- BOAT OF THE YEAR

- Newsletters

- Sailboat Reviews

- Boating Safety

- Sailing Totem

- Charter Resources

- Destinations

- Galley Recipes

- Living Aboard

- Sails and Rigging

- Maintenance

Storm Tactics for Heavy Weather Sailing

- By Bill Gladstone

- Updated: November 15, 2021

Storm tactics can be roughly defined as the ways to handle a storm once you’re in it. There are several proven choices, all of which intend to keep either the bow or stern pointing toward the waves. No one tactic will work best for all sailboats in all conditions. As skipper, it will be up to you to consider the best approach for your vessel, procure the right equipment, and practice with it before it’s needed.

Here we look at some active storm options that might work when conditions are still manageable and you want to actively control and steer the boat. Crew fatigue is a serious consideration when using active tactics.

Forereaching

Although not often mentioned as a tactic, it can be highly effective for combating brief squalls or moderate-duration storms. Here’s how to set up your boat for forereaching: Roll the jib away (especially if you have a large roller-furler genoa set); reef the main down to the second or third reef position; and sail on a closehauled course, concentrating on keeping the boat flat. It will be a comfortable ride, everyone will be relatively happy, and you will be making 2 to 3 knots on a close reach. Check your course over ground because increased leeway will cause your track to be much lower. This is a possibly useful tactic to claw off a lee shore. Note that not all boats will be at ease forereaching, so you’d better experiment with it ahead of time. Catamarans in particular will lurch and demonstrate much-increased leeway.

Motorsailing

Sometimes it’s necessary from a time or safety perspective to stow the jib and fire up the iron genny instead. Motorsailing lets you point high and make progress to windward. Motoring with no sails will not work well (or at all, in some cases), particularly in big seas, but a reefed mainsail will provide lateral stability and extra power. Trim the main, head up high enough to control your angle of heel, set the autopilot, and keep a lookout. Fuel consumption makes this a short-term option.

Here’s a tip: Make sure cooling water is pumping through the engine. On some sailboats, the water intake lifts out of the water when heeled. A further difficulty is that the pitching boat might stir sediment off the bottom of the fuel tank, which can, in turn, clog the fuel filter.

Running off and drogues

Sailing under storm jib and a deeply reefed mainsail or storm trysail provides the most control. If you don’t have storm sails, a reefed jib will give you the power to steer and control your boat in the waves. The boat must be steered actively to maintain control because no autopilot will be able to do this.

If excessive speed is a problem and steering becomes difficult, towing a drogue will slow the boat. A retrieval line should be set from the head of the drogue for when it is time to bring it back on board. If you don’t have a drogue, trailing warps might help slow the boat.

In a storm of longer duration, or when conditions become otherwise unmanageable, the situation might call for a skipper to consider passive storm tactics. When you are exhausted and you just want to quiet down the boat and maybe get some rest, there are other boathandling options available, depending on the sea state and the equipment you have onboard.

Heaving to can be an excellent heavy-weather tactic, though some boats fare better than others. Wouldn’t it be great if during a heavy-weather episode you could just slow everything way down? Imagine a short respite with a reduced amount of motion from the relentless pitching and pounding. A chance to regroup, make a meal, or check over the boat. Well, you can.

Heaving to allows you to “park” in open water. Hove-to trim has the jib trimmed aback (that is, to the wrong side), the reefed main eased, and the helm lashed down to leeward. The easiest way to do this is to trim the jib sheet hard and then tack the boat, leaving the sheet in place. Trimmed this way, the jib pushes the bow down. As the bow turns off the wind, the main fills and the boat moves forward. With the helm lashed down, the rudder turns the boat toward the wind. As the main goes soft, the jib once again takes over, pushing the bow down. The main refills, and the rudder pushes the bow into the wind again.

RELATED: Safety at Sea: Mental Preparations Contribute to Positive Outcomes

Achieving this balance will require some fine-tuning, depending on the wind strength, your boat design and the sails you have. You might, for example, need to furl the jib most of the way in to match the wind strength. Trimming the main will ensure that the bow is at an angle to the waves, ideally pointing 40 to 60 degrees off. Modern fin-keeled boats do not heave to as well as more-traditional full-keel designs.

When hove to, the boat won’t actually stop. It will lie, as noted, about 40 to 60 degrees off the wind, sailing at 1 or 2 knots, and making leeway (sliding to leeward). Beware of chafe. When hove to, the jib’s clew or sheet will be up against the shroud and might experience wear damage. Monitor this regularly, and change the position of the sheet occasionally. You might not want to heave to for an extended time.

Deploying a sea anchor

A sea anchor is a small parachute deployed on a line off the bow. A sea anchor helps keep the bow pointed up into the waves so the boat won’t end up beam to the seas. Light displacement boats will pitch violently in high seas, and chafe and damage might occur to the bow, so setting up a bridle and leading it aft through a snatch block will allow the boat to lie at an angle to the waves, providing a more comfortable ride. A big concern when using a sea anchor is the load on the rudder as the waves slam the boat backward. Chafe on the sea-anchor bridle is another big factor, so the bridle must be tended regularly.

Remember, if you and your vessel are caught out in heavy-weather conditions, as a skipper, you must show leadership by setting an example, watching over your crew, offering relief and help to those who need it, and giving encouragement. Remember too, discomfort and fear can lead to fatigue, diminished performance, and poor decision-making. Don’t compromise the safety of the boat and crew to escape discomfort.

Few people get to experience the full fury of a storm. Advances in weather forecasting, routing and communications greatly improve your odds of avoiding heavy weather at sea, but you’re likely to experience it at some point, so think ahead of time about the tactics and tools available to keep your crew and vessel safe.

Heavy weather might not be pleasant, but it is certainly memorable, and it will make you a better sailor. Take the time to marvel at the forces of nature; realize that the boat is stronger than you think.

Happy sailing, and may all your storms be little ones!

This story is an edited excerpt from the American Sailing Association’s recently released manual, Advanced Cruising & Seamanship , by Bill Gladstone, produced in collaboration with North U. It has been edited for design purposes and style. You can find out more at asa.com.

