and the distance to waypoint was noted. After sailing downwind for a set period, the distance to waypoint would be noted again to measure how far down the track the boats had got.

On the day, the wind was forecast to back from NW to W, and remain quite light at around 5-10 knots. With a knot of ebb tide under us, the apparent wind would reduce still further. It was also a baking hot day so a sea breeze looked certain to back the little wind we had even more. The upshot was that we noted our start position, our finish position and any course changes, and simply sailed downwind until the answer became obvious.

How to avoid the spinnaker death roll

You can reduce roll but if you find yourself in this situation, just release the spinnaker halyard

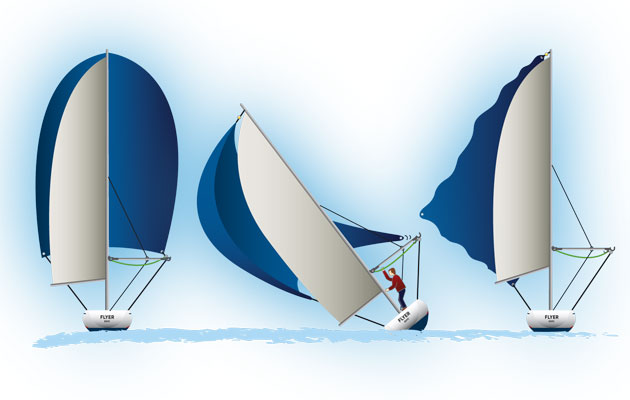

The main peril of sailing downwind in a breeze is rolling. It may start gently but within seconds you can be rolling from rail to rail and a moment later she rolls too far, the rudder loses grip and the boat lays down beam on under a tattoo of angry nylon.

There are a few key ingredients to rolling. Conditions may be gusty, and there’ll likely be too much wind for the sail, which you should have dropped by now. Waves are probably a factor too. If there is too much twist in the main, a side force is generated at the top of the mast that can begin the roll. As she rolls, the spinnaker rolls from side to side and its centre of effort moves much further outboard, exacerbating the situation.

You can always head up a point or two, away from dead downwind, to reduce roll, but if you need to head dead downwind, you can control the situation by using plenty of vang to flatten the mainsail’s leech.

To stop the spinnaker rolling about, ease the pole forward a touch to move its centre of effort closer the centreline, and strap it down by lowering the pole and hauling the tweakers, or ‘twings’, down to deck level, effectively moving the spinnaker sheet’s ‘car’ position forward.

If you do find yourself in the dramatic final act of a death roll, beam on and going sideways with the rail under, just release the spinnaker halyard (this is why it’s important to make sure halyards are always flaked properly). The boat will pop upright and you can start recovering the spinnaker you should have dropped earlier. Clever cruisers will drop the spinnaker early if the wind builds.

Without a snuffer, a pre-rigged tack release line should defuse the situation quickly

If you have a snuffer to tame a spinnaker, great. If you don’t, before you hoist, rig a quick release line from the inboard end of the pole to the guy’s snap shackle. Pull it and the tack releases, leaving the sail to flap in the main’s lee. Just haul in using the lazy guy or sheet.

Before you hoist, rig a quick release line from the inboard end of the pole to the guy’s snap shackle

Poled-out genoa

A poled-out genoa is many sailors’ preference for sailing downwind and needs no additional canvas

In many ways this is the default set-up. Most yachts already have a mainsail and a genoa or jib, and if there’s enough breeze, the boat goosewings downwind with the main on one side and the genoa on the other. No extra kit or expense involved, so it’s perfect! Or is it?

The problem with goosewinging is that it’s a fragile set-up. If winds are light, the jib will collapse on the centreline and slat about. This is both slow and expensive, as slatting damages sails. If there is enough breeze to fill the sail, it has lots of depth but what you need is area – a flat sail to catch as much breeze as possible. If there’s plenty of wind but its direction isn’t absolutely stable, or the boat is rolling, again the jib collapses but this time refills with a rig-shaking crack.

The solution is to push the genoa’s clew out so that the foresail is flat and ideally perpendicular to the wind. The sail catches maximum breeze and it can’t collapse. If you’re goose-winging, try prodding the genoa’s clew out with an extended telescopic boathook – see how the sail area increases.

How to set up

There are some in the Yachting Monthly office who have simply stuffed a boathook into the clew and lashed the inboard end to the shroud. Crude perhaps, but it can be effective.

