Search form

Docking a dual rudder sailboat.

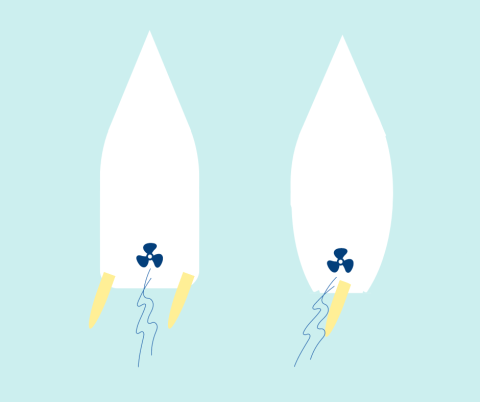

Dual rudders, also referred to as twin or double rudders, are becoming more and more common in modern sailboats, both cruising and performance yachts alike. Since dual rudder boats handle differently than single rudders when maneuvering under engine power, it’s important for our charterers to know which boats in our fleet have dual rudders and to understand differences in the way they handle in tight spaces like dock slips and narrow fairways.

First, let’s have a look at the advantageous reasons dual rudders are becoming popular in modern boat design, as well as the challenges they can present to the uninformed. We’ll then give you some tips to help you get prepared for successful maneuvering in and out of the marina.

Dual Rudder Advantages

- To make for roomier cockpits and more space below deck for accommodations and storage, design trends are leaning toward wider transoms. Dual rudders improve the handling of a boat with a wide transom.

- Dual wheels accompany dual rudders, which means a more open cockpit layout and better visibility for the driver on the helm.

- Dual rudders facilitate better tracking. When the boat is heeling, there is always one rudder in the water, which means better control and a reduced tendency to round up.

- The propeller lies forward and between the twin rudders rather than in line with a single rudder. This means there will be no prop walk effect when backing up in reverse.

Dual Rudder Challenges

- Bow thrusters can help compensate in difficult conditions, but before you attempt to use bow thrusters, focus on learning how to dock without them first, and be sure to read this article: Bow Thruster Basics

Twin Rudder Dual Rudder versus Single Rudder Modern Sailing.png

Boats with Dual Rudders in the Modern Sailing Fleet

Helix (Beneteau Oceanis 30.1), Traharta (Beneteau Oceanis 35) Survivor (Beneteau Oceanis 38), Liberty (Beneteau Oceanis 38.1), Ry Whitt , (Jeanneau Sun Odyssey 409) and Attitude Adjustment (Beneteau Oceanis 41) are equipped with twin rudders and helms. Survivor and Liberty also have bow thrusters.

Tips for Docking a Dual Rudder Boat

Departing the Dock Slip

IMPORTANT: With a single rudder, when you apply a quick burst of throttle, prop wash over the rudder allows you to steer the boat without needing to accelerate. With dual rudders, you’ll need a longer burst to accelerate the boat enough to steer.

- If you need to turn your stern to starboard to head left out the fairway, then turn the wheel to starboard. This applies to B Dock boats Helix , Traharta , Survivor , and Liberty .

- If you need to turn your stern to port to head right out a fairway, turn the wheel to port. On A Dock boats Ry Whitt and Attitude Adjustment , back up straight, and once sufficiently clear from the dock, turn away from shore to avoid nearby shallow areas. (Rocks - ouch!)

- You’ll need to use your best judgement to determine how far to turn the wheel – it will depend on the wind and current.

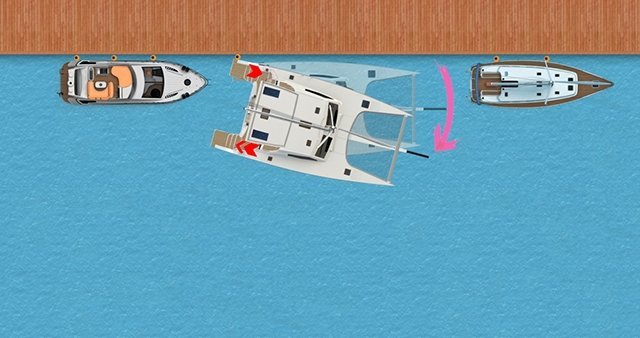

Let's imagine you're backing Traharta out of her slip on B Dock. Put the engine in reverse gear and apply a bit more throttle than you normally would on a single rudder boat. Keep the boat as straight in the slip as possible as you begin to back up. When the boat is 3/4 of the way out of the slip, turn the wheel to starboard, shift the engine into neutral gear and allow the boat to glide backwards into your starboard turn. When clear of the dock, turn the wheel to port, put the engine in forward gear, and slowly increase throttle as you head out of the fairway.

While you're out on the water, we highly recommend you take some time to practice maneuvering a dual rudder sailboat in a safe area like an unoccupied mooring field. (Of course, always check the charts before entering an unfamiliar area to ensure adequate depth.) You can use mooring balls or buoys as points of reference as you get a feel for how the boat maneuvers. Be sure to give plenty of room for error around fixed objects. You’ll especially want to practice slowing the boat to get a feel for the speed at which it loses steerage. This will help you to better judge the minimum amount of speed you'll need to maintain control of the boat as you maneuver.

Entering the Dock Slip

Heading down the fairway and approaching the dock, once again, you’ll need a bit more momentum than you would in a single rudder boat. As you begin to turn toward the dock slip, don’t slow down too much or you could lose steerage and miss. Maintain momentum until you have completed the turn and the boat is aligned with the slip. When you enter the slip, at the last moment, reverse the engine and throttle up to stop the boat. Because you entered the slip with more momentum than you would on a single rudder boat, you’ll also need to apply more RPMs to stop the boat. Again, use your best judgement on how high to throttle up based on the conditions.

Want More Training?

Here's some of the ways you can get docking practice and training with one of our experienced instructors:

- ASA 118, Docking Endorsement Clinic

- Platinum Fleet Dockkng & Maneuvering Clinic

- Development Sails

- Private Lessons

Need Help at the Dock?

Whenever you find yourself approaching a docking situation that feels uncomfortable for you (such as in a strong wind), it's always okay to ask for help. Call the Modern Sailing team on VHF radio channel 71 if you would like some help with a slip-line departure or dock entry. Please be aware that only our licensed and certified instructors are qualified to provide docking instruction, but a fleet team member standing on the dock can help you cast off or catch your lines as you depart or come in. We're happy to help!

Did you find this article helpful? See our Member Resources library for more like it.

Share This Page

Testimonials.

I would definitely recommend Modern Sailing to anyone who is interested in learning to sail the right way.

The meeting room was quite adequate and the location most convenient, but the course outline and instruction were outstanding. Modern Sailing is fortunate to have such a well organized instructor in Mr. Stan Lander who teaches very well from a rich professional background. Mr. Lander was generous with his time and patiently in helping students who needed more attention or time in understanding various aspects of the curriculum.

Captain Jeff Cathers is really cool. I had such a great time on the Farallones Day Trip . It was actually my very best day of 2020. Thank you so much for coordinating the trip.

View All Testimonials

Follow us on Social Media

Modern Sailing School & Club

Sausalito Location 2310 Marinship Way, Sausalito, CA 94965 (415) 331-8250 (800) 995-1668

Berkeley Location 1 Spinnaker Way, Berkeley, CA 94710 (415) 331-8250 (800) 995-1668

Map / Directions

You are here.

Attainable Adventure Cruising

The Offshore Voyaging Reference Site

- Coming Alongside (Docking)—The Final Approach

In this chapter I’m going to focus on the final few boat lengths of the approach to a wharf or floating dock. This is perhaps the most important part of the whole operation and where we see the most SNAFUS, usually because the boat does something the helmsperson did not expect in the final few seconds of the approach, often when he or she applies reverse to stop.

The key point being that if we are going to be happy boat handlers we must understand and anticipate how the boat will react.

And this vital understanding lies in the things we learnt in the last chapter. Once moving slowly or stopped:

- In reverse the stern will react to prop walk.

- In forward the stern will react to prop wash over the rudder.

To make our approaches easy and trouble free, all we need to do is set up and execute the approach so that these fundamentals work for, not against, us.

Let’s get our boat alongside so that the deckhand can step (never jump) ashore and get the required lines on without fuss or shouting.