- More: Anchoring , How To , print nov 2021 , safety at sea , seamanship

- More How To

How to Keep Your Windlass Working For You

Southern Comfort: Tactical Tips for Sailing South

Preparing to Head Out

Adding Onboard Electronics? Here’s How To Get Started

The Re-creation: My Day at the St. Pete Regatta

Musto’s MPX Impact is Made for Offshore

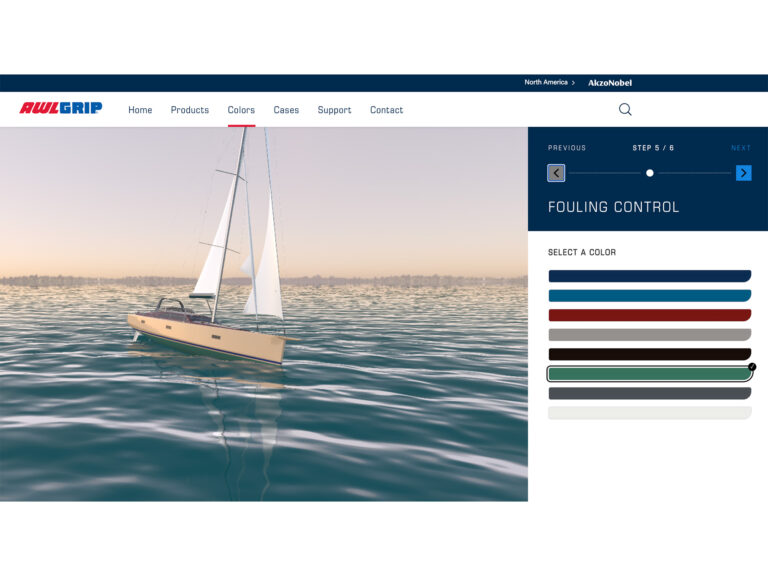

Awlgrip Unveils 3D Color Visualizer

- Digital Edition

- Customer Service

- Privacy Policy

- Email Newsletters

- Cruising World

- Sailing World

- Salt Water Sportsman

- Sport Fishing

- Wakeboarding

- Sail Care & Repair

- Sailing Gear

- Find A Loft

- Sail Finder

- Custom Sails

- One Design Sails

- Flying Sails

- New Sail Quote

- 3Di Technology

- Helix Technology

- Sail Design

- NPL RENEW Sustainable Sailcloth

- Sailcloth & Material Guide

- Polo Shirts

- Sweaters & Cardigans

- Sweatshirts & Hoodies

- Accessories

- Mid & Baselayers

- Deckwear & Footwear

- Luggage & Accessories

- Spring Summer '24

- Sailor Jackets

- Maserati X North Sails

- NS x Slowear

- T-shirts & Tops

- Sailor Jacket

- Sustainability

- North Sails Blog

- Sail Like A Girl

- World Oceans Day

- Icon Sailor Jacket

- Our Locations

- Certified B Corporation

- North SUP Boards

- North Foils

- North Kiteboarding

- North Windsurfing

SAIL FINDER

SAILING GEAR

COLLECTIONS & COLLAB

COLLECTIONS

WE ARE NORTH SAILS

ACTION SPORTS

Popular Search Terms

Collections

Sorry, no results for ""

Subscription

Welcome aboard, welcome to north sails.

Stay up to date with the latest North Sails news.

Receive a 10% discount code for your first apparel order. Excludes sails and SUP’s. See our Terms and Conditions .

Yes, I agree to the terms of use and privacy policy.

HOW TO SAIL SAFELY THROUGH A STORM

Tips and tricks to help you get home safe.

Compared to the quick response and sudden nature of a squall , sailing through a storm in open water is an endurance contest. In addition to big wind, you’ll have to deal with big waves and crew fatigue.

Sailing in Waves

Sailing in big waves is a test of seamanship and steering, which is why you should put your best driver on the helm. Experienced dinghy sailors often are very good at heavy air steering, because they see “survival” weather more often than most cruisers.

Avoid sailing on a reach across tall breaking waves; they can roll a boat over. When sailing close-hauled in waves, aim toward flat spots while keeping speed up so you can steer. To reduce the chance of a wave washing across the deck, tack in relatively smooth water. A cubic foot of water weighs 64 pounds, so a wave can bring many hundreds of pounds of water across the deck.

Sailing on a run or broad reach in big waves is exhilarating, but be careful not to broach and bring the boat beam-to a breaker. Rig a preventer to hold the boom out.

Storm Sails

If reefing isn’t enough to reduce power, it’s time to dig out your storm sails — the storm trysail and storm jib. They may seem tiny, but since wind force rises exponentially, they’re the right size for a really big blow. Storm trysails are usually trimmed to the rail, but some modern ones are set on the boom. The storm jib should be set just forward of the mast to keep the sail plan’s center of effort near the boat’s center of lateral resistance. This helps keep the boat in balance.

Storm Strategy

The first decision before an approaching storm is the toughest: Run for cover, or head out to open water for sea room? With modern forecasting, a true storm will rarely arrive unannounced, but as you venture further offshore the chances of being caught out increase. While running for cover would seem the preferred choice, the danger lies in being caught in the storm, close to shore, with no room to maneuver or run off.

Two classic storm strategies are to try to keep away from land so you’re not blown up on shore, and to sail away from the storm’s path — especially its “dangerous semicircle,” which is its right side as it advances.

Storm Tactics

Storm tactics help you handle a storm once you’re in it. There are several proven choices, all of which aim to reduce the strain and motion by pointing one of the boat’s ends (either bow or stern) toward the waves. No one tactic will work best for all boats in all conditions.

Sail under storm jib and deeply reefed mainsail or storm trysail. This approach provides the most control. Sails give you the power to steer and control your boat in the waves.

Run before the storm with the stern toward the waves, perhaps towing a drogue to slow the boat. This tactic requires a lot of sea room, and the boat must be steered actively. Another concern is that you will remain in front of an approaching storm, rather than sailing out of its path.

Heave-to on a close reach with the jib trimmed to windward. Heaving-to can be an excellent heavy weather tactic, though some boats fare better than others.