The recommended options are either a whisker pole, usually light weight and telescopic to some extent, or a spinnaker pole. Both attach to the mast inboard and a sheet outboard, up- and downhauls and, ideally, an afterguy to stabilise the pole.

As our Sunsail F40 had a spinnaker pole, we set that up. We decided not to clip the outboard end to a genoa sheet as it hampers any emergency manoeuvre – you can’t tack with a pole on the sheet.

Instead we tied a third sheet, or afterguy, to the clew, ran it back through the pole end (a block lashed to the pole end would chafe less) to a block on the aft quarter, which gave us a better sheeting angle than the genoa sheet cars allowed. This gave the pole three-point stability, and if we needed to head upwind in a hurry, to recover a man overboard perhaps, the sheet could just be cast off and the pole left in place, leaving us in full control of the genoa.

As the wind builds, the unique advantage of this set-up is that you can reef the genoa to reduce sail area. The mainsail will long since have been dropped but you can sail on under headsail alone, taking in a few more rolls as required.

This involves a trip forward. We tripped the pole from its port gybe and lowered the outboard end onto the foredeck. Then the third sheet was unreeved, leaving the boat conventionally goosewinged, led through the pole end and back outside the lifelines to the block on the other aft toerail and onto the primary winch. Hoist the pole on the opposite side, gybe the main, haul in on the afterguy, then adjust the pole’s lines until it’s stabilised. All in all, gybing took about five minutes.

1 With a third sheet already bent onto the genoa clew, Mark prepares the pole for port gybe

2 The third sheet is through the pole end, uphaul and downhaul are rigged, ready for launch

3 With the pole height set, Mark hauls on the third sheet to unfurl the genoa

How did it go?

We had our spinnaker pole already rigged with the inboard end slotted into the mast cup and the outboard end resting on the pulpit. That was easy, no-nonsense prep. With the afterguy clipped into the end of the pole for a port gybe set, we hauled it and unfurled the genoa until the pole end reached the clew, then strapped the pole down using up- and downhaul and afterguy.

There’s not enough wind to fill the sail but it’s set and ready to catch the slightest zephyr

We were off. Well, sort of – we made 3.3 knots over the ground with the wind 3.1 knots apparent. Our problem was, squared right off, we were not generating any apparent wind, or so little as to make no difference. We had only a minimal feel of steerage, but we retained full control and held a good course dead downwind.

The cruising chute boat sails shallow angles in light airs, so progress is slow

At first we made ground over the asymmetric boat by holding a straight course: she had been 50 yards ahead, but by the time she came back on port gybe she was 50 yards astern of us.

Meanwhile the spinnaker boat pulls well clear and sails deeper angles

Then the wind backed 45 degrees, freshened a touch, and had us sailing east instead of south-east, our advantage evaporated and even though our speed over the ground went up to 5.1 knots, the asymmetric boat was 200 yards ahead of us and the symmetric boat remained a quarter of a mile ahead.

Gybing was a controlled business, not a tremendous ordeal for two, and would have been quicker if we hadn’t rigged the afterguy, but it was the seamanlike thing to do. That aside, we could happily have switched on the autopilot and watched the world go by.

This was only slightly more involved than furling a genoa. We released the afterguy, hauled on the furling line and that was that. Then the only thing left to do was to ease the pole uphaul, unreeve the afterguy and lower the inboard end of the pole.

Symmetric spinnaker

The spinnaker is almost three times the size of the genoa, and it showed in speed

A symmetrical spinnaker is used as both an aerodynamic sail when reaching, with air flowing across it like a foil and creating lift, and also as a windjammer, simply blocking the wind when heading deeper and dead downwind.

There are some issues when using it. In light winds even the slightest gust can accelerate the boat so that she sails through her apparent wind, leaving the spinnaker drooping lifelessly. In these conditions the best option is to head onto a broad reach, so apparent wind, and therefore boatspeed, will be higher. The only problem then is the need to gybe.

Another issue with heading dead downwind under spinnaker is that increases in wind strength can go unheeded. The boat speeds up and everyone has a jolly time, but if there’s a sea running and the boat begins to roll, things can go wrong very quickly. By that point, there’s often enough wind to make going forward to drop the spinnaker an edgy business.