Login to continue reading (scroll down)

Please Share a Link:

More Articles From Online Book: Coming Alongside (Docking) Made Easy:

- Introduction to Coming Alongside (Docking) Online Book

- 10 Tips to Make Coming Alongside (Docking) Easy

- Coming Alongside (Docking) in 4 Easy Steps

- Rigging The Spring That Makes Docking Easy, Or an Alternative

- 10 Ways to Make Your Boat Easier to Bring Alongside a Dock

- Coming Alongside (Docking)—Manoeuvring in Close Quarters

- Coming Alongside (Docking)—Taming the Wind

- Coming Alongside (Docking)—Backing In, Part 1

- Coming Alongside (Docking)—Backing In, Part 2

- Q&A, Coming Alongside (Docking) With Twin Rudders

- Q&A Backing Out of a Bow-In Med Moor

- 14 Tips for Coming Alongside Single-handed—Part 1

- 14 Tips To Come Alongside Single-Handed—Part 2

- Leaving a Dock Against an Onshore Wind—Part 1

- Leaving a Dock Against an Onshore Wind—Part 2

- Going Alongside (Docking) in Current—Fundamentals

- Going Alongside (Docking) in Current—Turning in Confined Spaces

- Going Alongside (Docking) in Current—Backing In

- Going Alongside (Docking)—12 More Tips and Tricks

My comment is “no comment, because this puts literally everything I’ve experienced handling a heavy full-keeler in a docking situatio in one place”. Great work, you two.

Thanks John, my wife finally understands what we been talking about for years.

Jim, your lucky! John, I am finding these chapters on docking very very useful. We have a 36ft steel Roberts Spray with a full length keel…… she loves going in a straight line no matter what the conditions, but absolutely hates getting into tight berths. These docking hints may well save a lot of embarrassment and save others from ” Feeling The Steel”

Hi Marc, Jim, and Lee,

Thanks very much for the kind comments, I really appreciate the encouragement, particularly since I’m wrestling with the next chapter.

Just perfectly described, adds a lot to my own (sometimes painful) experiences 😉

One thought on reverse propwalk when needing to go a couple of boat lengths backwards: I position the boat in some angle to the intended direction so the propwalk “puts me straight” before the boat starts to move. I usually give a good lengthy burst backwards so I gain some speed, them idle out completely to remove the then unwanted propwalk. This way I am completely able to steer straight backward. Of course this works best with more heavy boats as they tend to run some lengths after they finally started to move…

Absolutely a good technique. We have an entire chapter coming, on backing into tight places.

Thanks for packaging this up so neatly. We have learned a good deal of this stuff by trial and error since getting our first “big boat” nine years ago, but under pressure it is hard to get it right when one thinks “How does that work in this situation?”, but we are getting better. I am going to print out this book so that Pat and I can thoroughly digest it and gain a better understanding of the forces at work and how to use them to our advantage. You make it look so simple, but that obviously comes with great experience.

Thanks for the kind words and I’m very glad that we have been able to simplify things. The interesting thing is that while struggling (and it was that) to come up with simple explanations we too have learned a lot. As they say, sometimes the best way to improve our understanding of something is to try and explain it!

Thanks for your informative well written posts on docking and manoeuvring! I look forward to the next chapters, especially backing into tight quarters(with a long keel)! Keep up the good work!! Best regards -> Christian

Hi Christian,

We will be publishing an entire chapter on backing in. We even have a video all done to illustrate it. I think it will be the chapter after next.

Great article and well thought out. My 29′ Paceship has a very nasty prop walk that I use to great effect. My slip is sort of med style in that its up against a wall, is very tight (11′ and me with a 9’8″ beam) with a pylon at midships on either side (but I don’t have to anchor first). Most of the boats at our yacht club have difficulty and/or “chicken out” and nose straight in (and then have to push themselves out hand over hand on the other boats). In fact, everyone usually stops doing what ever they are doing and watches (and silently rates) any docking effort but I seem to have it down to a science that only has to be modified very slightly depending upon significant winds and currents (we’re in a river entrance). My uncle, who taught me to sail, had the same type of boat for about 30 years and when I took him and his wife sailing he took one look at the slip and gave me back the tiller to put it in which I did effortlessly and singlehandedly – prompting his (ever “helpful”) wife to remark (“he NEVER docks that well!”). Absolutely made my month… 🙂

My “secret”…. I steam perpendicularly past the slip about 3′ away from the bows of the boats on either side… as I (personally in the cockpit) pass the anchor of the nearest boat (to my starboard), I throw the boat into reverse and go hard over on the tiller to point the boat away from the wall. The boat turns about it’s Genoa winches so with a bit of momentum, I let the prop walk the stern of the boat 90 degrees and then right into the slip. As soon as it’s lined up, I put it in neutral, centralize the tiller and use the momentum I’ve built up in reverse to let it continue into the slip. As I’m passing the pylons on either side, I grab and cleat my spring lines from the pylons (which stop me from hitting the wall if my engine fails) then wait until I’m almost at the wall before giving it a bit of forward to come to a gentle stop. I didn’t have people to go with me much when I first learned so do everything single handed.

It’s VERY important to have the spring lines set up at the exact point of balance of the boat (so that the boat doesn’t turn one way or the other when you pull on them). I find that if I’m single handing it to a dock like you’ve shown above, I come in exactly as you suggest and then can reach out and throw on a long springline to a dock cleat while I’m still in the boat and then I use the prop to stop the boat just as the springline is becoming tight (and to hold the boat on to the dock while I get the other lines on). Reverse if the dock is to port and forward if the dock is to starboard. They key is as you suggest, to have just enough way on to maintain steerage but NO MORE.

A properly setup spring line, understanding the conditions and your boat’s behaviour (prop walk, windage, rudder effectiveness and how fast and about what it turns) as well as knowing your rudder is USELESS unless the boat is moving through the water (not the same thing as moving against the wind or dock) are critical to being able to consistently dock without drama. A local gas dock is in a fairly strong river (3-4 knot current consistently) and it is great fun to watch (usually non-local) people ignore our warnings and come in from the wrong direction (with the current) flailing away with the rudder to no effect because they don’t understand that if the boat is coasting along with the current, it’s not actually moving in the water and the rudder is USELESS. They often say… my steering just didn’t work at all but I had lots of steerage on (not understanding that they were moving against land and not water).

I learned to “dock” in floatplanes before my sailboat so I had to learn all about windage and prop walk… chewing up bystanders or other airplanes/boats with your prop isn’t the way to win docking contests! 🙂 It is absolutely critical to know how your boat handles before you get anywhere near the dock. When I first got mine, I spent hours practicing bringing it to a perfect stop alongside a race bouy on any heading in pretty much any wind/current condition. You’ll never have conditions that bad up against a real dock and the plastic race bouy isn’t going to scratch your boat or taunt you if you misjudge.

I will be publishing a post on backing in soon and will look forward to getting your wisdom then.

Hi Again Brent,

Another member just pointed out to me that my above comment sounded harsh, and he is right. Sorry. That said, it was not my intention to be rude, but the problem is that if I engage with comments that are on subjects of future chapters, that tends to take on a life of it’s own and use up much of my time, so said future chapter gets delayed.

That’s why I ask at the bottom of nearly every post that members stay on the topic of that particular post.

No worries John… it wasn’t taken that way. Newbie here and I sort of thought I was on topic as the second bit was about docking alongside but I see your point. I look forward to the next chapter.

Thanks for your understanding. I’m probably way more sensitive about this that is warranted because writing this Online Book is taking everything I have…and then some!

Great stuff. I’m no expert on monohulls, but it all rings true, particularly comments on steerage way, planning, and bursts of throttle.

Catamarans, specifically sail power with keels, have another trick, helpful when you need to move sideways. I’ve parked in bulkhead spots shorter than my diagonal measurement.

Although cats generally have minimal prop walk (engines often counter rotate), most have some. They also have the “bulldozer” steering mode, where they pivot in one spot by opposing engines, and the one engine steering mode, where a single engine, accelerates, turns, and can make the boat slide sideways. Thus, if you alternate buldozer steering and one-engine turns, you can slide the boat sideways. Obviously, light winds and currents are required, and an extra set of eye at the bow is really handy, since you may work it very close.

The down side of cats in a marina, of course, is massive windage and shallow keels. You can’t be timid with speed or throttle, and you need to have a bail plan. A well though out bail never looks foolish, not compared to pinballing around!

As John repeats many times, a simple set of rules is not enough. You need to study how the boat actually responds to combinations of inputs. I think it helps that I have to back into a slip in a cross tide and wind; it makes you think and observe.

Yeah, twin engine cats are very cool for manoeuvrability. A friend of mine had a twin power cat with outboards and I had a blast some years ago getting in and out of tight places, even with a far larger disabled monohull lashed alongside. Bottom line you can beat twin engines in tight places and the further they are apart the better it gets.

I’ve been following these articles and tried some techniques.

However, the engine/shaft on my Mirage 33 is offset at an angle to port to eliminate prop walk. It does pretty much eliminate prop walk. Some techniques with prop walk do not work for us offsetters.

Prop wash on the rudder has minimum effect. When reversing, it pulls water in pulls water on the port side of my rudder, and not much so it does not pull much to port when the rudder is to port and practically nothing when the rudder is pointed to starboard.