Deploy a sea anchor while hove-to or under bare poles. A sea anchor is a small parachute set at the end of a line off the bow. A sea anchor helps keep the bow up into the waves so the boat won’t end up beam to the seas. One concern is the load on the rudder as waves push the boat aft.

Another alternative is lying ahull, simply sitting with sails down. This passive alternative is less reliable than the other tactics, as you lose the ability to control your angle to the waves and may end up beam to the seas. Furthermore, the motion of the boat rolling in the waves without the benefit of sails can be debilitating.

Want to order a storm trysail or storm jib for your boat? Contact a North Sails Expert here .

How to Heave-To

Wouldn’t it be great if, during a heavy air sail, you could just take a break, and relax for a bit? Imagine a short respite from the relentless pitching and pounding: a chance to rest, take a meal, or check over the boat in relative tranquility. Well, you can. The lost art of heaving-to allows you to “park” in open water.

To heave-to, trim the jib aback (i.e., to the wrong side), trim the main in hard, and lash the helm so the boat will head up once it gains steerageway. As the jib tries to push the bow down, the bow turns off the wind and the main fills, moving the boat forward. Once the boat begins to make headway, the lashed helm turns the boat toward the wind again. As the main goes soft the jib once again takes over, pushing the bow down. The main refills, and the rudder pushes the bow into the wind again.

The boat won’t actually stop. It will lie about 60 degrees off the wind, sailing at 1 or 2 knots, and making significant leeway (sliding to leeward). The motion will be much less than under sail, and dramatically more stable and pleasant than dropping all sails and lying ahull. You will also be using up less sea room than if you run before the storm at great speed.

Achieving this balance will require some fine tuning, depending on the wind strength, your boat design, and the sails you are flying. Also, fin-keeled boats do not heave to as well as more traditional designs.

In storm seas, some boats will require a sea anchor off the bow to help hold the boat up into the waves while hove-to.

Alternate Storm Strategy: Don’t Go

If conditions are wrong, or are forecast to worsen, don’t go. If you can avoid the storm, then do so.

If you’re at home, stay there. If you’re mid-cruise, button up the boat, make sure your anchor or mooring or dock lines are secure, and then read a book or play cards. Relax. Enjoy the time with your shipmates. Study the pile of Owners’ Manuals you’ve accumulated with each piece of new gear. Tinker with boat projects.

Put some soup on the stove, and check on deck every so often to make sure the boat is secure. Shake your head as you return below, and remark, “My oh my, is it nasty out there.”

If your boat is threatened by a tropical storm or hurricane, strip all excess gear from the deck, double up all docking or mooring lines, protect those lines from chafe, and get off. Don’t risk your life to save your boat.

Misery and Danger

Although everyone will remember it differently years later, a long, wet, cold sail through a storm can be miserable. As the skipper, you need to make the best of it: watch over your crew, offer relief or help to those who need it, and speak a few words of encouragement to all. “This is miserable, but it will end.”

Take the time to marvel at the forces of nature, and at your ability to carry on in the midst of the storm. Few people get to experience the full fury of a storm. It may not be pleasant, but it is memorable.

While misery and discomfort can eventually lead to fatigue, diminished performance, and even danger, do not mistake one for the other. Distinguish in your own mind the difference between misery and danger. Don’t attempt a dangerous harbor entrance to escape misery; that would compromise the safety of the boat and crew, just to avoid a little discomfort.

Interested in a new sail quote or have questions about your sails? Fill out our Request a Quote form below and you will receive a reply from a North sail expert in your area.

REQUEST A QUOTE

FEATURED STORIES

Lightning tuning guide, offshore sailing guide, how to care for your foul weather gear.

- Refresh page

Yachting World

- Digital Edition

Catamaran Sailing Techniques Part 6: Coping with heavy weather – with Nigel Irens

- Harriett Ferris

- November 10, 2015

Anticipating bad weather is, as in any boat, the best way to prepare for a blow, but if you’re caught out, Nigel Irens has some advice specific to cats

A racing boat that also has access to high-quality weather forecasting data should be able to steer clear of potentially dangerous weather by outrunning it. Performance cruisers with fine bows should be able to surf downwind in all but the most extreme weather, often travelling safely at speeds of 20 knots or more for periods of, say, 10-15 seconds.

But in the same conditions a stubbier, bluff-bowed charter catamaran would soon start feeling dangerous if the crew were pushing too hard under these conditions.

Obviously reducing sail is the first response, but as mentioned earlier in this series, shortening a mainsail in downwind conditions is not really possible without turning head to wind, and if the wind and sea-state are rising then the moment to do that safely may already have passed.

An experienced crew will have anticipated the rising wind and reefed the main a few hours back. Shortening sail forward of the mast is a piece of cake by comparison – especially if all it takes is to let the jib fly and roll up some of the area. Getting rid of an asymmetric might be challenging, but at least it won’t be dangerous.

Being caught with too much sail up along with the knowledge that you’ve missed the chance to round up and reef is not very helpful. You’ve inadvertently got into this situation and you’ve obviously still got to think up some way to get out of it.

Reefing the main

Brute force might provide the get-out-of-jail-free solution for reefing a main downwind in worsening conditions. But this might not be possible as the sail will not drop when you release the halyard because it will be pressing hard against the standing rigging. The luff cars will also be under load from the side (which they are not really designed to be).

If you have left it too late to head up safely, brute force may be the only way to get the main down

The best way forward is to leave the mainsail halyard where it is and sheet the main in until it is no longer pressing against the rigging. Some vang load on the boom will be needed because simply easing the sheet will invite the sail to twist so that it is still hard against the rigging.

The next move is to start loading both the luff and clew reef lines that are ready for hauling in the next reef. When they are bar-tight you can try easing a bit of halyard. If the sail moves that’s good news, but it will only fall a short way before the sail is once again draped over the standing rigging.

It’s only by repeating this process as many times as necessary that the exposed mainsail should end up the size you want it to be. It may be hard work, but who cares if you can feel the relief at getting out of this fix.

Rounding up to reef

If the mainsail still refuses to come down your only remaining option may be to round up. Given that conditions have likely worsened, this may not be very appealing, but careful preparation can help to minimise the stress.