Setting up for spinnaker sailing

This can be a lengthy business for a couple. First, sheets and guys need to be correctly rigged. As well as needing turning blocks in all the right places and the lines themselves, you need to rig the sheets and guys correctly because the loads involved in flying a sail of that size tend to make a big deal of any mistakes. You also need to know that the spinnaker has been packed free of twists, and that the corners you believe to be the clews and the head are indeed just that. Check all this before setting off as it’s easier on a stable boat than at sea.

The next step is to hoist the pole, then the spinnaker. It’s quite a hassle for a crew of two. Ideally, the helmsman would head dead downwind and flip on the autopilot just before the hoist, then move forward in the cockpit.

The foredeck crew hoists the halyard at the mast and the spinnaker goes up sheltered by the mainsail, while the cockpit crew looks after the halyard tail, sheets and guy. It’s much easier if you have a snuffer as the sail would be hoisted to the masthead before it was opened, so you can check everything is as it should be before filling the sail, and, with the halyard hoisted, there’s one less line to look after.

1 There’s a lot of setting up to do and, with a sail of this size, it needs to be right

2 Even if the sail had a snuffer, there’s a lot for two people to do during a spinnaker hoist

3 With the spinnaker hoisted and pole squared back, progress is quick and leisurely

Launch the pole on the new gybe and set it at the right height by hauling on the uphaul

The foredeck crew goes forward and the helm runs dead downwind and flips on the autopilot. With both sheets hauled tight and cleated off, the foredeck crew grabs the lazy guy – the helm needs to make sure there’s enough slack in the guy to do this – then trips the pole off the working guy. The helm lowers the pole uphaul so that the foredeck crew can load the new guy, then the helm hauls the pole up on the new gybe and hauls in on the guy, releasing the old sheet and trimming the new one. In benign conditions it’s a relatively straightforward job for the foredeck crew but the helm has five different lines to control in synchrony with the foredeck crew. Get the choreography wrong with a sail of this size in any but the lightest winds and the results can be expensive.

The symmetric spinnaker lets you sail deep downwind, but can be a handful for a short-handed crew

Sailing as a couple, you need a very slick routine to fly and gybe a spinnaker with confidence. The biggest problem is the sheer number of lines required. With a sheet and guy each side you quickly run out of winches, especially if you’re hoisting or dropping the spinnaker behind the jib, as that needs a winch too. Then there’s the need for the spinnaker sheet to ideally be taken across the boat to the opposite halyard winch, so that the trimmer can see the sail. At one point we ended up with two sheets criss-crossing the cockpit!

Two sheets, two guys, uphaul, downhaul and halyard tail – it’s a lot of extra rope

Had we not been intending to practice a few gybes, we could have got away with sheets alone. In these winds we could have hauled the twings, or sheet barberhaulers, down to the deck to create a new guy after gybing but in anything stronger, twings probably aren’t up to the loads of a guy.

Once flying, a symmetric spinnaker is fairly simple to control downwind, provided you don’t head so deep that the spinnaker backfills as you sail through the apparent wind, and wraps around the forestay.

We used the ‘letterbox’ method to drop the spinnaker. It’s the easiest way to drop but you do need a loose-footed main. Feed the lazy guy between the main and boom and get the halyard ready to drop. Ease the pole right forward, give the halyard a turn or two on a winch, hand the tail to the helm, stand in the companionway, release the halyard clutch and start hauling on the lazy guy. The helm eases the halyard enough for the crew to haul the sail in, but not so much that it touches the water.

Cruising chute

With four lines and no pole, a cruising chute is the simplest downwind sail

A cruising chute, also known as an asymmetric spinnaker, is one that has its tack and clew at different heights. The sail flies from a bowsprit, projecting the sail’s tack beyond the pulpit so that its foot doesn’t foul. As its tack is on the centerline, sailing dead downwind isn’t ideal because the main pretty much blankets the entire sail.

This Sadler 29 demonstrates that you can go dead downwind with a cruising chute: goosewing

A goosewinged asymmetric can run dead downwind but we decided to use it for the purpose it was designed: sailing the angles. It was a decision forced on us somewhat by the light winds, meaning that the apparent wind often died away when heading dead downwind, collapsing the sail. Sailing the angles gave us more apparent wind, and so more speed.