I noted that Mirage stopped offset propeller in later models.

No questions, but comments and suggestions are welcomed.

I have no experience with an offset but it seems to me to be killing a fly with a sledge hammer as prop walk is only a problem when the boat is not moving relative to the water and the rudder has not yet got any effectiveness. You are right in that the prop “wash” doesn’t have much of an effect on most rudders as it’s a fairly contained stream compared to the normal flow of water over the rudder. The prop “walk” is easily thought of as a paddlewheel effect – at zero relative motion to the water, the blades actually try to “walk” the stern in the direction of rotation as well as pull water backwards over them (there are components of force both ways). To be most pedantic, what’s actually happening is that prop is trying to rotate the boat around the shaft but of course the keel and the water have something to say about that and the water can move. The water at the bottom of the blade is marginally more effective than close to the hull which introduces a lateral force (there is also a vertical component but the weight of boat easily counteracts that). Once the boat is moving through the water, the rudder easily has enough effectiveness to overcome the lateral force. It actually happens in forward as well but the effect is not as noticeable because the prop is much more efficient at pushing than pulling so the magnitude of the force in the desired direction (forward) is much higher than the lateral motion of the prop walk.

With propeller airplanes, we call it the P-Factor. It’s a hell of a lot more powerful and you HAVE to take it into account if you don’t want to ground loop your airplane. The bigger the engine, the more noticeable the effect. Airplanes with nose wheels (like most Cessna’s and Piper small airplanes) have much less of an effect than “tail draggers” as the nose wheel counters much of the lateral force and can be steered into the direction of the force. WW2 fighters with huge engines and tail drag configurations like the famous P-51 Mustang demanded that you put the power on gently until you had enough airflow over the rudder to counteract it. There are planes with offset engines as well but it’s overcomplicated in my humble opinion as prop walk is neither good nor bad… just another factor to be taken into consideration when dragging your pride and joy into tight spaces. Like the wind or. current, you can use it to your advantage – or it can make things a lot worse if you don’t plan for it. Interesting about the Mirage and the offset… I wasn’t aware of any boats that did that.

Hey Brent, Interesting theory. P-factor, as applied to ‘planes is actually a result of the prop operating at an angle to the airflow as is the case with most inboard sailboat installations with respect to the flow of the water. This angle to the flow results in the descending blade having a greater angle of attack, or “bite’, than the ascending blade, therefore causing greater thrust on that side and a tendency to turn in that direction. Ask any CFI or google it. There are other forces at work also: Torque, which you mentioned, spiraling slipstream and gyroscopic precession, which may or may not affect sailboats. P-factor disappears when the prop is operating with the thrust parallel to the flow, as with a saildrive and when the ‘plane levels in cruise, for example. The other effects you mention are new to me. A fascinating subject for sure.

I’m sorry, but I just don’t have any good answers for a boat with an offset prop since prop wash and prop walk are the key to easy close quarters boat handling. That said, installing a balance point spring as I detail in earlier chapters will certainly go a long way to helping out and would be my first step.

Exactly… I didn’t want to get into every single detail but the P Factor is very close to what happens with our sailboats albeit in air versus water. I will disagree though that it “disappears” when the plane levels… it’s always there but the magnitude is such that it’s very small relative to the forces imposed by the rudder in forward motion at design speed… you’ll feel it on your rudder if you don’t have the rudder trim set correctly. I have far too many hours instructing ab initio students to fly (and doing ground school) to forget those details! The gyroscopic precession (a force exerted on a spinning prop will act 90 degrees in the direction of the rotation from the axis in which it was applied) is the one area where there isn’t a great similarity… in a taildragger, when you lift the nose on a clockwise rotating prop, the force that you applied to the top of the spinning prop arc will act as if it was applied to the right side of that arc causing the nose to go left. It’s even worse in helicopters. In a sailboat, I guess if you did a very hard turn at full speed, you might be able to measure the stern sinking or raising depending upon the direction but it would be pretty slight. Not nearly as impressive the first time a student shoves the stick forward to lift the tail!

I recall from my WWII airplane model building days that two-engined fighters such as the Lightning P-38 and the de Havilland Mosquito had contra-rotating props (inward, I believe) to counteract this effect and to give them equal facility at rolling either to port or starboard. Of course, you’d only see that on a catamaran in the watery situation, and I don’t know if cats generally have contra-rotating props. It strikes me as a sound idea.

Cool! So what’s the MTOW of your boat? (tongue in cheek – sorry John).

Give or take about 14,000 lbs… but I think Vr would be about 400 knots which is well beyond the range of my little 12 HP one lung Yanmar :-).

Timely article…. As we are very new to docking. and currently we are moored in Sambro, the wind has been very strong. So far is has been pushing directly on our port side pushing us away from the dock.

I knew about prop walk, and have been doing as you said… pulling into a port side dock, turning and then prop walking which tends to swing my bow out. Hadn’t considered the momentum factor and that I should let the prop walk twist my bow away. Or the idea that turning on a starboard side dock will help negate the prop walk. Very useful info.

I’m really glad to know it’s working for you, makes all the work to write these chapters feel worthwhile.

A class like American Sailing Association’s docking endorsement (118) or even a few hours of private instruction is a truly worthwhile investment, and may just be the second-best use of boat dollars right after a Morgan’s Cloud subscription!

Thanks for the kind words. One point: those who are new to docking need to be very careful in who they select to teach them since, as Chad discovered above, many, maybe even most, experienced sailors are actually pretty bad at close quarters boat handling and clearly don’t understand the basics of prop walk and prop wash. And this seems to go double for some of those that have boating-teaching qualifications.

The point being that someone new who uses this Online Book and applies the fundamental theory in a thoughtful way, and practices a bit, will often be way better off than if they listened to an “old salt” who will just transfer his or her own bad habits and lack of understanding to the poor newbie.

Great treatise on the simple yet complex challenge of docking a boat. Which often feels like chewing bubblegum and patting your head at the same time while doing a jig.

Love your simple guidance. NO CREW LEAVES THE BOAT TILL IT IS STOPPED AND THEY CAN WALK OFF SAFELY!

Couple of years ago I found my go to docking method. A “stern spring bridle” . It is a line run from mid ships along the side I plan to dock. Long enough so that I can toss the middle section of the line out over a cleat from the boat, and bring the tail back in to a stern cleat. I have one of those typical sailboat stern cockpits and I often am the solo handler of the boat.

The line once over the dock cleat provides the same spring line connection you describe. The boat control is the same. Yet I have the line tail back on board the boat and have not had to step off the boat. I put the boat at idle in gear and the boat (even if it was a few feet from the dock to start) snuggles up nicely to the dock against teh fenders. Assured that the boat is not going anywhere, I can then leave the helm (and boat – step to the dock) and secure the other lines (bow and stern – which are layed out on the rail in preparation) to dock. Hop back aboard and shut down engine.

Keep your ideas and writings coming. They are great sharing to enjoy when the snow slows down my sailing adventures.

Sounds like we are on the same page, and thank for the kind words. Reminds me that I need to get back to this online book with a couple more chapters.

- Find A School

- Certifications

- North U Sail Trim

- Inside Sailing with Peter Isler

- Docking Made Easy

- Study Quizzes

- Bite-sized Lessons

- Fun Quizzes

- Sailing Challenge

An American Sailing Association Educational Series

Learn how to dock a sailboat under sail, or under power, in a variety of different scenarios. Sailing legend Peter Isler walks us through the process using animations, illustrations and live action footage. Understand the techniques and skills required by both skipper and crew in order to make your docking experiences safe and easy. The videos are based on the learning material featured in the ASA textbooks Sailing Made Easy and Basic Cruising Made Easy .

This Series Features the Following Lessons:

Docking Under Power

Cruising Catamarans

It's time to apply the skills we learned in the docking drills video to returning your boat safely to the dock. As we've learned every boat and every docking situation is different so let's keep things simple for our lesson on bringing the boat back into the dock. To solidify your fundamentals practice on a day where there is a light wind that's aligned parallel to the dock. We will make an upwind approach - that is always preferred - and the dock will be on our port side.

Open Water Drills

Docking a larger sailboat under power can be challenging. This episode features great open water drills to reveal characteristics of your boat that will help you learn to maneuver in tight quarters with control and confidence. Understand how a sailboat behaves at slow speed and in addition to the rudder learn about other turning forces - such as the wind, prop walk, and prop wash.

Returning to the Dock

Departing from the Dock

It's time to apply the skills we learned in the docking drills video to getting your boat out of a slip safely. Bear in mind every boat and every docking situation is different. But if we keep things simple, success is a sure thing! For your first attempts, find a slip that is aligned bow to the wind. Learn how to configure your docklines for a simply departure, make sure your crew is safely aboard, and use your engine to control your speed in order to make a smooth and safe departure.