First, ensure that the halyard is flaked and ready to go. You will need one person to focus on this job plus someone on the helm at all times as you cannot afford for the bows to fall away midway through the manoeuvre.

Also, make sure that the reef line(s) is ready to be hauled in, although if things have got this bad and you are expecting worse to come, it may be best simply to drop the mainsail and return to your downwind course as quickly as possible.

If turning upwind to reef, roll up the headsail by about two-thirds to stop it flogging and losing control

If you have a spare pair of hands, make sure someone is available to tail the mainsheet as you come into the breeze to prevent the sheet from flogging violently.

Then, if you can, have someone ready to pull the sail down at the luff. Full length battens on car sliders often mean that the mainsail luff forms tubes when it is lowered, which get inflated with the strong wind and prevent the sail from dropping on its own. The sail may need some help to get it down onto the boom. Make sure that the crewmember tasked with this is clipped on properly and braced ready for the round up into the breeze.

Have the leeward engine running – in neutral is fine – just so that you can give a burst of forward drive if required to keep your steerage and help with a quick bear away once the manoeuvre is complete.

Finally, communication is key. Make sure everyone knows exactly what you are doing and when they need to act. The quicker you can carry out the drop the better – it will be noisy when you head up into the breeze.

Planning for the conditions

It may be that reducing sail is in response to a short-lived squall, after which you’ll be able to make sail again, but if this is the beginning of a more serious blow then you need to have planned what to do as conditions worsen.

You could try sailing under bare poles for a while, but this can feel a little awkward as you may surf quite well down a wave then almost lose steerage way in the troughs, so setting a smidgin of jib will probably feel better as it’s no surprise that being pulled along from the front is more likely to improve steerability than simply being pushed by the wind pressure on the transoms and aft bulkhead.

Either way if the wind continues to rise a time might come when you want to forget about progressing and just render the boat safe while reducing the stress and anxiety of the crew by making things comfortable below.

You might want to remove all sails and proceed under engine

The usual way to achieve this is to set some kind of sea-anchor or drogue, which is designed to do just that, although advising on the right way to go about this is one of those subjects that offers huge scope for deeply entrenched disagreement.

Sea anchors and drogues

The term ‘sea-anchor’ usually refers to a device with an area big enough to hold the boat almost stationary – usually bows on to the seas – whereas a ‘drogue’ is a device intended to slow the boat’s drift downwind.

The consensus among catamaran sailors seems to be that setting a device from the stern works better than from the bow, so the drogue approach is the obvious choice as a full sea anchor tends to hold the sterns down, increasing the risk of taking a tonne of green water in the cockpit.

There are some neat series drogues available now which consist of a strong line with multiple tiny drogues attached to it. That means you effectively have variable power in the ‘braking system’ and can experiment until you get the best result.

Building some confidence in this sort of device through trial and error plays a vital role in preparing to manage real heavy weather. Feeling that you’re on top of this kind of situation also gives you peace of mind.

Staying safe upwind

Staying safe when going upwind is a lot less complicated. To start with if you’re on a standard charter-style catamaran you’d have to be trying pretty hard to get into any serious danger of capsizing.

Deck hardware may be undersized for the obvious reason that it’s a way to limit cost, but it’s also true that anything that makes it hard to power up one of these boats is going to help keep it right-side-up. In any event it soon becomes obvious (through trial and error) that hanging onto too much sail in a rising wind never pays, so reef early and don’t hesitate to press the engine into service.

As the wind rises, don’t put off reefing, shorted sail on the headsail first for control

Reefing is relatively easy upwind, but it’s important to keep the boat moving forward – maybe by keeping the headsail powered up – so you maintain steerage way. If you stop you might get knocked back by a big breaker and that could dig the sterns, which in extreme cases could even result in a stern-first capsize.

More usually, though, avoiding being pushed backwards is more about avoiding rudder damage, which can obviously leave you with a big problem. Starting the leeward engine before reefing (or even tacking) is a good idea just to make sure you can always keep some forward way on and therefore maintain steerage. While strong winds might mean you want to reduce speed, stopping altogether can be just as precarious.

Do’s and don’ts

- DO keep the mainsail area to a minimum when sailing downwind in unpredictable weather.

- DO have a go at reefing downwind, even if conditions don’t call for it. At least you’ll find out how feasible it is, which could be really useful on the day when you’ve been backed into a corner and have to try it for real.

- DO reef early upwind. You’ll probably make better VMG and certainly reduce anxiety on board as the wind rises.

- DON’T trust a stumpy catamaran with high-volume bows. Far from piercing waves downwind it might just trip up if pushed too hard, so don’t push your luck – especially in heavy seas.

- If you’re in a bread-and-butter ‘floating castle’ sort of catamaran DON’T expect miracles upwind. The seamanlike solution often involves applying a bit of engine power.

- DON’T forget that as skipper you’re there to look after the crew, so try not to let fantasies about competing in the Route du Rhum take over. The boat is what it is.

Our eight-part Catamaran Sailing Skills series by Nigel Irens, in association with Pantaenius , is essential reading for anyone considering a catamaran after being more familiar with handling a monohull.

Part 7: Capsize – it’s unlikely, but what to do if the worst should happen

Series author: Nigel Irens

One name stands out when you think of multihull design: the British designer Nigel Irens.

His career began when he studied Boatyard Management at what is now Solent University before opening a sailing school in Bristol and later moving to a multihull yard. He and a friend, Mark Pridie, won their class in the 1978 Round Britain race in a salvaged Dick Newick-designed 31-footer. Later, in 1985, he won the Round Britain Race with Tony Bullimore with whom he was jointly awarded Yachtsman of the Year.

His first major design success came in 1984 when his 80ft LOA catamaran Formule Tag set a new 24-hour run, clocking 518 miles. During the 1990s it was his designs that were dominant on the racecourse: Mike Birch’s Fujicolour , Philippe Poupon’s Fleury Michon VIII , Tony Bullimore’s Apricot . Most famous of all was Ellen MacArthur’s 75ft trimaran B&Q, which beat the solo round the world record in 2005.

His designs have included cruising and racing boats, powerboats and monohulls, but it is multis he is best known for.