We were inside-gybing, with the dotted sheet, so the clew passed between the chute luff and the forestay. Rig the solid sheet for an outside gybe

The tackline is pulled tight, halyard and sheets are bent on: it’s ready to hoist

We had no bowsprit and the bow roller didn’t project beyond the pulpit so we strapped the spinnaker pole into the bow roller and lashed a block to the end of the pole. We would run the sail’s tackline through this block and lead it back to a halyard winch. We didn’t want to use the pole-end fitting because it wasn’t designed for the perpendicular loadpath the tackline would impose. This arrangement allowed us to project the tack beyond the pulpit. Sheets were run outside the lifelines to blocks on the quarters and back to the primary winches.

The beauty of gybing an asymmetric is that it can all be done from the cockpit. There are two ways to gybe an asymmetric: inside (between the luff and the forestay) and outside (outside of both). The latter works well in all but the lightest winds but often, during gybes, the old sheet ends up sliding down the luff and under the bow. That’s why you see asymmetric racing boats with bits of sail batten taped to their bowsprit, or ‘horns’ on the tack: to snag the lazy sheet. That’s not a problem with inside gybing but there is a chance the sail will wrap around the forestay during the gybe if your technique isn’t slick. We opted to inside gybe and from sailing on one gybe to sailing on the other took 10-15 seconds.

With the sailbag clipped to the lifelines, the tackline was attached, sheets run, then the halyard was clipped on. The tackline was hauled in to get the tack over the pulpit to the tackline’s block, and the sheet was loaded on the winch and self-tailer with plenty of slack.

Running almost dead downwind we hoisted the sail easily. With the halyard clutch closed, we came up onto a broad reach, the sail filled and we trimmed on.

Heading too deep, we sailed through our apparent wind and the sail hung limp

The plan had been to broad reach at about 150° to the apparent wind and flip on the autopilot. However, the pressure was so patchy that the apparent wind was constantly shifting, coming forward onto the beam as we accelerated and aft as we slowed. Hand-steering was necessary.

By sailing further, the chute boat found little pockets of wind and was soon charging

After a laboured first gybe, our technique improved rapidly. As the boat heads down, the old sheet is eased until the clew is just forward of the forestay, then the new one is hauled in. Steer dead downwind until the clew is round the forestay. Watch the clew or mark the sheets so that you know when you’ve eased enough.

Gybing takes about ten seconds and can be done from the cockpit

As the new sheet is hauled in, come through the wind, bring the main over and come up to fill the sail. In these light winds we gybed by hauling the falls of mainsheet across. In stronger wind, goosewing while sheeting the main onto the centreline before gybing.

We headed dead downwind so that the main blanketed the sail. If we had a sock, we would just release the sheet and snuff the sail from the foredeck then release the tackline. With no sock, we gave the spinnaker halyard one or two turns on a winch to stop the sail falling into the water, passed the tail to the helm, released the clutch, hauled down the sail, unclipped the running rigging and bagged the sail.

If your mainsail isn’t loose-footed, don’t haul in the chute under the boom as there’s certain to be a loose split pin that will tear the sail. Sit on the sidedeck, haul the chute into your lap, then feed it down the hatch.

So, which is the best way to sail downwind?

FASTEST: spinnaker

The spinnaker boat was undoubtedly the quickest but the cruising chute was a close second

It’s no surprise that this went in order of sail area. The spinnaker (128m2/1,378sq ft) is almost 30% bigger than the cruising chute (93m2/1,001sq ft) and over three times the size of the genoa (37m2/398sq ft). The spinnaker was quickest at every stage – but not by a distance proportionate to sail area.

The poled-out genoa boat was only 7% slower after 90 minutes’ sailing

After 7.1 miles of sailing, the spinnaker was about 400m, or 0.2 miles, ahead of the poled-out genoa, only 3% faster, with the cruising chute just a few metres behind the spinnaker. It was closer than expected but if speed is your priority and you know what you’re doing, choose the spinnaker.

In light winds, the spinnaker and cruising chute boats had to sail the angles to create some apparent wind and fill the sail. The poled-out genoa, though much smaller, was ready to catch the slightest zephyr, and sailed the shortest distance.

The cruising chute boat sailed furthest, gybing eight times to the spinnaker’s three and the genoa’s two. However, on one of our gybes, we found a patch of wind and accelerated away while the spinnaker and genoa boats were stalled. In these conditions, sailing further meant we could find some little patches of wind that the others didn’t.