Docking Under Sail

An ideal approach.

What is the the ideal approach for docking a sailboat under sail? In a perfect world the wind will be blowing parallel to the dock so you can approach on a close reach and tie up pointing into the wind. Learn how to prepare your crew for docking, how to safely control your speed on your approach to the dock, how to safely step off the boat onto the dock, and finally how to secure your boat once you have docked.

The Downwind Approach

A good sailor must know how to dock their boat in all types of conditions. Although docking under sail in a downwind scenario isn’t desirable and should be avoided, there are situations that mandate such a skill. Learn the correct steps and methods to adhere to as you steer the boat into a downwind slip.

BONUS: How to Hang Your Fenders

Tying off fenders is something we have to do all the time so how should they be hung and how should you tie them? Different situations call for different applications, but generally speaking the best thing to do is hang the fenders from amidships from the lifelines just kissing the water.

The “Docking Made Easy” videos are presented by Cruising World in association with Beneteau America.

Other Docking Related Resources

Bite Sized Lesson Videos

We know that learning to sail can be overwhelming and there is a lot to take in. In an effort to help we’ve created a series of “Bite Sized Lessons” taken straight out or our textbooks.

Knots Made Easy Videos

There are as many sailing knots as there are stars in the night sky — or so it seems. But the reality is that most sailors can get along with only knowing a few, as long as they’re the right ones.

Sailing Challenge App

A cutting-edge, mobile gaming app designed as a fun learning aid to help illustrate the principles of sailing in a rich interactive and entertaining format. Available on iOS & Android.

- Learn To Sail

- Mobile Apps

- Online Courses

- Upcoming Courses

- Sailor Resources

- ASA Log Book

- Bite Sized Lessons

- Knots Made Easy

- Catamaran Challenge

- Sailing Vacations

- Sailing Cruises

- Charter Resources

- International Proficiency Certificate

- Find A Charter

- All Articles

- Sailing Tips

- Sailing Terms

- Destinations

- Environmental

- Initiatives

- Instructor Resources

- Become An Instructor

- Become An ASA School

- Member / Instructor Login

- Affiliate Login

Boating Tips

For recreational and professional mariners, crosswind docking like a pro.

Docking a boat in a slip on a calm day is pretty straightforward for most operators once you’ve done it a few times. But add a crosswind (or cross current) and it can quickly turn into a scary (and expensive) nightmare. It need not be that way – it will take practice and careful attention to all the forces at play.

Let’s start by remembering the concept of “walking” a twin-engine boat. I covered this topic in a prior post here . In a crosswind it is imperative to know how well your boat can walk and its limits.

Also let’s talk about thrusters. They are increasingly popular on boats these days and on smaller boats too. Some old salts may argue that their use is a sign of an unskilled helmsperson. It is true that many people learn to rely on them at the expense of learning basic skills, and they discover this on a windy day when the thruster decides to not work. On the other hand, there are certain conditions in which docking would be impossible without them. In this discussion I’m only considering bow thrusters. There is really no need for a stern thruster on a twin engine boat – the mains can do that job handily.

Crosswind Docking Without a Bow Thruster

First things first – ALWAYS know from where the wind is blowing. Exactly, not a rough guess. In a marina, just look up at the top of all of the sailboat masts. Every one of them has a Windex that points into the wind. And keep looking at them for any changes.

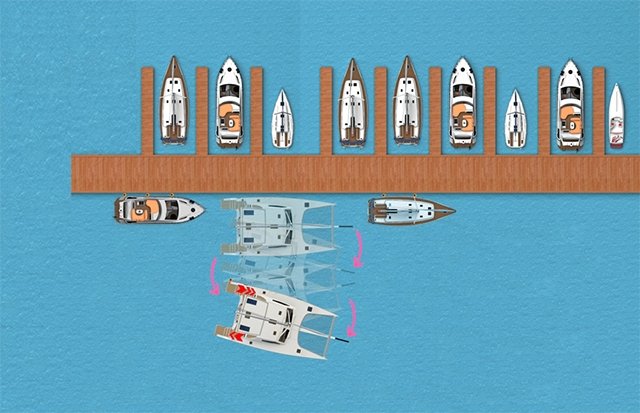

To set the stage, consider the following image. We intend to dock in a slip with a healthy crosswind (or cross current). The obvious risk is that the boat makes hard contact with the downwind corner or the piling. This is what we DON’T want to have happen…

There are two possible approaches – from the upwind side or the downwind side. Some folks prefer approaching from downwind and “use the momentum” of the boat to carry it against the wind and into the slip. This does work, and is really the best option for single engine sailboats with keels that better resist the leeway generated by the wind. With this method, you need to be a bit assertive with the controls, come in a bit faster, and enter with the bow as close to the upwind finger and piling as possible, then turn into the slip.

The above method definitely relies on momentum – if done too slowly the boat will end up plastered onto the downwind piling. A downside to this method is that it does not offer an escape route – it needs to be committed to early.

A better solution for twins is to rely on walking. Recall that a twin can be configured with left full rudder (in this example), ahead on port and astern on starboard with the result of moving forward and sideways. Also, recall that some boats walk better than others – slower displacement boats with big rudders do much better than express cruisers.

So we will leverage this capability in our crosswind docking. Begin by setting up at an angle to the slip with no way on and with the bow as close to the piling as possible without touching…just inches away as shown below. The benefits of being close are that you are closer to your final destination and that an adjacent boat will help block the wind on the bow.

The boat should be angled quite a bit from the slip – this will allow you to better judge the wind effect as you let the stern swing down. All this time you are using only the shifters with rudder amidships or maybe just a few degrees of left rudder.

Continue to let the stern get blown down by the wind while keeping the bow near the piling. You can also start dialing in left full rudder in preparation for walking into the slip. This is the time when you begin to judge how rapidly the stern is swinging and whether or not you have the power (and skill) to continue with the maneuver or back away and try again.

As the stern continues to swing and the boat aligns with the slip, then the controls are set up for walking and the boat is brought in as close to the upwind finger as possible. As you enter the slip you can begin to neutralize some of the rudder and keep the boat parallel. If you begin to “lose the stern” downwind, it is still not too late to back away and reset on the upwind side.

Crosswind Docking With a Bow Thruster

Bow thrusters are spectacular devices that make boat operators look good. But they do have limitations. The most significant is their duty cycle. Most smaller vessels have electric thrusters. Some have proportional control – at 30% power then can run almost 100% duty cycle, but most are either on or off and may be limited to as little as two total minutes maximum per hour. When run too long, they overheat and trip offline (at the worst possible time) so it is important to not run them too much. On a larger yacht with a hydraulic thruster or a dedicated engine for the thruster the duty cycle is unlimited.

When using the thruster to hold position against the wind, the engine controls are REVERSED from the earlier walking method. We are using starboard ahead, and port astern. Basically just swinging the stern to starboard, with the thruster to take care of the bow position. Left full rudder is not needed – perhaps only 10 degrees left or even rudder amidships.

The maneuver begins similar to the discussion above, with setup at the upwind corner with no way on. Note that this can be done from the downwind side as well but realize this – from the upwind side we only need enough power to stop the swing of the stern but from the downwind side we need even more power to force the stern and bow up against the wind.

As the stern swings downwind, engage the thruster and use the engine controls to hold the stern against the wind.

On boats with electric or undersized thrusters it is not uncommon to “run out of thruster” and not be able to use enough main power to stop the stern without overpowering the thruster’s effect. In these cases, it is possible to switch to “walking” mode to help the thruster a bit. By switching back and forth between modes you can ease the boat into the slip. Yes…this takes practice. Just remember to pause in neutral when shifting to let the gearboxes spin down.

One other thing – on most electric thrusters the joystick is momentary-on and your hands will be busy on the engine controls. On an especially difficult docking it may be handy to have an extra crewmember standing beside you to manage the thruster.

Docking a single engine boat in a crosswind is similar, with left rudder to hold the stern up against the wind while the thruster takes care of the bow. The main difference is that the maneuver happens with more headway to maintain stern control. It’s not possible to hold the stern in place against the wind without gaining headway. This is the case where a stern thruster may have some merit. If the wind happens to be on the side that your stern will propwalk to when turning astern, you can use that to good effect.

A word about cross currents – just a little bit of current will have the same effect as a lot of wind. But the techniques are the same. Sometimes the most challenging situation is when the wind and current oppose each other. As you approach the slip, it might not be obvious which one will “win”. As that becomes apparent it might be necessary to switch sides for the approach.

Also – sometimes having NO wind or current is actually a bit more challenging and you end up fishtailing back and forth to make it happen. It is sometimes easier to have just a bit of side force to have something to push against.

