You are using an outdated browser. Please upgrade your browser to improve your experience and security.

INSIDE F1H2O

- What is F1H2O?

- The Championship

- The Grand Prix

- Rescue&Safety

The UIM F1H2O World Championship is the 'flagship' international series of single-seater inshore circuit powerboat racing.

Highly competitive, intensely challenging, risky and entertaining, the F1H2O World Championship is the ultimate adrenalin rush and regarded as one of the most spectacular and exciting sports in the world.

The series attracts up to 20 of the world's leading drivers and is a sport that has to be seen to be believed as these diminutive tunnel-hull catamarans enter hairpin turns at over 90mph and top 140mph on the straights.

Picture the scene; 18 to 20 sleek, powerful and lightweight catamarans lining up on the start pontoon. Inside each cockpit sits a lone individual peering through a tiny windscreen. One hand grasps the steering wheel, the other poised over the start button. The tension inside the cockpit is intense as the drivers wait for the crucial start. Beyond the cockpit, an eerie silence descends over the entire arena, all attention fixed on the start.

No sooner does the wait end when 10,000hp of highly tuned brute power bursts into life sending the fleet screaming towards the first corner leaving nothing but a glorious fountain of white spray in its wake.

However, with the thrilling high-speed action comes the risk of ruin as drivers endure brain-numbing G-Forces - their rigs taking hairpin turns at over 90mph while they dice deck-to-deck in often zero-visibility.

Now in its 36th year the four decades of the World Championship have witnessed considerable change and evolution; the seventies and eighties saw multiple promoters and two giant corporations of the sport OMC and Mercury vying for supremacy to be the pinnacle of the sport.

OMC were touting their 3.5litre V8 package that became known as the OZ class, Mercury pushing their 2.0litre engine and called the ON class, the disparity in power would soon lead to bitter wrangling and infighting amongst competitors.

The split came in 1981, FONDA was formed running the ON class engine with the OMC backed PRO ONE run series running the OZ class engine, both rival championships claiming the right to use the title World Championship, a dispute settled by the sport's governing body the UIM later that year awarding the OZ class the accolade.

1984 saw the beginning of yet another twist as safety became a major concern with engine development and increasing power of the V8s taking its tragic toll and signaled the slow demise of the OZ class internationally, ending in 1986.

The door was now opening for the existing FONDA World Grand Prix series to reinvent itself. From 1987 to 1989 there was no official UIM World Championship, and with no challenger, the UIM reinstated the World Championship status and in 1990 the FONDA World Grand Prix Series became the UIM F1H2O World Championship, Mercury's 2.0litre engine the preferred power-plant of the time, the Mercury 2.5litre engine coming in in 2000 and used today.

In 1993 the UIM appointed Nicolo di San Germano as Promoter; his ongoing 30 year tenure has brought stability, a new direction, improved safety and an ever broadening geographic footprint encompassing Europe, the Americas, the Middle East and Asia and with this expansion a growing commercial value.

Over the last 38 years the sport has played out 295 Grand Prix in 33 countries across five continents, 15 drivers have captured the World title, 48 becoming members of the illustrious Grand Prix winners club.

Of the 15 World Champions 8 are multiple title winners; Italy's Guido Cappellini is the most decorated winning 10, Italy's Alex Carella and American Scott Gillman with four, France's Philippe Chiappe, Italian Renato Molinari and American Shaun Torrente with three each, Finland's Sami Selio and Britain's Jonathan Jones with two apiece.

While today's F1H2O catamarans bear a striking resemblance to those in action throughout the 1980's there is a world of difference in terms of driver protection and general safety.

The early boats were constructed from thin plywood with drivers sitting in an open, exposed cockpit with the risk of injury a high probability in the case of an accident.

With safety at the forefront of boat development, British designer and racer Chris Hodges set about improving the situation and constructed a safety cell that was produced from an immensely strong composite material.

Instead of the cockpit being part of the main structure Hodges' capsule was separate and was fitted to the hulls and centre section.

For the first time drivers were actually strapped into their seats. The idea was that if a boat was involved in an accident, the timber hulls could break up and absorb the impact forces while the driver remained well protected inside his cell.

The new device proved itself on several occasions and the U.I.M. called for it to become compulsory, and in the early 1990's Burgess introduced canopies that made cockpits fully enclosed.

In the late 1990's further developments saw the introduction of an airbag in the cockpit that would inflate in a crash to ensure the capsule wouldn't sink before rescue crews could attend.

Over the years boat construction has been developed and today few if any are built of timber, now replaced by modern composites.

In 2023 ten teams and 20 drivers from 12 countries will compete at Grand Prix in Europe, Middle East and Asia for the coveted World title, the prestigious number 1 plate will be carried by the defending World Champion Shaun Torrente driving for Abu Dhabi team.

The Union Internationale Motonautique (UIM) is the world governing body for all Powerboating activities. It is fully recognized by the International Olympic Committee (IOC) and is a member of the Association of the IOC Recognized International Sports Federations (ARISF) and of SportAccord for whom the UIM President serves as President and Board member. The UIM has almost 60 affiliated National Federations. Circuit, Offshore, Pleasure Navigation and Aquabike are among the main disciplines. The UIM has signed a Cooperation Agreement with the United Nations Environment Program (UNEP) to further its range of environmental initiatives and to share expertise.

President: Dr. Raffaele Chiulli General Secretary: Thomas Kurth

Idea Marketing is the sole and exclusive worldwide promoter of the UIM F1H2O World Championship, the UIM-ABP Aquabike World and Continental Championships and the UIM H2O Nations Cup World Series.

The company is the worldwide television and commercial rights holder for all Championships and responsible for all commercial, marketing, television, media and organisational activities.

Founder: Nicolo di San Germano Vice President: Lavinia Cavallero

h2oracing.net f1h2o.com aquabike.net

The F1H2O World Championship is the leading formula in single-seater inshore circuit powerboat racing and was sanctioned by the UIM in 1981.

It is a multiple Grand Prix series of eight events taking place in Europe, the Middle East and Asia.

Points allocated at each Grand Prix count towards the overall World Championship standings.

In addition to the World Championship, points are also allocated for the BRM Pole Position and Team Championships and the Fast Lap Trophy.

A three-tiered qualifying session is run over 60 minutes, the multiple lap Grand Prix run over a minimum 45 minutes, not to exceed 60 minutes.

In 2023 ten teams, 20 drivers from 12 countries plus technicians and support staff will compete for the coveted World title.

DAY 1 Documentation and registration Technical scrutineering Drivers' briefing (compulsory for all team managers, drivers and radiomen of each boat) Free practice Boats and racing equipment (including racing gear of the driver) must be in the pits 24 hours before starting the technical scrutineering

DAY 2 Drivers' briefing (compulsory for all team managers, drivers and radiomen of each boat) Free practice Official Qualifying Podium presentation

Pole position and starting line-ups are determined by a three-tiered qualifying session, Q1, Q2 and Q3 preceding each Grand Prix race. Stateof-the-art timing equipment records the performances of each boat to decide the final classification and starting positions.

Q1 : A twenty-minute session with all boats entitled to run multiple laps at any time during the session, with the 12 fastest progressing into Q2. The times set by those that didn't qualify for Q2 denote their starting positions.

Q2 : After a seven-minute break, the times will be reset and the remaining 12 boats will then run a fifteen-minute session - again they may complete as many laps as they want at any time during that period. At the end of the session the six fastest boats will progress into Q3. The times set by those that didn't qualify for Q3 denote their starting positions.

Q3 : The times are reset and the top six boats from Q2 will run all together for 10 minutes and the arrival order at the finish line will decide their start positions.