MOST COMFORTABLE: poled-out genoa

If the breeze gets up, reefing the genoa is a piece of cake, not so the other sails

We got none of the rolling that can turn a downwind passage into something of a fairground ride. In a stronger breeze, the genoa boat will roll least because the sails’ centre of effort is lower. In heavier weather, when you’re running under poled-out headsail alone, you can reduce sail area by furling. It’s the only strong-wind option of the three for shorthanded cruising.

Running in light winds the poled-out genoa is always set, whereas the spinnaker hangs, risking a twist

The spinnaker’s centre of effort is higher so it rolls most in stronger winds. There are techniques to limit it and avoid the ‘death roll’ but take them early because once she starts rolling, doing anything except hanging on isn’t easy.

By sailing the angles the cruising chute boat avoids the entire issue of roll as heel will be constant. Speed, and therefore apparent wind, is highest of the three set-ups too. In stronger winds broaching is possible if the boat heels so far that the rudder stalls. In stronger breeze, the greater sail area is a liability.

LEAST HASSLE: Cruising chute

With no pole, it’s easier to manoeuvre quickly and visibility forward is better than the poled-out genoa

Just one sheet to handle instead of six lines for a spinnaker, quick to gybe and no need to go forward

The spinnaker crew was the most hassled. The pole needed rigging, sheets and guys running, and there are lots of little details to get right. We dip-pole gybed but even end-to-end gybes require a spell forward as well as having someone to work the cockpit. The genoa boat had a relaxed time in between gybes, but again, any gybe involves a trip forward and someone choreographing in the cockpit. Gybing a pole is a hassle, regardless of what’s on the end of it.

Even in light airs, helm and trimmer must be on the ball – fine if you like sailing a boat rather than riding it

The cruising chute boat gybed in seconds without a trip forward. In lighter winds it makes more demands on the helmsman and crew, trimming and changing course to keep the sail filled downwind, but if you enjoy sailing boats rather than riding them, activity on the cruising chute boat is constant but never demanding. On the other boats there’s less to do, except during gybes when there’s too much for two. Visibility forward is decent so, for manoeuvrability in crowded waters, this and its gybing speed give it the edge.

The yacht designer’s view

Luke Shingledecker, Farr Yacht Design

We spoke to Luke Shingledecker of Farr Yacht Design, the company that designed the Beneteau First 40

‘The best progress downwind is often achieved by sailing the angles because the apparent wind speed is greater, and the apparent wind angle is closer to a reach, where the sails can generate lift and are more efficient. Dead downwind, the sails just catch wind. Sailing higher increases boatspeed enough to overcome the extra distance sailed.

‘In stronger winds, the loss of apparent wind speed is a much smaller portion of the total windspeed so the best progress downwind occurs at deeper angles.

‘Dead downwind, increasing sail area by switching from poled-out jib to spinnaker increases thrust, which increases boatspeed. But increased boatspeed decreases the apparent wind speed, which means less thrust. So, as you found, the increase in boatspeed is much smaller than the increase in area. Also, the thrust required to increase speed is not proportional; at typical boatspeeds, the required thrust increases with the third power of speed (30% more thrust to go 10% faster).

‘Reviewing our velocity prediction for this boat, I would expect the increase in boatspeed (from poled-out jib to symmetric spinnaker) to be 10-12% in 5-10 knots of wind, decreasing to 7% in 15-20 knots of wind – a bit more than you have recorded, possibly due to the difficulty of keeping the spinnaker full. The relative speed differences should reduce in stronger winds.’

Medina Yard, Cowes

To Craig Nutter for his help on the day. A veteran of two America’s Cups and a Whitbread Race, Craig is now manager of the Medina Yard in Cowes and a good friend of YM.

Tel: 01983 203872

Email: [email protected]

Web: www.medinayard.co.uk

To Sunsail for loaning us three F40s. Sunsail is an approved RYA Training Centre offering a comprehensive range of RYA theory and practical courses, from Start Yacht to Yachtmaster, and race training courses, including spinnaker handling. Friendly, experienced instructors can even provide one-on-one training on your own yacht.

Tel: 02392 222221

Email: [email protected]

Web: www.sunsail.co.uk

Points of Sail Diagram: A Visual Guide to Sailing Positions

by Emma Sullivan | Jul 16, 2023 | Sailboat Racing

Short answer points of sail diagram:

A points of sail diagram illustrates the different angles at which a sailing boat can interact with the wind. It typically presents five main positions – close-hauled, beam reach, broad reach, running, and an illustration of how these angles relate to the wind direction. These diagrams assist sailors in understanding sail trim and optimal boat performance.