And finally – there will be days when there is just too much wind and/or current, and that particular boat just CANNOT be safely moored into the slip. It might be the size of the rudders, or available power, or other factors that make it very difficult without risking damage. Those are the days when it is best to change the plan and find a guest dock or other location to wait out the conditions until they improve. It might not be a reflection on you – it might be physically impossible to accomplish.

As they say – practice, practice, practice!

Leave a Reply Cancel reply

Your email address will not be published. Required fields are marked *

Save my name, email, and website in this browser for the next time I comment.

CRUISING TIPS: Docking

Here’s an excerpt of our recent article on boat handling for catamarans. The original piece, in entirety, can be found in our 2018 Seawind Cruising Club Magazine. Download a copy here .

Of the numerous benefits of owning a catamaran, one which simply cannot be overlooked is the control advantages offered with a dual engine setup as found in most modern cruising catamarans. And while the redundancy of twin engines is a huge bonus for any serious sailor, you simply have to admire the maneuvering possibilities offered in this simple setup.

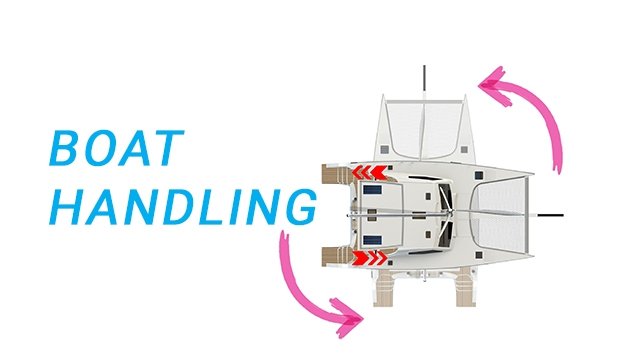

Turning in Tight Quarters.

Turning in Tight Quarters

When the need arises you can turn your catamaran in a 360 degree spin within its own boat length. When entering a crowded marina at slow speeds, hold the rudders on center and use the engines to steer the boat through to the boats berth. To turn to Starboard, apply more throttle to the Port engine and vise versa (again, resisting any urge to touch the rudders). To perform a hard turn to Port, increase the Starboard throttle forward and push the Port throttle into reverse.

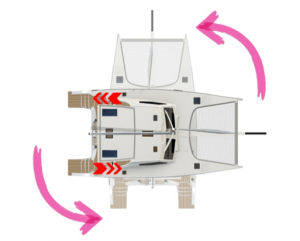

Pushing Off.

Pushing Off

You’re berthed with your Port side-to and have boats tightly packed in front and behind. You are going to need to swing the bow out, clear of the boat ahead before motoring away from the marina. To do this, ensure you have a good fender tied off your rear quarter, you are going to use this to pivot the boar away from the dock. First push the Port throttle into forward at low speed and then engage the Starboard throttle in reverse at a low-medium throttle. Adjust both throttles back and forth to balance the boat in its static position while the bows pull away from the dock. If you are not confident in your abilities to do this unaided, wrap a spring line from the aft cleat to the dock and then back to the boat. Adjust this to prevent the boat from travelling backward and then release once the bow is clear of the boat ahead.

When entering a slip at your marina, the best way by far is to back the cat into the slip rather than entering bow first. On a Seawind the steering station is slightly aft, and outboard which provides better visibility when backing in. You also have twin helms and if dual controls are optioned, favor the side closest to the dock as it is important to keep a close eye on the distance between you and the dock. In tight quarters drive the boat along the pens as you approach your berth then as you would when reverse parking a car turn the bows away from the slip. It is best to then bring the boat to a complete or near stop before engaging in the reverse maneuver. Put the engines into reverse applying more throttle to the side furthest from the dock. Ensure your fenders are out and dock lines prepared. Slowly back the boat into the slip until you can throw your stern line to shore crew or loop onto the aft dock bollard yourself. Be sure to disengage the throttle before doing so and ensure the boat has come to a stop. You can then attach a bow line and shut down both engines.

Through steady throttle control you can actually maneuver your catamaran sideways off a dock. The boat will shuffle sideways crab-like. To start, follow the same steps as if you were pushing off, as described in the previous section. Next, rather than engaging both engines in forward you will reverse the throttle orientation and continue to alternate the throttles from (Port-forward / Starboard– reverse) to (Starboard- forward / Port- reverse) combinations applying more throttle to the side furthest from the intended turn direction. In doing so, you will move the bow outward in one movement and the transom outward in the other and so on.

Here’s the CATAMARAN DOCKING video that walk you through each step slowly:

For more information, please click here:

Ask a question

Leave a Reply Cancel reply

Your email address will not be published. Required fields are marked *

The Boat Docker

A Power Boat Docking Simulator

The Boat Docker Training

The following articles provide all of the information you need to know in order to operate The Boat Docker simulator.

Welcome to The Boat Docker

This simulator is designed to train you to dock your twin engine or single I/O power boat before you actually try it in the water! To get started, click above on “Run Simulator.” Thanks for all the feedback! We are continuously updating the simulator to make it a more effective tool. Please email your questions or […]

New Dock configuration

From: from Deniz Tok: Hello there. I just found out about your sim and I loved it! I can’t stop playing. I have a Searay 450 EB with twin engines and separated shifts & throttles. This sim makes great sense and really helps understanding the physics of the boat. Maybe only the wind physics differ […]

GamePad Bug Fix

Thanks to Roy Lewis for pointing out that the GamePad Controller software produces blank simulator screens in some devices. So, we have added a new menu item to either enable or not enable the GamePad Controller. The default setting is Not Enabled.

Added Gamepad support directly in browser

Hello Everyone, I once again added Gamepad support. This works for both wired and wireless Gamepads. Here is the mapping: B Button – Move Left Stern ThrusterA Button – Move Right Stern ThrusterY Button – Move Left Bow ThrusterX Button – Move Right Bow ThrusterL Button – Left Throttle UpR Button – Right Throttle UpZL […]

Using a Game Controller with Mac OS

From user Pete Harris: Love the simulator ! It’s great for developing muscle memory, so you can just focus on strategy when things get real. It was a bit daunting trying to figure out what game controller to buy, coupled with the worry I was wasting my time, and would not be able to get […]

Inbox Suggestion from user John Torkelson I am in the process of buying a 35 to 45 foot boat and need to make a decision on “do I need side thrusters or not?”. Your simulator is great for helping me make that decision and I thank you for your effort. I do have two suggestions for you. […]

Updated Wind / Water Indicators

We updated the Wind and Water Indicators to improve the user experience. Just click on the + / – symbols to increase / decrease the wind / water speed. Then click on any circle to change the wind / water direction.

We have upgraded our URL to include a new SSL certificate. The new URL is https://theboatdocker.com ! Thanks.

This configuration was proposed by John who asked for a modification to the Man Overboard that would “Simulate backing down on a fish.” The fish moves quite a bit faster than the Man Overboard, otherwise it operates the same. Click on the water to move the fish.

Rudder Effectiveness and Single I/O Prop Walk

Thanks to your suggestions we have added Rudder Effectiveness and Single I/O Prop Walk. You can now select low/medium/high rudder effectiveness from the start menu. Be sure to refresh your browsers on the menu page and then again on the simulator page. For a single I/O with an engine speed of 600 RPM, the engine […]

- 2024 BOAT BUYERS GUIDE

- Email Newsletters

- Boat of the Year

- 2024 Freshwater Boat and Gear Buyers Guide

- 2024 Boat Buyers Guide

- 2024 Water Sports Boat Buyers Guide

- 2024 Pontoon Boat Buyers Guide

- Cruising Boats

- Pontoon Boats

- Fishing Boats

- Personal Watercraft

- Water Sports

- Boat Walkthroughs

- What To Look For

- Watersports Favorites Spring 2022

- Boating Lab

- Boating Safety

Twin Engine Stern-In Docking

- By Ted Lund and Illustration by Tim Barker

- Updated: July 31, 2014

One of the most common docking scenarios for larger, dual-inboard boats is the classic stern-to docking arrangement — better known as backing into a slip. It separates the men from the boys, but with a little prior planning, it turns out to be a fairly straightforward (or backward) easy move.

Dual inboards or stern-drives offer boaters a great deal of control. By utilizing counterthrust (forward on one engine and reverse on the other), boaters can literally spin their boat 360 degrees in a little more than a boat length. The rudders or lower units (in the case of stern-drives or articulating drives like Volvo’s IPS) should always be amidships. The process works with dual outboards, though pivot maneuvers are more problematic due to their narrow set.

A. When nearing your slip, try to plan your approach so that wind and current will work with you, bringing the boat to the dock. Pull a little past your slip and then begin backing with both engines (always with your rudder amidships).