If a driver is deemed by the officials to have stopped unnecessarily on the circuit or impeded another driver during qualifying, his times may be cancelled

No refuelling allowed during timed trial.

Every race circuit is different in size, but are generally about 2000 meters in distance. Each circuit has at least one long straightaway and several tight turns, mostly left with one or two right turns.

The turns produce a G-force of up to 4.5 on the driver, which means his weight is multiplied 4.5 times as he makes a tight U-turn at over 100 mph.

Water is a constantly changing unstable unpredictable surface and conditions play a major part in the outcome of each Grand Prix.

With water current and wind conditions varying on every lap and spray being continually showered over the tiny console screen, drivers are quite often driving 'blind' at full speed, mere inches away from their rivals.

In the event of a 'barrel-roll' (capsize), a mandatory air bag installed above the pilot's head will inflate upon contact with water. This enables the cockpit to remain above water until rescue arrives.

All drivers have a self-contained air supply fitted inside the capsule as an added safety features.

LIGHT SIGNALS Each entry must have the electronic time-keeping device and lighting equipment. Compliance is required for scrutineering clearance. Lights signals are used in accordance with these rules to designate specific times or to give instructions to pilots.

Lights and their purposes are as follows:

YELLOW : Reduce speed to 3000 rpm maximum - extreme caution on race course - hold current position - no overtaking - follow pace boat

RED : Race stopped, slow down instantly and return to the start dock, identical to actual black flag.

WHITE AND BLUE caution FLAG : Rescue boats must be given the right of way. A complaint from rescue personnel will be penalised.

Boats that have broken down and pulled to the infield or off the racecourse will be towed to the trailer or the start dock only during a "race stop" condition and if pick-up boats are available.

During the time trials and the race, one crewmember should always remain at signalling area and maintain radio contact with his driver during free practice, timed trials and race.

Each team consists of a manager, two drivers, mechanics, radio coordinator, technical coordinator and equipped with infrastructure such as trailer workshop and welcome marquee.

They should have two catamarans fitted with a 2.5 litre engine and compete at 8 to 10 Grand Prix events in a season.

Imagine this: up to 20 lightweight, 17-foot carbon fibre catamarans hurtling around a racing circuit at speeds topping 220km/h (130mph); all boats are powered by highly tuned V6 outboard engines, each pumping out 400HP at close to 10.000 rpm; they boast an awesome power to weight ratio and weigh in at around 500 kilos.

HULL : Twin sponson, tunnel-hull catamaran

MANUFACTURERS : BABA, Blaze, DAC, GTR, Molgaard, Moore, Victory

HULL MATERIALS : Carbon fibre, Kevlar, synthetic fibre, airex & nomex

LENGTH : 5.10 metres (min)

WIDTH : 2.1 metres (min)

WEIGHT : 550 kg (including residual fuel and oil), the driver with personal equipment, but excluding loose water, circa 380 kilos (not including driver or engine)

FUEL TANK : Carbon constuction, built to accomodate circa 120 litres

ENGINE : Mercury or equivalent outboard engine 6 cylinders 2-stroke

ENGINE CAPACITY : 2.5 litre up to maximum 3 litre

STEERING : Cable with electronic power assist, ratio open to driver preference

GEARBOX : Fixed ratio direct drive

PROPELLERS : As gearbox is fixed ratio, various diameter and pitch from 10.5 by 16 inch upwards (dependant on length of circuit). Forged stainless steel alloy CNC machined

HORSE POWER : circa 400 HP @ 10,000 rpm

TOP SPEED : Over 220 km/h (136 mph)

ACCELERATION : 0-100 km/h (60mph) in circa 3 seconds

BOAT CONTROLS : Hydraulic ram systems controlling engine angle and height operated by a series of switches on steering wheel, dash and foot rest. Foot throttle controlling engine power delivery

SAFETY FEATURES : Cockpit built in composite materials, crash boxes built with energy absorbent foam. HANS head and neck support, airbag, polycarbonate nine millimeter screen and deformable frontal areas to stop penetration in event of accident. Life support system, air bottle and demand valve with helmet attachment used if boat capsizes and driver unable to exit cockpit prior to arrival of rescue boat and team. Inside cockpit the driver is strapped into a carbon hybrid moulded seat with 5 point harness and detachable steering wheel for easy entry and exit. Cockpit canpy latched into closed position for maximum protection against water pressure

The Osprey Powerboat Rescue Team provide rescue services for many powerboat racing events and has a fleet of 6 specialist drop front ambulance boats, 2 of these boats are permanently assigned to providing rescue services to the UIM F1H2O World Championship.

Each boat is manned by four fully trained individuals 2 qualified rescue divers in full kit; 1 qualified helmsman; 1 radio/communications operative; Every member of the crew holds a current Basic Life Support Certificate. Every member of the crew wears a wetsuit as maximum flexibility is required.

Carried on board each boat are the following 2 sets of self-contained breathing apparatus; 1 stabilisation frame in the event of a race boat being upside down; 1 Lift bag to prevent a race boat sinking in the event of extensive damage; 1 fire extinguisher; 1 spine board and stabilisation blocks; 1 oxygen set; 1 radio for communications with the shore based medical team and officials; 1 comprehensive medical kit that contains specialist resuscitation and trauma equipment, details below:

To control catastrophic haemorrhage - CAT tourniquet - ‘Quick Clot’ ACS sponge - 6” Haemorrhage control bandage

To control airway with c-spine control - Suction – hand held with spare spout - Nasopharyngeal airways - size 24 (child) & 28 (adult) -Gels size 4 adult (50-90Kg) size 3 (30-60Kg) - gel sachet on each

To control breathing - Non-rebreather oxygen mask x2 - Ambu-bag, connector & Facemask

To control circulation - Cannula x2, tape, IV giving set, IV fluids – Saline 1000, Gelofusin 500 - Protection and General Kit: gloves, field dressing packs x2, tuff-scissors, stethoscope, saline eyewash, foil blanket, triangular bandage, safety pins, light bandages x2

At each event the team brings A training rig to train and test drivers in escaping from an upturned cockpit. An air compressor to fill diving air cylinders and drivers’ emergency air cylinders carried on the race boats. Generators to provide power A Global Positioning System to ensure the course is laid correctly and to specification.

The powerboat team aiming for 11 world records

- Cork – Fastnet – Cork

- Round Anglesey

- Round Britain and Ireland

- London to Gibraltar

- Gibraltar to Monte Carlo

- London to Monte Carlo

- Napoli to Capri

- Round Britain (under 50ft class)

- The Southern Islands, includes Guernsey, Jersey, Scilly Isles and Isle of Wight

- Miami to New York

- London to St Petersburg

Top Trumps: The fastest motorsports in the world

John Ryan (R): "It’s pretty hardcore"

© Allblack Racing

The team's SL44 is a 1,120hp beast

It’s like driving on a bloody motorway most of the time, it’s so boring John Ryan

Last year, I had broken ribs because of the standard seats that we had John Ryan

These guys have freerun a 21m sailboat

Check out allblack racing's promotional video below….

WORLD SPEED RECORDS

Ocean cup ®, over the horizon since 2013, #nomorerectangles #worldrecord #letsdoitagain, putting ocean back in offshore.

Ocean Cup World Speed Record competitions are designed for sea worthy, offshore craft capable of undertaking independent, extended offshore passages in unprotected waters.

First recognized as a sport in 1904, offshore powerboat racing began as point-to-point, endurance races frequently spanning hundreds of miles of open ocean. In the mid-1990s, offshore became near-shore racing in a track style format, a circuit loop around which boats raced for a number of pre-determined laps. This improved the viewing for the spectators.