Understanding the Points of Sail Diagram: A Step-by-Step Guide

If you’re new to the world of sailing, understanding the points of sail diagram is essential knowledge. It serves as a compass for sailors, helping them navigate their way through different wind conditions and efficiently maneuver their boats. In this step-by-step guide, we will dive deep into what the points of sail diagram mean and how they can be used to your advantage on the water.

1. Introduction: The Importance of Understanding Points of Sail Sailing is all about harnessing the power of the wind to propel your boat forward. To do this effectively, you need to understand how your sails interact with the wind from different directions. The points of sail diagram provides a visual representation of these angles, serving as a valuable tool to help you optimize your speed and direction while sailing.

2. Breaking down the Diagram The points of sail diagram typically features eight distinct sections or “points” that represent different angles at which the boat can sail in relation to the wind direction. At one extreme is upwind sailing or close-hauled sailing (pointing directly into the wind), followed by various angles such as close reach, beam reach, broad reach, running downwind, and finally dead downwind (with the wind directly behind). Each point on the diagram represents an angle with respect to true or apparent wind.

3. Close-Hauled Sailing: Challenging but Efficient Close-hauled sailing is when you’re pointing directly into the wind or slightly off it. This is considered one of the most challenging points on the diagram but yields excellent efficiency if sailed correctly. Your sails will be trimmed in tightly, allowing them to capture as much energy from head-on winds as possible without stalling.

4. Reaching: Finding Your Sweet Spot When you start moving away from close-hauled sailing, you’ll enter other points called reaches—close reach, beam reach, and broad reach—that offer differing angles between your boat’s bow and the wind direction. Reaching is like finding a sweet spot on the points of sail spectrum, wherein boat speed and maneuverability are maximized. Depending on the angle, you may need to adjust your sail trim and weight distribution to optimize performance.

5. Downwind: Embracing the Wind’s Power As you move farther down the points of sail diagram, you’ll reach running downwind and dead downwind (also known as sailing by the lee). These points have their unique challenges but also immense rewards. Running with the wind directly behind can provide exhilarating speed, but it requires careful handling of your sails due to possible accidental jibing. By understanding these points, you can trim your sails for optimal performance while maintaining control.

6. Practical Applications: Utilizing Points of Sail Diagram to Your Advantage Understanding the points of sail diagram is not only about theory—it has practical implications too. By analyzing factors such as wind strength, sea state, and desired course, you can determine which point on the diagram is most suitable for reaching your destination efficiently. Adjusting your sails accordingly and making slight alterations in your heading based on wind shifts will help you maintain higher speeds and reduce unnecessary zig-zagging.

7. Improving Sailboat Racing Skills with Points of Sail For sailors who engage in competitive racing, comprehending the points of sail diagram becomes even more fundamental to success on the racecourse. Understanding how your boat performs in different angles relative to other boats allows for strategic decision-making during mark roundings and tactical maneuvers throughout a race.

In conclusion, mastering the points of sail diagram is a crucial skill for any sailor looking to improve their efficiency and navigate smoothly through various wind conditions. Whether you’re a novice sailor or an experienced racer, understanding this visual representation will undoubtedly enhance your ability to harness the power of wind effectively while enjoying what sailing has to offer. Happy sailing!

How to Interpret the Points of Sail Diagram: A Beginner’s FAQ

Title: Exploring the Points of Sail Diagram: A Beginner’s Comprehensive Guide

Introduction: Sailing, with its timeless appeal and serene beauty, has captivated human beings for centuries. It offers an exhilarating way to navigate through vast water bodies using the power of the wind. However, fully understanding the various “points of sail” is crucial for any novice sailor looking to embark on this extraordinary adventure. In this blog post, we aim to demystify the Points of Sail diagram by providing a comprehensive FAQ-style guide that encompasses all necessary details and navigational techniques one needs to grasp before setting sail.

1. What is the Points of Sail Diagram? At its core, the Points of Sail diagram presents a visual representation of all possible angles at which a sailing vessel can harness wind power effectively. It illustrates how a boat’s sails interact with the wind relative to its course and helps sailors determine the most optimal technique for achieving their desired speed and direction.