B. As you near the point that you need to pivot, pull the starboard engine in reverse and slide the port engine into forward.

C. As you move parallel to the slip, enter with both engines in reverse, adjusting position by countering thrust and bumping the engines in and out of gear when needed. When ready to tie up, put both engines in forward to arrest the movement and bring the boat to dock.

- More: docking , How-To

More How To

On Board With: Brian Grubb

Installing Clear Acrylic Livewell Lids

Captain of Dive Boat That Caught Fire Sentenced to Four Years

How to Make DSC Fully Functional on a VHF Radio

Boat Test: 2024 Checkmate Pulsare 2400 BRX

Cox 350 Diesel Outboard

Suzuki Marine Unveils New Stealth Line Outboards

Boat Test: 2024 Zodiac Medline 7.5 GT

- Digital Edition

- Customer Service

- Privacy Policy

- Cruising World

- Sailing World

- Salt Water Sportsman

- Sport Fishing

- Wakeboarding

Many products featured on this site were editorially chosen. Boating may receive financial compensation for products purchased through this site.

Copyright © 2024 Boating Firecrown . All rights reserved. Reproduction in whole or in part without permission is prohibited.

- Print This Page

- Text Size

- Scroll To Top

Welcome to the MC Sailing Association

Upcoming Events

2024 regatta results.

“HISTORY OF THE SCOW” Film Proposal Woody Woodruff has been sailing scows a long time and is using his talents as a film producer to make a documentary film on scows: The Project Donate Here

© MC Sailing Association, Inc. 2024. All Rights Reserved.

- Finest Hour

- Publications

Finest Hour 148

Getting there: churchill’s wartime journeys.

Reading Time: 17 minutes

Winston Churchill, Parliament Square, London © Sue Lowry & Magellan PR

- Past Events

- Upcoming Events

- Affiliate and Chapter Events

- Join the Society

- Join Us On Facebook

May 1, 2013

FINEST HOUR 148, AUTUMN 2010

BY CHRISTOPHER H. STERLING

Professor Sterling ( [email protected] ) teaches Media Law and Policy at The George Washington University, Washington, D.C.

ABSTRACT In a time when the world leaders, and their spouses, fly jumbo jets stuffed with aides and staffers, we recall how an embattled Prime Minister traveled to more vital meetings rather less elaborately: an epic tale of Determination for a man his age.

2024 International Churchill Conference

==================

It’s easy to forget, in this time of daily jet travel, that long-distance flying was once rare, cumbersome and uncomfortable, and sometimes dangerous. Flying transatlantic was unusual before 1940; navigation was complex yet rudimentary, landing places limited. And from September 1939, German forces were determined to destroy any British aircraft or ships they came across. [1]

Despite these facts, Churchill traveled farther and more extensively than any other wartime leader. He believed strongly in face-to-face negotiations with his overseas counterparts and their military. As Prime Minister from 1940 to 1945, he made at least twenty-five trips outside Britain, some ranging over several continents and lasting for weeks. He preferred to fly, simply to save time. [2]

And Churchill by then was neither young nor, at least on paper, particularly fit. Aged 65 at the outset of his premiership, working long hours and abhorring exercise, he seemed ill-equipped for stressful travel. Indeed he became seriously ill on one trip, and had health problems on others. He persevered despite the inconvenience and danger. We now know that Churchill was rarely in danger of German attack, but the tension of flying or sailing made planning for his trips complex and nerve wracking for his staff. [3]

On the plus side, Churchill was a seasoned traveler well before taking up residence at Downing Street. He had sailed on many passenger liners, [4] had briefly learned to fly and often flown as a passenger after 1918, [5] and regularly took Imperial Airways flights to the Continent during the 1930s. As First Lord of the Admiralty in 1911-15 and again in 1939-40, he had visited or traveled aboard a variety of naval vessels. He substantially expanded this experience over the five years of his wartime premiership.

FLAMINGOES, FLYING BOATS AND COMMANDO

Churchill’s wartime travels began less than a week after he became Prime Minister. His first five treks were to France during the May-June six-week war, usually in one of three new de Havilland D.H. 95 Flamingo transports of RAF No. 24 (Commonwealth) Squadron, based at RAF Hendon. The twin-engine Flamingo was all-metal—though de Havilland had built only wooden aircraft up to that point. It held twelve to seventeen passengers. The Flamingos were registered G-AFUE, G-AFUF, and R2765, though none was given an individual name, a then-common practice. [6]

GET OUR BULLETIN

Always escorted by fighters (since German aircraft posed a growing threat), Churchill flew to Paris three times; then pursued the retreating French leadership on difficult and dangerous flights to Briare, eighty miles south of Paris, and later to Tours on the eve of French capitulation. The flights were uneventful—and, sadly, so were the talks. Eighteen months later, returning from meetings with Allied leaders in Washington and Ottawa in January 1942, Churchill made his first flight across the Atlantic aboard Berwick, a Boeing 314A flying boat [7] painted in olive drab camouflage with large Union Flags under her cockpit windows. She was flown by British Overseas Airways Corporation (BOAC) personnel under military orders.

The plane was comfortably fitted with peacetime luxury furnishings and food service for VIPs. Her cabin was divided into several compartments, including a dining area and separate bathrooms for men and women. Passengers could move about, and comfortable full-length bunks could be folded down from the bulkhead. Until the arrival of his Skymaster transport toward the end of the war, the flying boat was Churchill’s most luxurious airplane.

Headed for Bermuda and a sea voyage home, WSC climbed into the Boeing’s cockpit and happily sat opposite the pilot with a cigar clamped in his teeth. He was so taken with the plane that he inquired of Captain John Kelly Rogers whether Berwick could fly him home. Assured that she could, Churchill cancelled plans to sail back from Bermuda. Rogers took on a full load of fuel and saved the Prime Minister several days in transit.

Six months later, Churchill made his only Atlantic round trip by air during the war. Only a handful of prewar passenger flights had followed that route, though military aircraft were being regularly ferried across by mid-1942. On 17 June 1942, Churchill and his party boarded BOAC’s Bristol (a sister to Berwick) at Stanraer, Scotland, flying to Baltimore. Ten days later, they returned on a northerly route via Newfoundland.

A trip to the Middle East and on to Moscow in August 1942 (see article following) involved the first airplane assigned specifically to WSC: an American-built Consolidated LB-30A named Commando. Based on the four-engine B-24 bomber but with a single tail like U.S. Navy variants, she was one of a growing number of bombers and transports flying the risky Atlantic (nearly fifty air personnel were killed in the ferrying process over five years). Commando was piloted by William J. Vanderkloot, who had flown airliners before the war. With his navigation and piloting experience, he was appointed as Churchill’s pilot by Air Chief Marshal Charles Portal. He and the plane had arrived from Montreal, conveying three Canadians to Prestwick, near Glasgow. [8]

Despite being assigned to the PM, Commando was a far cry from the flying boats. Her deep fuselage lacked windows (the cargo plane on which she was based didn’t need them); the only outside light came from the cockpit. There were drafts, and at first no heat; the shelves in the back of the cabin were the only sleeping accommodation, though a simple cooking stove was provided. Lacking cabin pressurization, Commando rarely flew over 8000 feet, enough to surmount most bad weather. Her name painted at a jaunty angle under the cockpit, the lumbering giant was painted matte black, for she often flew at night. [9]

None of Churchill’s airplanes was pressurized. Since he was susceptible to pneumonia, a special oxygen mask was made for him by the Institute of Aviation Medicine at Farnborough. He slept wearing it, even with Commando’s low altitude. [10] Some time later a transparent pressure chamber was devised, into which Churchill could crawl, cigar and all, if the aircraft had to climb. But it would not fit into any of his aircraft without disassembling the rear fuselage, and was rejected out of hand. [11]

Churchill ventured abroad four times in 1943, including two of his longest wartime journeys. On 12 January he flew on Commando from RAF Lyneham to Casablanca. The trip lasted nearly a month, including subsequent stops at Nicosia, Cairo, Tripoli and Algiers, and was his final journey on that aircraft.

ASCALON AND THE SKYMASTER

For a visit to the troops in the Middle East six months later, Commando was replaced by a new Avro York, the only British-built transport of the war. Designed in 1941 and first flown in mid-1942, it used the wings, tail, Rolls-Royce Merlin engines and landing gear of Bomber Command’s famous Lancasters, but had a more capacious square-section fuselage. Assigned to RAF Northolt in March 1943, the York also flew King George VI. More than 250 of the type were built, some serving through the 1950s.