See the full series here

A special thanks to The Moorings, which supplied a 4800 cat out of their base in Tortola, BVI. www.moorings.com

A Complete Guide To Sailing In A Storm

Sailing in a storm can be a challenging experience but with the right preparation and techniques, it can be navigated safely in most instances.

While it's best to avoid storms when sailing, there are times when storms cannot be avoided.

To sail in a storm:

- Prepare the sailboat for a storm

- Monitor the weather conditions

- Adjust the sailboat to stabilize the vessel in the storm

- Maintain communication with the coast guard

The number one priority when sailing in a storm is safely navigating through the water during these bad weather conditions.

1. Prepare The Sailboat For A Storm

The first step of sailing in a storm is to prepare the sailboat for storm weather conditions.

To prepare a sailboat for a storm:

- Check the rigging & sails : Assess the rigging and sails overall condition. Ensure they are in full working order with no issues with maneuverability or rips in the sails. There should be a storm sail onboard too in preparation for sailing in the storm

- Ensure safety equipment is onboard : Ensure there are liferafts, life jackets for everyone onboard, life buoys, heaving lines, sailing jackets, flashlights, flares, VHF radios, chartplotter/GPS, first aid kits, and fire extinguishers

- Remove the boat canvas/bimini top : In preparation for sailing in a storm, remove the boat canvas/bimini top to prevent it from getting damaged or destroyed or causing injury to passengers onboard

- Ensure loose items are tied down : Any loose items like lines on the deck should be tied down and secured before sailing in a storm. Loose items can become dislodged and damaged or cause injury to passengers onboard if they are not secured during a storm

- Ensure the sailboat's engine is in great condition : Ensure the sailboat's motor is in perfect condition with sufficient oil and fuel to operate during the storm

Preparing the sailboat for a storm will take approximately 30 minutes to complete. This timeframe will vary depending on the size of the vessel and the amount of equipment needed to be purchased and installed onboard.

In preparing for sailing in a storm, there is certain sailboat equipment needed. The equipment needed for sailing in a storm includes a storm sail, heaving lines, sailing jackets, life jackets, life buoys, liferafts, first aid kit, Chartplotter/GPS, fire extinguishers, VHF radio, and flares.

The benefits of preparing the sailboat for a storm are a sailor will be prepared for any issues caused by the storm and a sailor will have the necessary safety equipment to help keep everyone onboard safe during the storm.

One downside of preparing the sailboat for a storm is it can be costly (over $500) especially if the sailor does not have all the right equipment needed to withstand the stormy weather. However, this is a small downside.

2. Monitor The Weather Conditions

The second step of sailing in a storm is to monitor the weather conditions regularly.

To monitor the weather conditions:

- Connect to the VHF radio weather channel : Connect to channel 16 on the VHF radio as this channel provides storm warnings and urgent marine information for boaters

- Use a chartplotter : Modern chartplotters will have marine weather data for boaters to monitor the weather conditions and check windspeeds, rainfall levels, wave height and other relevant marine weather data

- Check a marine weather forecast provider website : If you have internet access on the sailing trip, connect to a marine weather provider for marine weather forecast information in your area

In sailing, weather conditions are considered a storm when the wind speed is 28 knots or higher and the wave heights are 8ft or higher. Other characteristics of stormy weather when sailing is poor visibility with visibility ranges of under half a mile (0.8km or less) and heavy rain with a precipitation rate of at least 0.1 inches (2.5 millimeters) per hour.

It can take approximately 3 to 6 hours for a storm to fully develop when sailing. However, for larger storms, it can take over 2 days for the storm to fully develop.

Monitoring the weather should be done every 20 minutes when sailing in a storm to get up-to-date information on potential nearby locations with better weather to sail to.

The benefit of regularly monitoring the weather conditions is a sailor will be more prepared for the weather that lies ahead and the sailor will be able to make adjustments to their sailing route to help avoid the bad weather.

3. Adjust The Sailboat To Stabilize The Vessel

The third step of sailing in a storm is to adjust the sailboat to stabilize the vessel.

When sailing through the storm, reef the sails to reduce the stress and load on the mast and sails, attach the storm sails, turn the vessel until the wave and wind direction are blowing from the stern of the sailboat, i.e. the wind is blowing downwind. Carefully tack the sailboat slowly until the boat is in the downwind position. Pointing the sailboat downwind is not recommended if the sailboat is near land as it could cause the boat to run into the land.

Alternatively, if the storm is very bad, sailors can perform a "heaving to" storm sailing maneuver.

To perform the heave-to storm sailing maneuver:

- Turn the bow of the boat into the wind : This involves turning the sailboat so that the bow faces into the wind. This will cause the boat to lose forward momentum and begin to drift backward

- Adjust the sails : Depending on the size and configuration of your boat, you may need to adjust the sails in different ways. In general, you will want to position the sails so that they are catching less wind and are working against each other. This will help to slow the boat's drift and keep it from moving too quickly

- Adjust the rudder : You may need to adjust the rudder to keep the boat from turning too far or too fast. In general, you will want to angle the rudder slightly to one side to counteract the wind and keep the boat on a stable course

- Monitor the boat's drift : Once you have heaved-to, you will need to monitor the boat's drift and make small adjustments as needed to maintain your position. This may involve adjusting the sails, rudder, or other factors as conditions change

The heaving to maneuver is used to reduce a sailboat's speed and maintain a stationary position. This is often done in rough weather to provide the crew with a stable platform to work from or to wait out a storm.

This sailing maneuver will adjust the sailboat and should stabilize the vessel in the storm.

The benefits of adjusting the sailboat position in a storm are it will help to stabilize the boat, it will improve safety, it will reduce the crew's fatigue as the crew will not be operating with a boat at higher speeds, it will help maintain control of the sailboat, and it will reduce stress on the sailboat and the rigging system.

Depending on the size of the sailboat, how bad the weather conditions are, and a sailor's experience level, adjusting the sailboat to stabilize it in the storm should take approximately 10 minutes to complete.

4. Maintain Communication With The Coast Guard

The fourth step of sailing in a storm is to maintain communication with the coast guard.

This is particularly important if the storm is over Beaufort Force 7 when sailing is much harder.