During the years, the near-shore course has gotten smaller and shorter. Today a race course is normally a small 5-mile oval as close to the beach as possible. Since the beach drops off quickly, the boats usually run within 150 feet of the surf. Even the outside leg can be clearly seen from the shoreline.

The Harmsworth Trophy (1932) https://youtu.be/6ZqYgy0g67o

- Subscribe Now

- Digital Editions

Top 10 powerboat racing icons that helped make boating what it is today

- Top stories

Hugo Peel explores the top ten power-boating events, people and inventions that have influenced today’s sportsboats...

Powerboat racing may seem a world away from the type of cruising most of us do but the sportsboats we enjoy today wouldn’t be half as good as they are without the racers, designers and builders whose heroic efforts helped shape them.

Auto-boat racing, as it was originally known, traces its history back to the late 19th century and for a brief period was even an Olympic sport, with races staged off the Isle of Wight in 1908. However, it wasn’t until the 1960s and 1970s that the sport exploded in popularity as developments in engineering, materials, speed, safety and propulsion really took off.

Racing was the anvil on which these promising technologies were forged. So what are the ten most significant events, inventions and people that have contributed to today’s impressive levels of performance, safety and utility?

While many of these names and events may be unfamiliar now, they are the stuff of legend to all who recall the glory days of British powerboat racing.

1. The Cowes-Torquay-Cowes offshore powerboat race

Many people regard offshore powerboat racing as the ultimate challenge for craft and crew. Arguably the most challenging race of all and certainly one of the oldest is the legendary Cowes-Torquay competition.

Initiated in 1961 by Daily Express newspaper magnate and keen yachtsman, Sir Max Aitken, who foresaw it would help grow the UK marine industry, it bred a string of British and international heroes and brands. This 200-mile race, now known as the Cowes-Torquay-Cowes, and its coveted Harmsworth Trophy, intermittently awarded since 1903, is still the one all top powerboat racers yearn to win.

The marathon Round Britain Powerboat Race started and finished off Portsmouth

2. The marathon Round Britain Powerboat Race

If a 200-mile race sounds challenging, the 1,500-mile endurance marathon that is the Round Britain Race is on an altogether different scale, yet it proved so appealing that it has been run three times over four decades.

The first BP-sponsored race in 1969 comprised ten stages over 1,459 miles and was won by Timo Mäkinen, a champion Finnish rally-driver in Avenger Too propelled by triple Mercury outboards – he averaged 37mph.

The 1984 race was sponsored by Everest double glazing and attracted famous names, including Italian racer/designer Fabio Buzzi driving White Iveco , a single-step GRP monohull with four 600bhp Iveco diesels. Against him was fellow Italian Renato della Valle in Ego Lamborghini , an aluminium-hull craft powered by two ear-splitting 800hp, race-tuned V12 Lamborghinis.

Article continues below…

Test driving the Sunseeker Hawk 38 prototype with Fabio Buzzi

Lamborghini boat: tecnomar delivers first official ‘fighting bull’ branded yacht.

Victory went to Buzzi who, after the 157-mile Dundee-Whitby leg, during which White Iveco averaged a staggering 69 knots, dismissed it with shrug saying: ‘In Italy, this is just a cruising boat.’

The race was revived in 2008 attracting a field of 47 raceboats old and new, including a number of production RIBs and sportsboats from companies like Scorpion , Goldfish and Scanner. The favourites included Fabio Buzzi again in his classic four-engined Red FPT , and Austrian casino millionaire Hannes Bohinc in another Buzzi-designed monohull Wettpunkt .

This time the overall winner was a Greek entry Blue FPT navigated by Britain’s Dag Pike, who at 75 years old, was the event’s oldest competitor. Many of the production boats also did remarkably well, showing just how far they have come in recent years.

Steve Curtis MBE is powerboat racing royalty

3. Powerboat racer Steve Curtis

If the Cowes-Torquay-Cowes is the benchmark, surely the top driver must be found among its winners? Home-grown contenders must include Tommy Sopwith, a winner in 1961, 1968 and 1970 and the Gardner brothers, Charles and Jimmy, who clocked up victories in 1964 with their Bertram 31 Surfrider , and again in 1967 in the iconic Sonny Levi-designed Surfury .

On the worldwide stage, Italy’s Renato Della Valle won four Cowes Torquay Cowes races in a row from 1982 to 1985. Hannes Bohinc collected the trophies in 1995 and 2003 and another German, Markus Hendricks, whose boat sank on the 2008 Round Britain, took a re-engined 34-year-old monohull, Cinzano , to victory in 2009 and 2011.

They are all brilliant in their way but how could this category ignore the UK’s Steve Curtis MBE, owner of Cougar Marine, with no fewer than eight Class One powerboat racing world championships in fearsome 175mph catamarans? Curtis’s 2016 victory in the roughest ever Cowes Torquay Cowes race, in a 30-year-old aluminium boat sealed his place in the history books.

4. Lady Violet Aitken – the first lady of fast

The field of legendary female powerboat racers may be smaller but is no less worthy for it with three principal candidates – two titled British ladies and an American grandmother.

From the USA, Betty Cook – focussed, smart, and tough – arrived with her 36ft Cigarette Kaama and blew away the opposition in the 1978 Cowes Torquay Cowes race. She went on to secure two world championships.

The British aristocracy provides the eccentric and brave Countess of Arran, who fielded fast if unconventional designs of three-pointers like Highland Fling among others. She was described by The Guardian in her obituary as ‘beautiful, vivacious, funny, fun and entrancing’.

But our top female driver is Lady Violet Aitken, wife of Cowes-Torquay founder Sir Max Aitken and Ladies’ Trophy winner on several occasions. Racing is still in the blood as her daughter Laura and granddaughter Lucci are both keen powerboat racers.

Buzzi’s legendary status stems from 40 years of work in the marine industry

5. Powerboat designer Fabio Buzzi

The late Fabio Buzzi is a legend, both behind the helm and at the drawing board. In more than 40 years of activity, his company FB Design has won a staggering 52 world championships; seven Harmsworth Trophies; two Round Britains; and set no less than 56 world speed records in both European and American classes.

Buzzi designed the boat that has won more races than any other powerboat in history, the quadruple-engined, be-winged 44ft Cesa/Gancia dei Gancia . Today, the descendants of these monohull designs are found in service with government and military agencies all around the world, as well as leisure craft like the Sunseeker XS2000 and Hawk 38 .

But the competition is hard-fought. Sonny Levi’s delta-shaped race-boats A’Speranziella , Merry-go-Round , Alto Volante , and Surfury leave lasting memories by their sheer performance and poise. And their legacy, the Levi Corsair, is still made today.

The UK’s Don Shead also runs Buzzi close having designed ten Cowes-Torquay winners and the 1984 Round Britain race winner. The early Sunseeker ranges also came from his drawing board.

Peter Thornycroft and Alan Burnard merit attention as designers of the iconic Nelson and Fairey hulls respectively, many of which are still in service today. But the sheer scale of Fabio’s achievements trumps them all.

The Mercury V8 took powerboating to another level

6. The Mercury V8 engine

Early racers only had American petrol V8s for choice, mainly Ford Dearborn Interceptors, tweaked to deliver big torque and 300-400bhp. There were also a few marinised Jaguar straight-six engines, which consumed oil at a terrifying rate and were fragile. Then Carl Kiekhaefer, head of US outboard giant Mercury, refined numerous Mercury Racing V8s and Lamborghini V12s providing up to 850bhp and things took off. Literally.