Churchill’s York, the third prototype, had eight rectangular windows rather than the standard round perspex windows, an improvement on Commando’s claustrophobic fuselage. She was named Ascalon, after the sword St. George used to slay the dragon, a name suggested by No. 24 squadron’s commander. [12] Ascalon featured a telephone for talking to the flight crew, a bar and a table with an ashtray, and carried a thermos flask, the latest newspapers and books. Engineers even came up with an electrically heated toilet seat, though Churchill complained that it was too hot and it was disconnected.

In August 1944, with Bill Vanderkloot in command, Ascalon flew Churchill to Algiers and then Naples to visit the Italian theater. There were several other segments of this journey before Ascalon returned home. Two months later, in her third, very lengthy and final trip, Ascalon carried Churchill to Moscow by way of Naples and Cairo, then across Turkey and the Black Sea.

True luxury aloft arrived in November 1944 when Churchill was presented with a brand new four-engine Douglas C-54 Skymaster from America. President Roosevelt already used one, dubbed the Sacred Cow. [13] The first C-54 to arrive in Britain under Lend-Lease, Serial EW999 bore no specific name. She was his first aircraft with tricycle landing gear, which meant no more climbing “uphill” while boarding. But since her deck was more than nine feet off the ground, she carried her own boarding steps—no airport then had such equipment. More than 1200 C-54s were constructed during the war; many were converted for airline service (as DC-4s) afterwards.

The Skymaster arrived with an unfinished interior, but Churchill voiced a vague desire that she “look British.” [14] Armstrong Whitworth in Coventry created a paneled conference room with a table seating twelve, sleeping accommodation for six including a stateroom for the PM with a divan, wardrobe, easy chairs and desk. The C-54 reached RAF Northolt in early November 1944, and soon departed on her first Churchill trip, a brief flight to Paris (and back from Rheims three days later) as the PM visited British commanders.

On Christmas Eve 1944, Churchill boarded the Skymaster for Athens, where he mediated the Greek civil war. His pilot was now RAF Wing Commander “Bill” Fraser. [15] His next important wartime trip was to the Big Three conference at Yalta in February 1945. The Skymaster flew first to Malta, and then, adding fighter escort, across Turkey and the Black Sea for the Saki airport serving Yalta. Fraser parked her next to the Sacred Cow, and both planes were guarded by the Red Army; even their crews had difficulty gaining access.

In late March, the Skymaster departed Northolt with the PM’s wife Clementine, who had been invited to inspect Russian Red Cross and hospital facilities. The trip took several days due to a holdover in Cairo while Russian transit arrangements were made. She returned after VE Day via Malta. The PM’s twenty-fifth and final wartime trip was on the Skymaster to Bordeaux (where he relaxed and painted for a week); and then on to Berlin for the final summit at Potsdam. On July 25th, it flew him home for the election returns that ended his wartime travels.

OVER THE SEA IN SHIPS

Though Churchill preferred to fly, surely his most comfortable journeys were aboard His Majesty’s Transport Queen Mary [16] , flagship of the Cunard Line and longtime Blue Riband holder for the fastest North Atlantic crossing. Commandeered for war transport in 1939, she was painted a flat naval grey, and was soon equipped to carry thousands of GIs to Britain (and prisoners back to North America). But some first class cabins staterooms were maintained in pre-war splendor for use of VIPs including Churchill.

Churchill’s first wartime voyage on Queen Mary was from the Clyde to New York in May 1943; three months later, he sailed again from the Clyde, this time for the first Quebec Conference. About a year later, Queen Mary brought him to Halifax, where he entrained for the Second Quebec meeting. This time he enjoyed her amenities both ways, for the Queen also carried him home from New York.

Another former passenger liner used by Churchill during the war was HMT Franconia, a Cunarder since 1923. She provided accommodations, communications and supplies for the PM at Sebastopol during the Yalta talks.

Other seaborne transport was provided by the Royal Navy, including three modern battleships, an older battlecruiser, and two light cruisers. Conditions here were more austere, but WSC would occupy the admiral’s cabin if there was one, or the best cabin otherwise, while deck officers were bumped down or doubled up to accommodate WSC’s party. Staff meetings were held in the officers’ wardroom.

Accompanied by “a retinue which Cardinal Wolsey might have envied,” [17] the PM boarded the new battleship HMS Prince of Wales at Scapa Flow for his August 1941 trip to visit Roosevelt in Newfoundland. Observing radio silence so as not to attract German attention, the battleship carried Churchill’s party to a secret rendezvous in Placentia Bay, which resulted in the “Atlantic Charter” [18] Movie newsreels showed both leaders, their staffs and ships’ crews singing hymns at Sunday morning services on her aft deck. Sadly, many of those sailors were drowned just four months later when the Japanese sank Prince of Wales off Malaya early in December. (See Finest Hour 139:40-49.)

After the Japanese attacks on Pearl Harbor and British Southeast Asia, Churchill left the Clyde for America on 13 December aboard the new battleship HMS Duke of York (a sister to the ill-fated Prince of Wales). Sailing across the North Atlantic in mid-winter was hardly a pleasant trip. But WSC, a good sailor, was indifferent as the 45,000-ton ship pounded gale-force winds before finally reaching Hampton Roads, Virginia.

In August and November 1943, Churchill traveled aboard the aging battle cruiser HMS Renown. Indeed, his longest journey began in mid-November when his party left Plymouth on Renown for Gibraltar, Algiers, and Malta. (See Vic Humphries, “Glimpses from the ‘Taxi’: HMS Renown 1943,” FH 113:24-25, Winter 2002-03.) Though he had hoped to fly home, a serious bout with pneumonia during the trip saw him consigned to the battleship HMS King George V, which arrived at Plymouth in mid-January 1944. His aircraft Ascalon stayed on at Gibraltar for several days, seemingly under repair, in an attempt to confuse German spies watching from nearby Spain. [19]

SMALL CRAFT, SHORT VISITS

On at least three occasions, Churchill spent short periods on destroyers. Six days after the Normandy landings, he took a one-day outing to view the invasion beaches aboard HMS Kelvin which, to his delight, fired on German shore positions while he was aboard. The ship sailed from and returned to Portsmouth. Ten days later he boarded the destroyer HMS Enterprise off Arromanches, France to witness the invasion’s progress. And in August 1944, he was aboard HMS Kimberley to observe troops going ashore on the French Riviera.

He briefly traveled on two light cruisers: Early in 1945, traveling as “Colonel Kent” en route to Yalta, he spent two days aboard HMS Orion in Malta’s French Creek. He used the admiral’s cabin to sleep and shake a fever, and to meet with aides. [20] Homeward bound after Yalta, he rested for a few days aboard the cruiser HMS Aurora in the Egyptian port of Alexandria.

Churchill made numerous short hops to visit troops on the Continent on C-47 Dakota twin-engine transports, usually flown by the RAF. Some 10,000 were manufactured; this military version of the ubiquitous DC-3 airliner saw service in every theater. Seating twenty-one in airline service, but twenty-eight or more in military guise, the C-47 carried anything and everyone. Americans dubbed it “Skytrain” for its flexible capacity. The Dakota was the largest of the twin-engine aircraft which carried WSC.

In addition to the Flamingo for his French flights in mid-1940, Churchill also flew on Lockheed Lodestars. Based on the civilian Model 18 airliner, the military Lodestar first flew in mid-1941 and saw extensive use with multiple services and countries in most theaters. Supplied to the RAF under Lend-Lease, Lodestars served as VIP transports operated by RAF No 173 squadron in North Africa beginning in mid-1942.21 And Churchill flew aboard a U.S. Navy Lodestar from Norfolk to Washington on one of his American trips.

Churchill’s exhaustive wartime travel and vast array of conveyances demonstrate his determination to overcome time and distance, even in the face of discomfort and potential danger. The logistics in arranging these trips were complex; many were pioneering flights over huge distances. But he was a great believer in personal diplomacy, and his methods helped him cement the personal relationships he saw as so valuable to international relations.

1. For the chronology, see Lavery, Pawle and (though less detailed) Celia Sandys, Chasing Churchill: Travels with Winston Churchill (London: HarperCollins, New York: Carroll & Graf, 2003). As for the substance of these trips, there are shelves of books, including Churchill’s own six volume war memoirs.

2. The best and most complete account of most (though not all) of these journeys is in Brian Lavery, Churchill Goes to War: Winston’s Wartime Journeys (Annapolis: Naval Institute Press, 2007). Lavery’s maps, diagrams and photos are especially helpful.

3. The first detailed account of the arrangements that lay behind these many trips is in Gerald Pawle, The War and Colonel Warden (London: Harrap, 1963) whose title is one of Churchill’s travel code names. Pawle’s book is based on the recollections of Royal Navy Commander “Tommy” Thompson, who closely planned many foreign trips and was present for most.