To maintain communication with the coast guard during a storm:

- Understand the important VHF channels : During sailing in a storm, be aware of VHF international channel 16 (156.800 MHz) which is for sending distress signals

- Ensure there are coast guard contact details on your phone : Put the local coast guard contact details into your phone. These contact details are not substitutes for using the VHF channel 16 distress signal or dialing 911. These contact details should only be contacted if all else fails

Contacting the coast guard takes less than 1 minute to complete and they are fast to respond in case of an emergency caused by the storm.

The benefits of maintaining communication with the coast guard during a storm are it will help improve safety, the coast guard will be able to provide real-time alerts, and it will provide navigation assistance as the coast guard has access to the latest navigation technology and can guide you through the storm's hazardous areas such as shallow waters or areas with a strong current.

Frequently Asked Questions About Sailing In A Storm

Below are the most commonly asked questions about sailing in a storm.

What Should You Do If You're Caught Sailing In A Storm With Your Boat?

if you're caught sailing in a storm with your boat, you should reef the sails, attach the storm sails and tack the vessel slowly until the wave and wind direction are blowing from the stern of the sailboat.

Should You Drop An Anchor When Sailing In A Storm?

Dropping an anchor can be a useful technique to help keep a boat steady during a storm. However, whether or not to drop an anchor depends on a variety of factors including the size and type of the boat, the severity of the storm, the water depth, and the type of bottom (i.e., mud, sand, or rock).

If you are in a smaller boat that is being pushed around by the waves, dropping an anchor can help keep the boat oriented in a particular direction, reducing the boat's drift. Additionally, it can help reduce the risk of capsizing or being thrown onto a rocky shore.

However, if the storm is very severe with high winds and waves, the anchor may not be enough to hold the boat in place, and it may put undue stress on the anchor and the boat's attachment points. In such a case, it is usually better to try to navigate to a sheltered area or to deploy sea anchors that can help reduce the boat's drift.

It is also essential to be careful when anchoring in a storm as it can be challenging to set the anchor correctly and the wind and waves can cause the anchor to drag.

Is It Safe To Sail In A Storm?

Sailing in a storm should be avoided due to the lack of safety. However, experienced sailors can sail in storms up to Beaufort Force 7 if required. Beaufort Force 8 and higher storms are extremely dangerous to sail in and should be avoided at all costs.

How Do You Improve Safety When Sailing In A Storm?

To improve safety when sailing in a storm, wear a life jacket, hook everyone onboard up to a safety line or harness so they don't fall overboard, reef the sail to improve the sailboat's stability, and understand where all the safety equipment is onboard and how to operate it in case of an emergency.

What Type Of Storm Should Not Be Sailed In?

A sailor should not sail in any storm but especially a storm from Beaufort Force 8 to Beaufort Force 12 as it is considered to be too dangerous.

Can You Sail Through A Hurricane?

While sailors have successfully sailed through hurricanes in the past, sailing through a hurricane should be avoided at all costs. Sailing in hurricane weather is too dangerous and could result in loss of life.

What Are The Benefits Of Sailing In A Storm?

The benefits of sailing in a storm are:

- Improves sailing skills : Sailing in a storm will force sailors to improve their sailing skills and increase their ability to handle rough seas

- Exciting experience : For some sailors, the thrill of navigating through a storm can be an exhilarating experience that they enjoy. The adrenaline rush and sense of accomplishment of successfully sailing through a storm can be incredibly rewarding

- Greater appreciation for the power of nature : Sailing in a storm can provide a unique perspective on the power of nature. It can be humbling and awe-inspiring to witness the raw force of the wind and waves and this can lead to a greater appreciation for the natural world

It's important to note that these potential benefits should never come at the expense of safety. For the majority of sailors, it is smarter to avoid sailing in a storm and instead wait for the bad weather to pass.

What Are The Risks Of Sailing In A Storm?

The risks of sailing in a storm are:

- Boat sinking/capsizing : With high winds over 28 knots and waves and swells at heights over 8ft, there is a risk of the sailboat capsizing and sinking

- People drowning : High winds and high waves during a storm can cause people onboard to fall overboard and drown

- Loss of communication : Bad storm weather can cause the sailboat's communication system to stop working making it much harder to signal for help if needed

- Boat damage : Storm weather can damage the boat including the sails, mast, rigging system, lines, Bimini top, etc.

- Poor visibility : Sea spray, large waves over 8ft, and heavy winds over 28 knots can reduce the visibility to under 500 meters in some instances making it difficult for navigation

- People being injured : People onboard can get injured due to the increase and sharp movements caused by the storm

What Should Be Avoided When Sailing In A Storm?

When sailing in a storm, avoid:

- Getting caught sailing in the storm in the first place : Ideally, a sailor should avoid sailing in the storm in the first place by checking the weather radar and instead wait for the weather to clear before continuing their sailing trip

- Increasing the sail area : Increasing the sail area in a storm should be avoided as it can cause the sailboat to become more unstable and increase the risk of capsizing

- Not wearing a life jacket : Life jackets should be worn at all times when sailing but especially during a storm. Avoid not wearing a life jacket in a storm as there is no protection if someone falls overboard

- Not wearing the appropriate gear to stay dry : Sailors should avoid not wearing the appropriate foul weather gear to stay dry when sailing in a storm

- Not connecting the crew to safety lines/harness : When sailing in a storm, all crew on the boat deck should be

- Not understanding the safety equipment : Sailors should avoid not understanding the safety equipment onboard

How Do You Avoid Sailing In A Storm?

To avoid sailing in a storm, check the weather forecast regularly when going on a sailing trip to know when and where not to sail as the weather gets worse in these areas. If a sailing trip involves passing through a storm, wait in an area where there is no storm until the weather clears up in the storm area before continuing on the voyage.

What Are The Best Sailboats For Sailing In A Storm?

The best sailboats for sailing in a storm are the Nordic 40, Hallberg-Rassy 48, and the Outremer 55.

What Are The Worst Sailboats For Sailing In A Storm?

The worst sailboats for sailing in a storm are sailing dinghies as they offer little protection from the dangers of stormy weather.

What Is The Best Sized Sailboat For Sailing In A Storm?

The best-sized sailboats to sail in a storm are sailboats sized 30ft. and longer.