To this market came car racing engineers Ilmor in the 1990s with a tuned Dodge Viper V10 engine, pushing out a reliable 700-800bhp. The Italians, at the behest of Fabio Buzzi, developed the 16-litre 1,000hp Seatek diesel for ultra-marathon events, providing unparalleled torque with (relatively) light weight and reliability.

A special mention for the maddest motors must go to Tommy Sopwith, who put a pair of helicopter turbines into a 44ft Don Shead hull delivering over 1500bhp and Domenico Achilli, who ‘glued’ two Subaru flat-four rally car engines together, and split our eardrums while winning the 1990 Cowes Torquay Cowes race.

But for sheer consistency and the countless number of ever-faster, smoother, more reliable production engines its powerboat racing successes have spawned, Mercury and its big displacement V8s have to take the crown.

Offering horizontal thrust and reduced drag, the sterndrive greatly increased the speed and efficiency of both race and pleasure craft

7. The sterndrive unit

Early shaft-driven race-boats normally placed engines amidships with straight shafts to the propellers. Then the vee-drive option enabled engines to be moved astern for better weight distribution but, in both cases, the angle of thrust was still pushing the hull ‘uphill’.

With the arrival of the sterndrive came horizontal thrust to harness the growing power of engines, and hugely reduced hydrodynamic drag by doing away with separate rudders, shafts and P-brackets. This greatly increased both speed and efficiency while the ability to trim the angle of thrust also enabled drivers to adjust the boat’s trim to suit differing sea conditions.

Surface-drives from Arneson and Trimax reduced drag even further but at the cost of low speed manoeuvrability and we mustn’t overlook the impact of the outboard engine on both race and leisure sportsboats.

However, for sheer versatility, the impact it has had on both powerboat racing and leisure craft, and its ability to work equally well with both petrol and diesel engines, the sterndrive has to take it.

Hunt’s deep-vee design proved a powerboat game-changer

8. Racing hull designer Ray Hunt

The most successful hull builders embraced the fast-developing world of engineering and materials as well as developments in design. Cold-molded mahogany plywood gave way to GRP, which in turn surrendered to carbon-fibre reinforced by Kevlar.

However, it’s hard to think of a bigger leap in hull design than Ray Hunt’s deep-vee concept, demonstrating an immediate and staggering superiority over previous hard and rounded chines. Nothing underpins this assertion better than Dick Bertram’s 1961 Miami-Nassau victory in his prototype Moppie – finishing a whole day ahead of the third-placed boat.

The likes of Levi, Shead and Bertram all helped refine the concept but the winner has to be Ray Hunt who, along with Dick Bertram’s investment and encouragement, became the grandfather of today’s sportsboats.

Peter Dredge skims Vector Martini to an average speed of 94.5mph during the 2015 Cowes Torquay Cowes race. Photo: Alamy

9. Speed record breaker Peter Dredge

World Water Speed records set by the likes of Donald Campbell’s Bluebird and Richard Branson’s Virgin Atlantic Challenger II are momentous achievements in their fields but their designs have bred few, if any, current sportsboats. Offshore powerboat racing records may not be as well publicised but are arguably far more relevant.

The average speed records of historic races like the Cowes Torquay Cowes race are a perfect demonstration of the improvements made in powertrains, hull design and strength. The first race in 1961 was won by a 24ft wooden Christina averaging 24.5mph. It took another two years to break 40mph, and a further four to exceed 50mph. In 1969 the record tumbled again with an average speed of over 60mph.

A gap of six years then ensued before the record climbed over 70mph and a further 13 years for technology to reach an average exceeding 80mph. A very calm race in 1990 saw the Italians hit over 90mph average – and then we waited 25 years before that speed was finally exceeded in 2015.

So until that record is beaten, preferably with a speed of more than 100mph, our winner is the current record holder Peter Dredge who propelled the awesome 1,500bhp, 44ft Vector Martini to victory at a remarkable average speed of 94.5mph.

Dag Pike, the brains behind so many great powerboat victories

10. National treasure Dag Pike

No top ten list could be complete without mention of those quiet but significant contributors to the sport of offshore powerboat racing. Among those names must be Class-3 racer, commentator, sport historian and MBY ’s longest-serving contributor Ray Bulman, who passed away last year .

The racer, organiser, enthusiast and flamboyant, chain-smoking Tim Powell also has to be in the running. Other characters like Commander Petroni of Italy’s Tornado Racing Team and Tommy Sopwith’s regular crew Charles de Selincourt, who guided him to victory in several Cowes Torquay Cowes races also deserve mentions.

But my National Treasure award goes to Dag Pike; writer, raconteur and navigator extraordinaire who has been the brains behind countless race wins for dozens of different drivers. Having been shipwrecked eight times himself but also having rescued more than eight people in his long career offshore, he has in his own words ‘balanced the books’.

The last word

As with any top ten list it can never be comprehensive and will always be open to differences of opinion but that’s not the point of this article. We simply invite you to ponder that, whatever boat you drive and whatever propels it, its performance and seaworthiness possesses at least some of the DNA of the many great raceboats, designers, engineers and technologies, forged in the heat of offshore battle.

First published in the June 2019 issue of Motor Boat & Yachting.

Navan S30 & C30 tour: Exceptional new Axopar rival

Axopar 29 yacht tour: exclusive tour by the man behind it, mayla gt first look: speed machine with outrageous looks, latest videos, galeon 440 fly sea trial: you won’t believe how much they’ve packed in, parker sorrento yacht tour: 50-knot cruiser with a killer aft cabin, yamarin 80 dc tour: a new direction for the nordic day cruiser.

The World Unlimited water speed record is the officially recognised fastest speed achieved by a water-borne vehicle. The current record of 511 km/h (317 mph) was achieved in 1978.

From 1909 to 1927 the record was an unofficial listing from the organisers of powerboat races.

In 1928 the record category was officially established.

From 1930 the rules of the record stipulated that a craft must make two runs over a timed kilometre course in opposite directions, with the record being the average speed of the two runs.

The record is currently ratified by the Union Internationale Motonautique (UIM).

With an approximate fatality rate of 50%, the record is one of the sporting world's most hazardous competitions.

Beginning in 1908, Alexander Graham Bell and engineer Frederick W. "Casey" Baldwin began experimenting with powered watercraft. In 1919, with Baldwin piloting their HD-4 hydrofoil , a new world water speed record of 70.86 mph was set on Bras d'Or Lake in Nova Scotia.

During the 1920s powerboat racing was dominated by American businessman and racer Gar Wood , whose Miss America boats were capable of speeds approaching 160 kilometers per hour (100 mph). Increased public interest generated by the speeds achieved by Wood and others led to an official speed record being ratified in 1928. The first person to try a record attempt was Gar Wood’s brother George. On 4 September 1928 he drove Miss America VII to 149.40 km/h (92.83 mph) on the Detroit River. The next year Gar Wood took the same boat up a waterway Indian Creek, Miami and reached 149.86 km/h (93.12 mph).

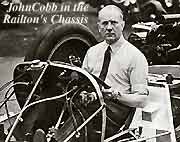

John Cobb - 1900-1952

Like the land speed record , the water record was destined to become a scrap for national honour between Britain and the USA. American success in setting records spurred Castrol Oil chairman Lord Wakefield to sponsor a project to bring the water record to Britain. Famed land speed record breaker and racing driver Sir Henry Segrave was hired to pilot a new boat called Miss England. Although the boat wasn’t capable of beating Gar Wood’s Miss America, the British team did gain experience that they put into an improved boat. Miss England II was powered by two Rolls-Royce aircraft engines and seemed capable of beating Wood’s record.