2. Understanding the Wind Directions: The first step in interpreting this diagram involves understanding four fundamental wind directions:

a) Dead Ahead (Close Hauled): The wind direction aligned directly forward from your boat. b) In Irons: Sailing too closely into the wind, causing your sails to luff or flap irregularly. c) Beam Reach: The wind blowing perpendicular to your vessel’s side. d) Running Before or Downwind: The wind coming from behind your boat.

3. Determining Apparent Wind: Apparent Wind refers to how the actual windspeed and direction impact a boat as it moves through water. Depending on factors such as boat speed and angle relative to true wind, apparent wind may differ slightly from real-world measurements.

4. Identifying Sail Positions and Pointing Angles: The diagram demonstrates six key points where you can position your sails based on their interaction with apparent wind:

a) Close Hauled (AKA Beating or Cracking Off): Sailing as closely into the wind as possible. b) Close Reach: Sailing at an angle just off the wind direction. c) Beam Reach: Sailing perpendicular to the wind, with sails fully open and untrimmed. d) Broad Reach: Sailing slightly downwind while maintaining good speed and stability. e) Running (Downwind Run): Sail positioned for maximum acceleration from a tailwind. f) Wing-and-Wing: A technique used when sailing directly downwind or running, where two sails are set on opposite sides of the boat.

5. Optimal Courses: By understanding which points of sail are best suited for different wind angles, you can plot optimal courses that minimize tacking maneuvers, maintain efficient speeds, and maximize your overall sailing experience.

Conclusion: Mastering the Points of Sail diagram is like unveiling the secrets of the sea—a necessary step on a sailor’s journey towards complete control in harnessing wind power and navigating through vast waterways. With this comprehensive guide, beginners can now confidently interpret and apply the principles illustrated by this invaluable diagram. Enjoy your time exploring these uncharted waters while experiencing the thrill only true sailors understand!

Demystifying the Points of Sail Diagram: Essential Concepts Explained

Title: Demystifying the Points of Sail Diagram: Unlocking Essential Concepts

Introduction:

Sailing, though often seen as an exhilarating and graceful sport, can be quite enigmatic for novices. Aspiring sailors often encounter a perplexing diagram called “The Points of Sail.” While its purpose is evident to seasoned sailors, deciphering this visual aid can leave newcomers scratching their heads. If you find yourself in this group, fear not! We are here to unpack this enigma and provide you with a comprehensive understanding of the essential concepts behind the points of sail diagram.

1. Unveiling the Hidden Navigation Tool:

At first glance, the points of sail diagram might seem like a cluster of incomprehensible arrows and sectors. Yet, beneath its arcane appearance lies one of sailing’s most crucial navigation tools—an instrument that reveals how a sailboat interacts with wind directions in different scenarios.

2. Direction Influences Sailing Efficiency:

To understand the points of sail fully, it is vital to grasp that wind direction plays an influential role in determining sailing efficiency. For instance, trying to sail directly upwind not only becomes challenging but may even render your conquest impossible due to physics constraints.

3. The Big Picture: Dividing Wind Directions:

Divided into eight main divisions delimited by arbitrary angles (known as sectors), the points of sail diagram delineates various wind directions relative to a sailboat’s bow – from dead ahead (wind coming directly towards) through all possible headings until reaching dead astern (wind coming directly from behind).

4. Zones Destined for Thrilling Speed:

Among these sectors lie three significant zones that provide optimal conditions for maximizing speed and efficient navigation—close-hauled (or close to the wind), beam reach, and broad reach zones.

a) Close-Hauled Zone: Taking you closest to sailing against the wind, known as pointing close-hauled or beating into the eye of zephyr, this sector is ideal for gaining height without any side drift.

b) Beam Reach Zone: With wind coming from a ninety-degree angle to the boat, this zone enables smooth sailing with impressive speeds. Be prepared to experience a quick rhythm and exceptional lateral movement.

c) Broad Reach Zone: As you venture away from the close-hauled zone, the wind angle increases further until it reaches your vessel at an acute rearward angle within the broad reach zone. Brace yourself for exhilarating surges of speed combined with rejuvenating breezes brushing against your face.

5. Tacking and Jibing Essentials:

While familiarizing yourself with the points of sail diagram, it is essential to grasp two fundamental maneuvers – tacking and jibing. Tacking involves turning your boat’s bow through the wind while crossing into another close-hauled sector, allowing you to change direction efficiently. Conversely, jibing entails swinging your stern through the wind, facilitating shifts from one broad reach or run sector to another.