What Is The Worst Sized Sailboat For Sailing In A Storm?

The worst-sized sailboats to sail in a storm are sailboats sized under 30ft. as it is more difficult to handle rough weather and choppy waves in these boats.

What To Do When Sailing In A Storm

Last Updated by

Daniel Wade

June 15, 2022

Although it’s always advisable to avoid storms as much as possible, they are part of life at sea and sometimes you can’t avoid them. But when a storm comes your way, you should understand how to set up for the storm and how to deal with the worst.

You’ve probably asked yourself; what is it like to sail through a storm? Well, it can be the scariest thing to ever happen in your life. Sailing through a storm will test your strength, endurance, seamanship, and steering skills to the bitter limits. It can wreak serious havoc on your sailboat and any sailor, whether a beginner or experienced should know what to do in a storm when sailing.

Huge storms at sea are a requisite of fear and uncertainty. In most cases, it will sap morale, lead to poor decision making, make the crew members exhausted, and leave everyone in panic mode. Fortunately, it doesn’t need to. In addition to properly preparing the boat, you’ll require a well-thought-out strategy to deal with the sudden and unpredictable changes in weather. More importantly, you should make sure that everybody stays safe, remain calm, and work toward a common goal: overcoming the storm.

In this article, you’ll get to learn about what to do should storm come your way while out there on the water.

Table of contents

Check Your Boat before Sailing

Surviving a storm requires a great level of preparedness and it all begins long before setting out on a sail. As such, your chances of weathering a storm will increase if your boat is properly prepared to endure bad days on the water. A major part of controlling your boat and the crew in a heavy storm is being prepared for the worst. This means that you should have your boat properly rigged to easily access anything in short order.

Whether you can see a storm coming from far away or see it within seconds and on top of your head, the boat should be well prepared to deal with any condition. It’s fundamental to ensure that your lifelines are secure, the lines are strong and unworn, and all the emergency gear is on board and up to date. You should also update yourself on the weather on the days you’re planning to go out though it may be inaccurate.

Tactics for Sailing in Storm

The sailboat is, of course, stronger than people, which means that the main priority is to protect yourself, the crew, and the passengers. In addition to having enough life jackets and harness for everyone in the sailboat, you should take early action to avoid injuries and any form of seasickness as these can affect your safety.

You should also exercise situational awareness by watching your surroundings and monitoring the situation to determine whether the storm is decreasing or worsening. If the situation prolongs, it’s essential to ensure that everybody remains calm, keeps warm and takes time to eat and rest. In other words, this is the right time to show your man-management. Make sure that you maintain high spirits and that everybody works in tandem and are on the same wavelength. This will only work if you calmly work out a plan and communicate the plan to everyone.

Some of the best tactics to use in storm include sailing under storm jib, applying deeply reefed mainsail or applying storm trysail. These tactics will not only give you more control but will also give you more power to steer the boat in the waves. You can also run before the storm and try towing the drogue to slow down the boat.

Stay Away from the Shallows

The first thing that will come to your mind when a storm begins is to drop your sails, start the motor engine, and head off for the land. Well, this can be a very concrete plan as long as you can reach the harbor and dock the boat.

On the contrary, things can become worse if you get stuck in shallow waters. And even if you’re experienced, steering a boat out of the shallows is something else. This is because the winds can rapidly blow you onto the rocks and other obstructions, which can make it a lot more difficult. The engine will most likely die when you need it most.

For this reason, the best option is to stay in open water and use your skills to calmly ride out of the storm.

It’s important to start reefing as soon as you anticipate the storm. The idea here is that you shouldn’t have a lot of sails up in strong winds as this can make the sailboat to capsize. Again, it would be a lot easier to jib or furl the boat if the sails are up. Keep in mind that you should reef the sails when the wind is still manageable. As such, you should pay attention and monitor the winds at all times. Again, do not leave the cockpit if the winds are becoming stronger the boat is being tossed around.

Invest in Storm Sails

There are special sails that can be of great help in heavy winds. Although regular sails can be easily furled and still maintain shape and offer the required efficiency, a storm sail will make it much easier. It will enable you to continue sailing in a storm while reducing the effects of the heavy winds and the big waves.

Sailing in Storms

As we noted earlier, sailing in storms is a huge test of your experience, steering skill, and your overall seamanship. It’s, therefore, important to put your best foot forward and steer the boat effectively without panicking. For instance, you should refrain from sailing across tall breaking waves as they can easily capsize the boat. You should instead sail toward the flat spots while maintaining a high speed to steer out of the huge waves.

You should also target smooth waters if any to prevent the waves from washing across the deck. You can rig a preventer to hold the boom out while being extra careful not to broach the boat’s beam.

Honestly speaking, going through the storm can be a very miserable experience. The most important thing is to ensure that everybody in the body is safe and out of danger. In fact, do not risk your life to save the boat. Of course, your skills, experience, and willpower will be tested to the limits but you should remain calm and come up with a proper strategy that will help you steer the boat to safety. For instance, avoid shallow waters, reef as soon as possible, have storm sails. And make sure that everybody is reading from the same page. More importantly, avoid going out on the water if there’s an impending storm.

Related Articles

I've personally had thousands of questions about sailing and sailboats over the years. As I learn and experience sailing, and the community, I share the answers that work and make sense to me, here on Life of Sailing.

by this author

How to Sail

Emergencies

Most Recent

What Does "Sailing By The Lee" Mean?

October 3, 2023

The Best Sailing Schools And Programs: Reviews & Ratings

September 26, 2023

Important Legal Info

Lifeofsailing.com is a participant in the Amazon Services LLC Associates Program, an affiliate advertising program designed to provide a means for sites to earn advertising fees by advertising and linking to Amazon. This site also participates in other affiliate programs and is compensated for referring traffic and business to these companies.

Similar Posts

How To Choose The Right Sailing Instructor

August 16, 2023

How To Sail From California To Tahiti

July 4, 2023

How To Tow A Skier Behind A Boat

May 24, 2023

Popular Posts

Best Liveaboard Catamaran Sailboats

December 28, 2023

Can a Novice Sail Around the World?