On July 13, 1930, Segrave drove Miss England II to a new record of 158.94 km/h (98.76 mph) average speed during two runs on Windermere, in Britain’s Lake District. Having set the record, Segrave set off on a third run to try to improve the record further. Unfortunately during the run, the boat struck an object in the water and capsized, with both Segrave and his co-driver receiving fatal injuries.

Following Segrave’s death, Miss England II was salvaged from the lake and repaired. Another racing driver, Kaye Don, was chosen as the new driver for 1931. However, during this time Gar Wood recaptured the record for the US at 164.41 km/h (102.16 mph). A month later on Lake Garda, Don fought back with 177.387 km/h (110.223 mph). In February 1932, Wood responded, nudging the mark up by 1.6 km/h (1 mph).

In response to the continued American challenge, the British team built a new boat, Miss England III . The design was an evolution of the predecessor, with a squared-off stern and twin propellers being the main improvements. Don took the new boat to Loch Lomond in Scotland , on July 18, 1932, improved the record first to 188.985 km/h (117.430 mph), and then to 192.816 km/h (119.810 mph) on a second run.

Miss England II driven by Kaye Don

Determined to have the last word over his great rival, Gar Wood built another new Miss America. Miss America X was 12 metres long, and was powered by four supercharged Packard aeroplane engines. On September 20, 1932, Wood drove his new monster-boat to 200.943 km/h (124.860 mph). It would prove to be the end of an era. Don declined to attempt any further records, and Miss England III became a museum piece. Wood also opted to scale-down his involvement in racing and returned to running his businesses. Somewhat ironically, both of the daredevil record-breakers would live to their 90s. Wood died in 1971, and Kaye Don in 1985.

Boat design changes

Wood’s last record would be one of the final records for a conventional, single-keel boat. In June 1937, Malcolm Campbell , the world-famous land speed record breaker, drove Bluebird K3 to a new record of 203.31 km/h (126.33 mph) at Lake Maggiore. Compared to the massive Miss America X, K3 was a much more compact craft. It was 5 metres shorter and had one engine to X's four. Despite his success, Campbell was unsatisfied by the relatively small increase in speed. He commissioned a new Bluebird to be built. K4 was a ‘three pointer’ hydroplane. Unlike conventional powerboats, which have a single keel, with an indent, or ‘step’, cut from the bottom to reduce drag, a hydroplane has a concave base with two floats fitted to the front, and a third point at the rear of the hull. When the boat increases in speed, most of the hull lifts out of the water and runs on the three contact points. The positive effect is a reduction in drag and an increase in power-to-weight ratio - the boat is lighter as it doesn’t need many engines to push it along. The downside is that the three-pointer is much less stable than the single keel boat. If the hydroplane’s angle of attack is upset at speed, the craft can somersault into the air, or nose-dive into the water.

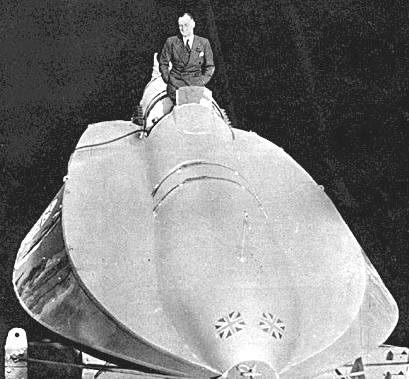

John Cobb's Crusader jet powered WSR boat

Campbell’s new boat was a success. In 1939, on the eve of the Second World War, he took it to Coniston Water and increased his record by 18 km/h (11 mph), to 228.11 km/h (141.74 mph). The return of peace in 1945 brought with it a new form of power for the record breaker – the jet engine . Campbell immediately renovated Bluebird K4 with a De Havilland Goblin jet engine. The result was a curious-looking craft, whose shoe-like profile led to it being nicknamed ‘The Coniston Slipper’. The experiment with jet-power was not a success and Campbell retired from record-attempts. He died in 1948.

1950s. Slo-Mo-Shun and Bluebird: Propriders to Turbojets

Early in the morning of June 26, 1950, a small red boat skipped across Lake Washington, near Seattle, and improved on Campbell’s record by 29 km/h (18 mph). The boat was called Slo-Mo-Shun-IV , and it was built by Seattle Chrysler dealer called Stanley Sayres. The piston-engined boat was able to run at 160 mph because its hull was designed to lift the top of the propellers out of water when running at high speed. This phenomenon, called ‘prop riding’, further reduced drag.

In 1952, Sayres drove Slo-Mo-Shun to 287.25 km/h (178.49 mph) - a further 29 km/h (18 mph) increase. The renewed American success persuaded Malcolm Campbell’s son Donald , who had already driven Bluebird K4 to within sight of his father’s record, to make a push for the record. However, the K4 was completely out-classed and Campbell could not run at the speeds of the Seattle-built boat. In 1951 K4 was written-off when it hit a submerged object on Coniston.

[Left] Sir Malcolm Campbell and the K3 original Rolls Royce Merlin engined superstructure, and [Right] the re-bodied jet engined "slipper" Bluebird K4 .

At this time, yet another land speed driver entered the fray. Englishman John Cobb , was hoping to beat 320 km/h (200 mph) in his jet-powered, all-aluminium built Crusader. A radical design, the Crusader reversed the ‘three-pointer’ design, placing the floats at the rear of the hull. On September 29, 1952, Cobb tried for a 320 km/h (200 mph) record on Loch Ness. Travelling at an estimated speed of 386 km/h (240 mph), Crusader' s front plane collapsed and the craft instantly disintegrated. Cobb was rescued from the water but died of shock soon afterward.

Two years later, on October 8, 1954, another man would die trying for the record. Italian textile magnates Mario Verga and Francesco Vitetta, responding to a prize offer of 5 million lire from the Italian Motorboat Federation to any Italian who break the world record, built a sleek piston-engined hydroplane to claim the record. Named Laura , after Verga’s daughter, the boat was fast but unstable. Traveling across Lake Iseo at close to 306 km/h (190 mph), Verga lost control of Laura , and was thrown out into the water when the boat somersaulted. Like Cobb, he died of shock.

Following Cobbs death, Donald Campbell started working on a new Bluebird - K7, a jet powered hydroplane. Learning the many lessons from Cobb’s ill-starred Crusader , K7 was designed as a classic 3 pointer with sponsons forward alongside the cockpit.

The 26ft long, 10ft wide, 5 ft high, 2.5 ton craft was designed by Ken and Lewis Norris in 1953-54 and was completed in early 1955. It was powered by a Metropolitan-Vickers Beryl turbojet of 3500lbs thrust. K7 was of all metal construction and proved to have extremely high rigidity.

Campbell and K7 set a new record of 325.60 km/h (202.32 mph) on Ullswater in July 1955. Campbell and K7 went on to break the record a further six times over the next nine years in the USA and England (Lake Coniston), finally increasing it to 444.71 km/h (276.33 mph) at Lake Dumbleyung in Western Australia in 1964. Donald Campbell thus became the most prolific water speed record breaker of all time.

Donald Campbell in Bluebird K7

Donald Campbell arrived back at Coniston Water, scene of previous triumphs, in November 1966. Bluebird K7 had been re-engined with a Bristol-Siddeley Orpheus jet rated at 4500lbs thrust. His stated aim was to bump the record out of reach of the Americans, and push it beyond 300mph (480kph) The new attempt suffered many setbacks both mechanical, and weather related, and time by the end of 1966, Campbell existing 276mph record was still not broken. On the morning of January 4, 1967, he was a man under pressure, but the day dawned still, and conditions seemed perfect.