4. For a summary, see Christopher Sterling, “Churchill Afloat: Liners and the Man,” Finest Hour 121 (Winter 2003-4),16-22.

5. Christopher Sterling, “Churchill and Air Travel: Ahead of His Time,” Finest Hour 118 (Spring 2003), 24-29.

6. Email communication, Robert Duck to Richard Langworth, 9 December 2007.

7. Three of the craft, huge for their time, had been purchased for a million dollars each from Pan American Airways, which retained nineothers for its Pacific and Atlantic routes. The purchase was made about the time Churchill was making his aerial round-trips to France.

8. Vanderkloot’s adventures flying Churchill (he died in 2000 at age 85) are related in the accompanying article by his son, and in Bruce West, The Man Who Flew Churchill (Toronto: McGraw-Hill Ryerson, 1975). Unfortunately, the book is filled with fictional “conversations” and suppositions of what people were thinking, and it lacks an index. See also Verna Gates, “Churchill Was His Copilot,” Today’s Officer (October 2004), available here . Vanderkloot’s son recently addressed our Georgia affiliate.

9. Commando was not always black. One of the few photos of the complete aircraft shows her in natural metallic finish, but not the olive drab then so common. See Peter Masefield and Bill Gunston, Flight Path (Shrewsbury, England: Airlife, 2002), 131. Masefield claims Churchill flew this trip on a different though similar transport, the Marco Polo, but no other source—including Churchill’s own memoirs—agrees.

10. T. M. Gibson and M. H. Harrison, Into Thin Air: A History of Aviation Medicine in the RAF (London: Robert Hale, 1984), 80.

11. Jerrard Tickell, Ascalon: The Story of Sir Winston Churchill’s War-Time Flights 1943 to 1945 (London: Hodder & Stoughton, 1954), 79. The subtitle is anachronistic, since Churchill was knighted in 1953, not during World War II. The book is now difficult to find.

12. Donald Hannah, The Avro York (Leatherhead, England: Profile Publication No. 168, no date), 4. Lavery is mistaken when he says this airplane was lost over the Atlantic in 1945 (371). In reality she served for a decade after flying Churchill. The lost aircraft was Commando .

13. Arthur Pearcy, “Douglas DC-4,” Chapter 8 of Douglas Propliners DC-1 to DC-7 (Shrewsbury, England: Airlife, 1995), 105-16. Douglas began designing a larger follow-on airliner to its world-beating DC-3 in the late 1930s. First flown in 1938, the DC-4E (for experimental) was deemed too large by airline managers of the time, and the prototype was sold to Japan. Reworked to a trimmer size, the new aircraft first flew in early 1942. Army and Navy demand for a larger transport meant that none would enter their intended airline service until after the war. Instead, designating them C-54 “for the duration,” Douglas began turning out bare bones four-engine transport aircraft.

14. Several sources quote this line. See, for example, Lavery, 301 (and the previous page, which includes a diagram of the special Skymaster’s layout).

15. Pearcy, 108.

16. This journey was Churchill’s first trip aboard a ship he would sail on often in later years. He published an article about the Queen Mary at the time of her maiden voyage, in The Strand Magazine , May 1936. A reprint is in Finest Hour 121 (Winter 2003-04), 23-28.

17. John Colville, The Fringes of Power: Downing Street Diaries 1939-1955 (New York: Norton, 1985), 424.

18. A good contemporary account of the trip is in H. V. Morton, Atlantic Meeting (London: Methuen, 1943).

19. Tickell, 69-70.

20. Douglas Austin, Churchill and Malta: A Special Relationship (Stroud, England: Spellmount, 2006), 161.

21. David J. March, ed., British Warplanes of World War II (London: Amber Books, 1998), 171.

Despatch Box

The 1954 sutherland portrait, a tribute, join us, #thinkchurchill.

thechurchillsociety

🔹: ICS OFFICIAL Posts dedicated to the leadership and memory of Sir Winston Churchill. 🇬🇧|🇺🇸

Get the Churchill Bulletin delivered to your inbox once a month.

Join the International Churchill Society today! Membership starts at just $29/year.

- Remember me Not recommended on shared computers

Forgot your password?

- Hardware, Software and Controllers

I cannot for the life of me get IL2 to recognize my Rudder inputs

By AuburnAlumni July 22, 2018 in Hardware, Software and Controllers

Recommended Posts

Auburnalumni.

I just got some new Thrustmaster Rudder Pedals to go along with my Warthog HOTAS for both IL2 and DCS.

The Rudders work great in ARMA, DCS...but for some reason....IL2 won't let me assign anything to them. It recognizes that the rudders are there..but when I go into key mapping and move the rudder pedals around...nothing gets assigned. I even tried unmapping everything for YAW, unplugging my HOTAS and leaving the rudders in...nothing.

The rudders are recognized everytime I load in...but it won't let me assign anything to them. Any help would be appreciated.

Link to comment

Share on other sites.

Possible workarounds:

Press rudder for right side, go to Keybinds and when assignment window open release the rudder. If not detec, try with left rudder.

Or try move rudder fast several times.

https://forum.il2sturmovik.com/topic/32207-second-throttle-and-rudder-pedals-not-responding/

https://forum.il2sturmovik.com/topic/37785-toe-brakes-thrustmaster-tfrp-flight-rudder-pedals-for-pc/

=TBAS=Sshadow14

Check there is no double entries in **Games\IL-2 Sturmovik Battle of Moscow\data\input\DEVICES.TXT** Should look like this, but with your part names not X55 ? ?

If your code does not appear clean or numbering is odd (like duplicates or devices on #1,2,4,5 but not 3 Backup file and let game make a new file) Hope it helps. Happy Ruddering.

56 minutes ago, Sokol1 said: Possible workarounds: Press rudder for right side, go to Keybinds and when assignment window open release the rudder. If not detec, try with left rudder. Or try move rudder fast several times. Or: https://forum.il2sturmovik.com/topic/32207-second-throttle-and-rudder-pedals-not-responding/ https://forum.il2sturmovik.com/topic/37785-toe-brakes-thrustmaster-tfrp-flight-rudder-pedals-for-pc/

Yeah I tried your suggestions earlier and neither worked. So aggravating. Pedals are working perfectly in every other game except IL2.

27 minutes ago, =TBAS=Sshadow14 said: Check there is no double entries in **Games\IL-2 Sturmovik Battle of Moscow\data\input\DEVICES.TXT** Should look like this, but with your part names not X55 ? ? configId,guid,model| 0,,| 1,%22619ddf90-117d-11e7-0000545345440280%22,Logitech%20Driving%20Force%20EX%20USB| 2,%22169b4c30-117d-11e7-0000545345440580%22,Saitek%20Pro%20Flight%20X-55%20Rhino%20Stick| 3,%22169b4c30-117d-11e7-0000545345440780%22,Saitek%20Pro%20Flight%20X-55%20Rhino%20Throttle| 4,%2252197440-5038-11e7-0000545345440280%22,vJoy%20Device If your code does not appear clean or numbering is odd (like duplicates or devices on #1,2,4,5 but not 3 Backup file and let game make a new file) Hope it helps. Happy Ruddering.

Bingo! That fixed it. Numbering was off. I deleted the file then relaunched, now its working. Thanks for the tip.

- 1 year later...

Late to the party, but this post saved me after hours of frustration... Turns out I had plugged in many, many peripherals over time and I had reached 11 counts of them by now. IL-2 could see my TPR pedals but they just wouldn't work in game... (I could bind the pedals in the keybinding menu, but pushing on the pedals in-game didn't do anything). I had to delete the "Devices.txt" file and restart the game, then rebind everything and tadaa!! Thanks again! o7

- 3 months later...

Same for me, found this post after an hour of trying to get vjoy to be recognised. Deleting devices.txt worked then it was easy to manually add the rudder axis from vjoy. After checking devices to see which joy number vjoy was. Thanks for posting solution.

- 2 years later...

Red_Von_Hammer

This doesnt work for me, deleted devices.txt and no go.

- 3 weeks later...

Just an FYI

have you checked to see if any of your input files are READ only ?

If so uncheck the read only tab in the properties of each file

Create an account or sign in to comment

You need to be a member in order to leave a comment

Create an account

Sign up for a new account in our community. It's easy!

Already have an account? Sign in here.

- Existing user? Sign In

- All Activity

- Great Battles

- Flying Circus

- Cliffs of Dover

- Create New...

IMAGES

VIDEO

COMMENTS

Sep 24, 2020. Maneuvering a twin-rudder boat like this Beneteau Oceanise 30.1 requires a slightly different mindset. Photo courtesy of courtesy of Beneteau. Twin-rudder raceboats have been with us since the mid-1980s. In the last 10 years or so, they've also become increasingly popular aboard cruising boats, including those available for charter.