6. The Pleasures and Challenges of Dead Zones:

Filling in the gaps between those three key zones lie three areas aptly named dead zones (no-sail sectors). These sectors encompass scenarios where the sailboat struggles due to inadequate winds in relation to its direction—irresistible challenges that demand remarkable skill and patience from sailors determined to conquer them.

Conclusion:

Admittedly, unraveling the intricacies behind a seemingly complicated diagram like “The Points of Sail” might appear daunting at first. However, understanding these essential concepts is crucial for aspiring sailors seeking smooth navigation across varying wind directions. By embracing the intricacies delineated in this blog post, we hope that you embark on your sailing adventure equipped with newfound confidence and knowledge—a blend essential for taking full advantage of every possible point of sail on your nautical journey!

Mastering Sailboat Navigation: Unveiling the Power of the Points of Sail Diagram

Sailboat navigation is an ancient art that mariners have entrusted their lives to for centuries. From early explorers to modern-day sailors, understanding the ins and outs of navigating a sailboat is crucial for a successful voyage. One powerful tool that has stood the test of time is the Points of Sail Diagram – a clever representation that unlocks the true potential of sailing.

The sailboat’s points of sail diagram depicts six different angles at which a boat can effectively sail in relation to the wind. These angles are named: close-hauled, close reach, beam reach, broad reach, running, and dead downwind. Each point represents a unique combination of sail trim and wind direction that not only affects speed but also determines your ability to reach your intended destination.

Let’s dive into each point and uncover the secrets they hold!

1. Close-hauled: This point showcases utmost efficiency against an upwind or beating course. By steering as close to the wind as possible, sailors can maximize their velocity made good (VMG) towards their desired location. However, it requires precise trimming and constant adjustments to keep sails full without stalling them.

2. Close Reach: When you ease slightly from close-hauled, you enter this versatile point. It allows for increased speed by harnessing more lift from airflow across sails while maintaining efficiency upwind. The close reach can be your go-to when trying to make headway towards a target upwind.

3. Beam Reach: Here lies sheer exhilaration! Your sails fill with maximum power perpendicular to the wind direction, propelling you comfortably at good speed across open water. The enticing balance between stable sailing conditions and thrilling progression makes this point ideal for leisurely cruises or having some fun with friends out on the water.

4. Broad Reach: As you continue turning away from directly perpendicular windward orientation, the sailboat starts moving closer to running downwind. The broad reach showcases both elegance and excitement as your boat gracefully glides through the water with exhilarating speed. It’s a sweet spot where veteran sailors masterfully handle their craft, sticking harmoniously between swiftness and control.

5. Running: Picture this: You’re on a sailboat racing downwind, feeling the wind in your hair, spray in your face, and that pure adrenaline rush! Welcome to the running point—where boats effortlessly surf along waves propelled by nothing but nature’s breath. While it might appear simple, maintaining optimal control while maximizing speed requires subtle adjustments like using weight distribution or trimming sails strategically.

6. Dead Downwind: To complete our journey across the points of sail diagram, we find ourselves at dead downwind – sailing directly away from the wind. In this position, you’ll witness simplicity at its finest as you let nature do most of the work. However, an experienced sailor knows that even in simplicity lies a challenge; staying perfectly aligned without accidental gybing or losing momentum demands focus and skill.

Understanding these points of sail unlocks infinite possibilities for sailors worldwide. Whether you’re competing in regattas striving for ultimate performance or embarking on leisurely journeys exploring vast blue horizons – mastery over these angles is essential.

So next time you step aboard a sailboat, take a moment to appreciate the power behind each diagram point and let it guide you towards sailing excellence and unforgettable nautical adventures!

Navigating Your Way with a Points of Sail Diagram: A Comprehensive Breakdown

Navigating your way through the vast sea or ocean can be an exhilarating yet complex task. Sailors and boating enthusiasts face a multitude of challenges, from changing wind conditions to varying water depths. To add to this complexity, sailors must also have a thorough understanding of the points of sail diagram, which acts as a compass in guiding them towards their destination.

The points of sail diagram is designed to help sailors determine the most efficient angle for their sailboat’s sails in relation to the wind direction. It provides a visual representation of how a sailboat should maneuver depending on the wind’s course. By understanding this diagram, sailors are able to make precise adjustments and harness the power of the wind effectively.