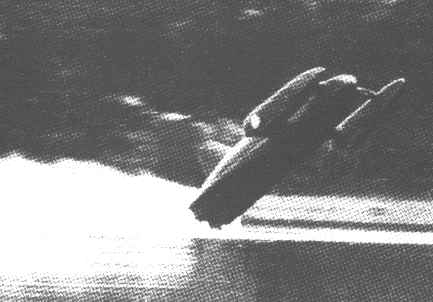

Bluebird K7 was over a decade old, and an American called Lee Taylor was threatening the record with a new boat, Hustler. The patriotic Campbell desperately wanted a Briton to be the first to break 480 km/h (300 mph). His first run across the lake was untroubled and fast. K7 averaged 475.2 km/h (297.6 mph). A new record seemed in sight. Campbell applied K7's water brake to slow the craft down from her peak speed of 315mph as she left the measured Kilo. The wake caused by the water brake was very large from traveling at such high speeds, so Campbell would normally refuel and wait, before starting the mandatory return leg, for the lake to settle again. This time, perhaps fearing that conditions would deteriorate if he waited, Campbell immediately turned around at the end of the lake and began his return run, to try and beat his own wash. Bluebird came back on her return even faster. At around 512 km/h (320 mph), just as she entered the measured Kilo, Bluebird met its wake from the first run. The boat began to lose stability, and finally, 100m before the end of the Kilo, its nose lifted at a 45 degree angle. The boat took off, somersaulted and then plunged nose-first into the lake, breaking up as she cart-wheeled across the surface. Campbell was killed instantly. Prolonged searches over the next two weeks located the wreck, but it was not until May 2001 that Campbell's body was finally located and recovered. Campbell was laid to rest in the churchyard at Coniston on the 12 September 2001

Lee Taylor, a Californian boat racer, had first tried for the record in April 1964. His boat Hustler was similar in design to Bluebird K7, being a jet hydroplane. During a test run on Lake Havasu Taylor was unable to shut down the jet and crashed into the lakeside at over 100mph. Hustler was wrecked and Taylor was severely injured. He spent the following years recuperating, and rebuilding his boat. On June 30, 1967 on Lake Guntersville, Taylor and Hustler tried for the record, but the wake of some spectator’s boats disturbed the water, forcing Taylor to slow down his second run, and he came up 3.2 km/h (2 mph) short. He tried again later the same day and succeeded in setting a new record of 459 km/h (286.875 mph).

Bluebird K7 crash 4 January 1967 - Click picture for video

1970s to the present

Until November 20, 1977, every official water speed record had been set by an American or Briton. That day Australian Ken Warby broke the Anglo - American domination when he piloted his Spirit of Australia to 464.5 km/h (290.313 mph) to beat Lee Taylor’s record. Warby, who had built the craft in his back yard, used the publicity to find sponsorship to pay for improvements to the Spirit. On October 8, 1978 Warby travelled to Blowering Dam, Australia , and broke both the 480 km/h (300 mph) and 500 km/h barriers with an average speed of 510 km/h (318.75 mph).

As of 2005, Warby’s record still stands, and there have only been two official attempts to break it.

Lee Taylor tried to get the record back in 1980. Inspired by the land speed record cars Blue Flame and Budweiser Rocket , Taylor built a rocket-powered boat, Discovery II . The 40-foot long craft was a reverse three-point design, similar to John Cobb’s Crusader , albeit of much greater length.

Originally Taylor tested the boat on Walker Lake in Nevada but his backers demanded a more accessible location, so Taylor switched to Lake Tahoe. An attempt was set for November 13, 1980, but when conditions on the lake proved unfavourable, Taylor decided against trying for the record. Not wanting to disappoint the assembled spectators and media, he decided to do a test run instead. At 432 km/h (270 mph) Discovery II hit a swell and one of the floats collapsed, sending the boat plunging into the water. Taylor’s body and his destroyed craft were never recovered.

In 1989, Craig Arfons, nephew of famed record breaker Art Arfons, tried for the record in his all- carbon-fibre Rain X Challenger , but died when the hydroplane somersaulted at 483 km/h (301.875 mph).

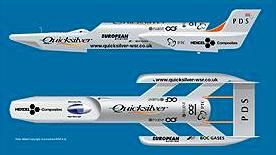

Despite the high fatality rate, the record is still coveted by boat enthusiasts and racers. Currently there are three major projects aiming for the record. The British Quicksilver [1] , The American Challenge project [2] , and spurred into action by the new challengers, Ken Warby has also built a new boat [3] .

In 2001, Bluebird K7 was raised from Coniston Water by members of the Bluebird Project .

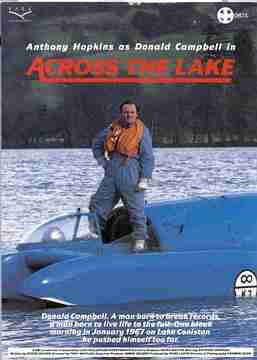

Anthony Hopkins plays Donald Campbell

RECORD HOLDERS

Quicksilver - early drawing

Quicksilver is designed to reach 400 mph (640 km/h). But because the lake only provides a five-mile (8 km) run, it will be difficult to go beyond 325-330 mph (520-530 km/h).

Quicksilver - early model

Nigel Macknight, initiator of the Quicksilver project, is the man who'll be at the controls of the multi-million pound supereboat for the record bid. Nigel has been guided by his mentor, Ken Norris, following the same path Ken mapped out for Richard Noble and Thrust 2, which took the land speed record in 1981.

Originally from Corbridge in Northumberland, Nigel became a professional writer at the age of 21. His first article to appear in print was Speed Kings , an account of the record-breaking exploits of Sir Malcolm and Donald Campbell.

Quicksilver design concept

Speed: 400 mph

Engine: Rolls-Royce Spey 101 turbofan

Thrust: 11,030 lbs

Construction: high tensile steel tubing, honeycomb panels

Nigel MacKnight

Simulations

Nigel MacKnight and Quicksilver

Seven Technical Partners are providing approximately £1million sponsorship in cash and kind. In addition, 26 Technical Associates are providing approximately £0.5 million sponsorship in cash and kind. Over £350,000 cash has been injected by sponsors, supporters and shareholders to date

Other elements manufactured, but not fitted to Quicksilver at the moment, include the cockpit instrument panel and the (pitot-type) airspeed measurement and indicator system (ASI)

Later this year, more work will be done to complete Quicksilver's on-board systems, under the overall direction of Dr. John Challans. Then, the specification of the craft's hull and sponsons will be upgraded so that the first trials on water can begin. In this initial waterborne form, the craft will be known as Quicksilver Dash 1.

Fred Harris and Mike Rimmer (2001). Skimming the Surface .

Kevin Desmond (1996). The World Water Speed Record . Batsford.

Leo Villa (1969). The Record Breakers . Hamlyn.

British challenger Nigel MacKnight

John Cobb and Crusader on Loch Ness

TRANSIT EXAMPLES - The above table illustrates one of the most likely ocean awareness expedition routes showing the time elapsed in days for 7 knots average cruising speed, including times for 5 and 6 knot averages - allowing for 10% downtime and 36 days in ports. Hence, although the objective is to reduce the current solar circumnavigation record from 584 days, the event in not an outright non-stop yacht competition in the offshore racing sense. It remains to be seen how accurate such a prediction might be.

UK VEHICLE INSURANCE ONLINE A - Z

No matter what car, van or bike you drive, we're all looking for great value and quality in our UK motor insurance? But who is the best - who is the cheapest and who offers the great service in the event of a claim?

See the insurance companies below who claim to offer competitive cover at sensible prices, our guide to the jargon and tips for cutting your quote - Good Luck:-

Electric boats

World record, world top speed record for electric powerboat shattered by university team.

Princeton University’s Electric Speedboat team has set a new world water speed record for an electric-powered boat, reaching an average speed of 114 mph (183 km/h or 99 knots) on Lake Townsend near Greensboro, North Carolina.

The record-smashing attempt was made yesterday on the American Power Boat Association’s sanctioned kilo course, breaking the previous record of 88.61 mph set by Jaguar Vector’s race boat in 2018.

The team, comprising over 30 students and alumn i from Princeton University in New Jersey, embarked on this record-breaking journey with a well-prepared strategy and a robustly designed boat. The team used a 150 kW (200 hp) three-phase AC motor attached to a customized D-Stock hydroplane boat.

Capitalizing on the day’s perfect lake conditions, the team took to the course surrounded by the scenic beauty of fall trees.

John Peeters, a renowned hydroplane driver with numerous records under his belt, was at the helm during the feat. Peeters managed an impressive single direction speed of 111 mph. Without stopping to recharge the boat’s batteries, he then pushed even harder in the opposite direction, reaching a speed of 117 mph. The two speeds were averaged together, resulting in the new world record of 114 mph.

Peeters shared his thoughts after the achievement:

“We came together as a team with a dream. Today the hard work and ingenuity brought this dream into a reality. Rarely can one say, we are the greatest or best, but today we can say – fastest electric boat ever.”

The team’s victory came with its own set of challenges. It was discovered post-race that the only propeller shaft they had on hand was broken during the record run, preventing further attempts that day. Despite this setback, the team is optimistic and already looking ahead. Andrew Yates, Princeton Electric Speedboating’s Chief Technology Officer, revealed that after repairs are made, they aim to reach 120 mph in their next attempt, further pushing the boundaries of electric boat speed records.

Electric boats have seen a number of new records set over the last few years. Vision Marine became the first electric boat t o break 100 mph just over a year ago, though the attempt didn’t include a two direction run and thus didn’t unseat Jaguar Vector’s 2018 title broken yesterday by Princeton’s team.

In the endurance world, Candela recently smashed the 24 hour distance record by covering 420 nautical miles in under a day.

FTC: We use income earning auto affiliate links. More.

Micah Toll is a personal electric vehicle enthusiast, battery nerd, and author of the Amazon #1 bestselling books DIY Lithium Batteries , DIY Solar Power, The Ultimate DIY Ebike Guide and The Electric Bike Manifesto .

The e-bikes that make up Micah’s current daily drivers are the $999 Lectric XP 2.0 , the $1,095 Ride1Up Roadster V2 , the $1,199 Rad Power Bikes RadMission , and the $3,299 Priority Current . But it’s a pretty evolving list these days.

You can send Micah tips at [email protected], or find him on Twitter , Instagram , or TikTok .

Micah Toll's favorite gear

Lectric XP 3.0 e-bike sale

Best $999 electric bike ever!

Rad Power Bikes sales

Great e-bikes at great prices!

P1 Offshore;

Powerboat P1 is the fastest growing marine motorsport series in the world and has a long term commitment to growing and developing the sport of power boating at all levels. The Powerboat P1 team works closely with the sports governing bodies, the UIM, APBA and the IJSBA. P1 has delivered more than 85 world championship events in over twelve different countries for more than a decade.

Cookie Policy

Contact info.

- Address: 2320 Clark Street, Suite A1 Apopka, FL 32703 United States

- Phone: +1 407 985 1938

- Email: [email protected]

Cocoa Beach

Fri 17 - Sun 19, May

Lake of the Ozarks

Thu 30, May - 01, Jun

Fri 09 - Sun 11, Aug

Fri 13 - Sun 15, Sep

St. Petersburg

Fri 18 - Sun 20, Oct

222 Offshore Receive Sam Griffith Trophy In Monaco

The 222 Offshore team travelled to Monaco on Saturday to receive the Sam Griffith Trophy awarded to the UIM Class 1 world champions. Australian driver Darren Nicholson and Italian throttleman Giovanni Carpitella were presented with the famous memorial trophy at the 2023 UIM Champions Trophy Ceremony by UIM President Raffaele Chiulli and Powerboat P1 CEO Azam Rangoonwala. Fought out over six races at five events – with a mid-term schedule of back-to-back race weekends and three races in a Continued

Alex Pratt Returns To Class 1 With dfYOUNG

+ Pratt to join owner/throttleman Rich Wyatt as driver for upcoming season + New pairing aiming to improve on dfYOUNG’s third place championship finish in 2023 + Testing in the Sarasota-based 50-foot Mystic sponsored by Good Boy Vodka to start this month The dfYOUNG team competing in this season’s UIM Class 1 World Championship will have a ... Continued

Sheboygan Honored As APBA Best Race Site 2023

The city of Sheboygan in Wisconsin has received the 2023 American Power Boat Association Best Race Site Award for hosting the inaugural Mercury Racing Midwest Challenge in August last year. Designed to acknowledge excellence and improve relationships with race sites, the award recognises and salutes the best venues and organisations supporting APBA-sanc ... Continued

Bally Sports P1 Offshore Broadcast Times For February

Please see below the TV broadcast dates/times for Bally Sports for Powerboat P1 Races ... Continued

29 Jan 2024

Myco trailers continues its partnership with powerboat p1 in 2024.

Long-standing relationship gives MYCO exposure through P1’s race events, television broadcasts, marketing and PR programs ... Continued ...

12 Jan 2024

Powerboat p1 adds lake of the ozarks to 2024 race calendar.

+ Rebranded Shootout Offshore event confirmed for the end of May + P1 race events to be part of the APBA national championship + Class 1 teams to race in Missouri in second round of UIM World Championship Powerboat P1 today announced that it ... Continued ...

09 Jan 2024

Powerboat p1 unveils 2024 p1 offshore and class 1 race calendar.

+ P1 race events to be part of the APBA national championship + New end of season dates for Sarasota and St. Pete grand prix + Mercury Racing event to return to Sheboygan after 2023 success Powerboat P1 has today announced its P1 O ... Continued ...

04 Jan 2024

Bally sports p1 offshore broadcast times for january.

Please see below the TV broadcast dates/times for Bally Sports for Powerboat P1 Races ... Continued ...

14 Nov 2023

Key west worlds race no.3 - imposing their will.

Eric Colby, SOTW: Throughout the 42-year history of the offshore powerboat racing world championships, there are tales of teams that finished in the middle of the pack on Sunday but did enough to claim the title because they had done the math to determine where they needed to finish. Then there were those winner-take-all battles in which the numbers didn’t matter because the contenders were all so close coming into the finale. ... Continued ...

12 Nov 2023

Key west worlds race no. 2 - setting the stage for the finale.

Eric Colby, SOTW: There’s an almost inexplicable allure about Key West. Sure, former TV announcer and pro wrestler Stan Lane coined the phrase, “To be the best, you must win Key West,” but the racers take this motto to heart. The combination of the possibility of myriad conditions on the same course and the tightest corner in the famous harbor make the Key West championship arguably the most sought-after trophy in the sport. ... Continued ...

10 Nov 2023

Key west worlds race no. 1 - dominance carries over.

Eric Colby, SOTW: At the first day of competition at the 42nd annual Race World Offshore Key West World Championship presented by Performance Boat Center, the winners in virtually every class put on a superior display of dominance, setting the stage for three days of heated competition in the southernmost city in the United States. ... Continued ...

26 Oct 2023

The power of sports tourism.

When P1 stages a major sports event, the benefits to the local community extend far beyond the racers and spectators, the local economy and tourism receive a massive boost too. Read what the race venues are saying. ... Continued ...

Partnerships at the Heart of the P1 Business

Earlier this year, Powerboat P1 unveiled an array of sponsors and partners for the 2023 race season. It featured a mix of existing and new sponsors from a wide variety of industries – from energy drinks to insurance, from vodka to logistics. ... Continued ...

2023 Season Offshore Review

2023 was a season of great change and growth. The average race entries were up from 55 in 2022 to 64 boats in 2023. It was also a fine season for racing, with a wide range of weather conditions. It was also a season that had a new infusion of young racers, who made an impact from the start. ... Continued ...

- APBA Offshore Championship

- Asia Powerboat Championship

- Australian Offshore

- Bermuda Offshore

- British Offshore Racing

- P1 Offshore

- P1 Superstock

- P1 Superstock US

- Race World Offshore

- Raid Pavia Venezia

- Super Boat International

- UIM Awards Giving Gala

- UIM Class 1

- UIM Marathon

- UIM Pleasure Navigation

- UIM V2 World Powerboat Championship

- UIM XCAT Racing

- UK ThunderCat Racing

- Australian V8 Superboat Championships

- Circuit Powerboat Association

- E1 World Electric Powerboat Series

- F1 Powerboat Championship Series.

- Powerboat GP

- UAE F4 Championship

- UIM OSY400 European Championship

- UIM World Circuit Endurance

- Unlimited Hydroplane Racing

- F1H2O Nations Cup

- P1 AquaX Bahamas World Championship

- UAE Aquabike Championship

- UIM-ABP Aquabike World Championship

Powerboat Racing World

Frode Sundsdal

What is prw.

It’s a powerboat racing website that has covered circuit racing, offshore racing and PWC since 2016. Maintained by The Race Factory based in Norway who have specialists in event planning and promotion, social media, graphic design, and photography. We are currently working on our vision and believe that we can and will make a different in powerboating. We will dedicate our time to produce accurate factual stories and to promote the sport to a wider global audience.

Round Ireland powerboat record

© 2024 Powerboat Racing World.

IMAGES

COMMENTS

An F1 powerboat rounding a buoy. The Formula 1 Powerboat World Championship (also F1) is an international motorboat racing competition for powerboats organised by the Union Internationale Motonautique (UIM) and promoted by H2O Racing, hence it often being referred to as F1H2O.It is the highest class of inshore powerboat racing in the world, and as such, with it sharing the title of F1, is ...

On October 10th, 2020 a revised version of the historic offshore powerboat race known as the "Rum Run" took place off the coast of Southern California. Produ...

Record Date Location Driver Owner Boat (Hull) Engine Speed; WORLD: 1/4 mile - Straightaway: Sep 27, 2014: New Martinsville, WA: Dan Kanfoush: Jim Sechler (coming soon)

The UIM Class 1 World Powerboat Championship (also known as Class 1) is an international motorboat racing competition for powerboats organized by the Union Internationale Motonautique (UIM). It is the premier class of offshore powerboat racing in the world.. Class 1 is considered one of the most spectacular marine motorsports. A Class 1 race-boat has twin inboard 1100hp engines and can reach ...

The F1H2O World Championship is the leading formula in single-seater inshore circuit powerboat racing and was sanctioned by the UIM in 1981. It is a multiple Grand Prix series of eight events taking place in Europe, the Middle East and Asia. Points allocated at each Grand Prix count towards the overall World Championship standings.

The powerboat team aiming for 11 world records. The Allblack Racing team are going after a full 11 offshore ocean endurance long distance and speed records - and you could be part of their crew ...

FPT Industrial is now part of speed record history. Fabio Buzzi, multiple world-champion of Powerboat Racing and CEO of FB Design, has achieved the fastest s...

Nigel Hook and his team set a new Guinness World Record from Key West to Cuba in 1 hour, 18 minutes, and 3 seconds on August 17, 2017. In addition to a coveted Guinness World Record, Hook and his team not only established several APBA and UIM World Records, they are also the first team to ever race to Havana and make it back to Key West on the ...

Powerboat Racing World covers International Jet Ski, Offshore and Circuit Powerboat Racing. Skip to main content. Hit enter to search or ESC to close. Close Search. search. ... when Nigel Hook and Jay Johnson set the UIM world record for fastest time around Catalina Island from the Huntington Beach Pier at 1 hour 19 minutes 28 seconds, in Lucas ...

Powerboat Racing World covers International Jet Ski, Offshore and Circuit Powerboat Racing. Skip to main content. Hit enter to search or ESC to close. Close Search. ... Britain's Sam Whittle broke the UIM F2 World Speed Record on Coniston Water today. He beat the record of 132.18 MPH which was set by his father Keith in 2013 with a speed of ...

Ocean Cup World Speed Record competitions are designed for sea worthy, offshore craft capable of undertaking independent, extended offshore passages in unprotected waters. First recognized as a sport in 1904, offshore powerboat racing began as point-to-point, endurance races frequently spanning hundreds of miles of open ocean. In the mid-1990s ...

9. Speed record breaker Peter Dredge. World Water Speed records set by the likes of Donald Campbell's Bluebird and Richard Branson's Virgin Atlantic Challenger II are momentous achievements in their fields but their designs have bred few, if any, current sportsboats. Offshore powerboat racing records may not be as well publicised but are ...

Class1 offshore powerboat. Offshore powerboat racing is a type of racing by ocean-going powerboats, typically point-to-point racing.. In most of the world, offshore powerboat racing is led by the Union Internationale Motonautique (UIM) regulated Class 1 and Powerboat P1. In the US, offshore powerboat racing is led by the APBA/UIM and consists of races hosted by Powerboat P1 USA.

The World Unlimited water speed record is the officially recognised fastest speed achieved by a water-borne vehicle. The current record of 511 km/h (317 mph) was achieved in 1978. From 1909 to 1927 the record was an unofficial listing from the organisers of powerboat races. In 1928 the record category was officially established.

Sydney to Hobart (18hrs,7mns). 2002 Yamaha supplied us with 2x225hp 4 strokes. We have a total 9 inter-city records. Ozfreeride.com

The record-smashing attempt was made yesterday on the American Power Boat Association's sanctioned kilo course, breaking the previous record of 88.61 mph set by Jaguar Vector's race boat in 2018.

Class 1 is the premier class of offshore powerboat racing in the world and is considered to be one of the most spectacular marine motorsports. A Class 1 race boat has twin inboard 1100hp engines and can reach speeds in excess of 160mph. All boats are limited by a minimum weight of 4,950kg. History. The sport of powerboat racing dates back to ...

The K PRO Hydro class is a class for kids only. The OSY400 class is the USA version of the largest UIM powerboat racing class in the world. K PRO Hydro and OSY400 are restricted to gasoline and oil fuel. The C Service and C Racing classes are based on American built fishing and racing motors from the 1930s to the 1950s.

P1 Offshore is an organisation responsible for a series of world-class powerboat racing competitions. P1 Offshore is operated by Powerboat P1. Classes include: Class 1, Supercat, Superstock, VX, Stock V, Mod V and Bracket Classes 100 - 700 . ... This cookie does not know or record any of your personal information, it merely records which pages ...

Hit enter to search or ESC to close. Close Search. search

Powerboat Racing World. Bjellandveien 15 3170 Vear - Norway. Frode Sundsdal. Owner +47 46 42 77 88 frode(a)powerboatracingworld.com. What is PRW? It's a powerboat racing website that has covered circuit racing, offshore racing and PWC since 2016. Maintained by The Race Factory based in Norway who have specialists in event planning and ...

In powering through the 100-mph barrier and onward to a top speed of 109 mph (175 km/h), the V32 has surpassed the previous speed record for an electric boat of 88 mph (142.6 (km/h), set over 1 km ...