Elizabeth O'Malley

4 Best Electric Outboard Motors

How Long Did It Take The Vikings To Sail To England?

10 Best Sailboat Brands (And Why)

December 20, 2023

7 Best Places To Liveaboard A Sailboat

Get the best sailing content.

Top Rated Posts

Lifeofsailing.com is a participant in the Amazon Services LLC Associates Program, an affiliate advertising program designed to provide a means for sites to earn advertising fees by advertising and linking to Amazon. This site also participates in other affiliate programs and is compensated for referring traffic and business to these companies. (866) 342-SAIL

© 2024 Life of Sailing Email: [email protected] Address: 11816 Inwood Rd #3024 Dallas, TX 75244 Disclaimer Privacy Policy

The Storm Sailing Techniques

Navigating through a storm while sailing can be a daunting task, but with the right techniques and preparation, it can be done safely and confidently. This comprehensive guide provides essential tips and insights to help sailors tackle the challenges of storm sailing and enjoy the adventure.

Sailing is an adventurous and fulfilling lifestyle, but it also comes with its fair share of challenges. One of the most daunting aspects of sailing is dealing with storms. Storms can be unpredictable, and they can test the skills and resilience of even the most experienced sailors. In this article, we will discuss various storm sailing techniques and preparation tips to help you navigate through these challenging situations with confidence and ease.

Table of Contents

Understanding storms and weather patterns, preparation before setting sail, running before the storm, forereaching, lying ahull, storm sailing gear and equipment, safety tips and best practices.

Before we delve into storm sailing techniques, it’s essential to understand the basics of storms and weather patterns. Storms are caused by the interaction of warm and cold air masses, which can lead to the formation of low-pressure systems. These systems can produce strong winds, heavy rain, and rough seas, making sailing in these conditions challenging and potentially dangerous.

To prepare for storm sailing, it’s crucial to familiarize yourself with weather patterns and forecasting tools. By understanding the signs of an approaching storm and monitoring weather forecasts, you can make informed decisions about when to set sail and when to seek shelter.

Proper preparation is key to ensuring a safe and successful storm sailing experience. Here are some essential steps to take before setting sail:

Check the weather forecast: Always check the weather forecast before embarking on a sailing trip. Look for any signs of storms or adverse weather conditions, and plan your route accordingly.

Inspect your boat: Perform a thorough inspection of your boat, checking for any signs of damage or wear that could compromise its performance in a storm. Pay particular attention to the rigging, sails, and hull.

Prepare your crew: Ensure that your crew is well-trained and familiar with storm sailing techniques. Discuss your plans and expectations with them, and make sure everyone knows their roles and responsibilities in case of a storm.

Pack essential gear and supplies: Stock up on essential gear and supplies, such as extra food, water, and clothing, as well as safety equipment like life jackets, flares, and a well-stocked first aid kit.

Create a storm plan: Develop a storm plan that outlines your intended course of action in case of a storm. This plan should include details on how to secure the boat, communicate with your crew, and manage any emergencies that may arise.

Storm Sailing Techniques

There are several storm sailing techniques that can help you navigate through rough seas and strong winds. The best technique for your situation will depend on factors such as the size and type of your boat, the severity of the storm, and your level of experience. Here are some common storm sailing techniques to consider:

Heaving-to is a storm sailing technique that involves slowing the boat down and positioning it at an angle to the wind and waves. This technique can help you maintain control of your boat and reduce the risk of damage from strong winds and rough seas.

To heave-to, follow these steps:

- Tack the boat without releasing the jib sheet.

- Adjust the mainsail so that it’s slightly luffing.

- Turn the rudder in the opposite direction of the wind.

- Adjust the sails and rudder as needed to maintain a steady position.

Heaving-to can be an effective technique for riding out a storm, as it allows you to maintain control of your boat while minimizing the risk of damage. However, it’s essential to monitor your boat’s position and make adjustments as needed to avoid drifting into dangerous areas.

Running before the storm is a technique that involves sailing downwind, allowing the wind and waves to push your boat along. This technique can help you maintain control of your boat and reduce the risk of damage from strong winds and rough seas.

To run before the storm, follow these steps:

- Set your sails for downwind sailing, with the mainsail on one side of the boat and the jib on the other.

- Steer the boat so that it’s running parallel to the waves, with the wind and waves coming from behind.

- Adjust your course as needed to maintain a steady downwind run.

Running before the storm can be an effective technique for managing strong winds and rough seas, but it’s essential to monitor your boat’s position and make adjustments as needed to avoid drifting into dangerous areas.

Forereaching is a storm sailing technique that involves sailing slowly into the wind, allowing the boat to make forward progress while minimizing the risk of damage from strong winds and rough seas.

To forereach, follow these steps:

- Set your sails for upwind sailing, with the mainsail and jib both trimmed in tightly.

- Steer the boat into the wind, maintaining a close-hauled course.

- Adjust your sails and rudder as needed to maintain a slow, steady speed.

Forereaching can be an effective technique for managing strong winds and rough seas, but it’s essential to monitor your boat’s position and make adjustments as needed to avoid drifting into dangerous areas.

Lying ahull is a storm sailing technique that involves allowing the boat to drift freely, with the sails down and the rudder centered. This technique can help you conserve energy and reduce the risk of damage from strong winds and rough seas.

To lie ahull, follow these steps:

- Lower and secure all sails.

- Center the rudder and lock it in place.

- Monitor your boat’s position and make adjustments as needed to avoid drifting into dangerous areas.

Lying ahull can be an effective technique for riding out a storm, but it’s essential to monitor your boat’s position and make adjustments as needed to avoid drifting into dangerous areas.

Having the right gear and equipment on board can make a significant difference in your storm sailing experience. Here are some essential items to consider:

Storm sails: Storm sails are smaller, more robust sails designed for use in strong winds and rough seas. They can help you maintain control of your boat and reduce the risk of damage.

Sea anchor or drogue: A sea anchor or drogue is a device that can be deployed in the water to help slow your boat down and maintain a steady position. This can be particularly useful when using storm sailing techniques like heaving-to or running before the storm.

Heavy-duty foul weather gear: Investing in high-quality foul weather gear, such as waterproof jackets, pants, and boots, can help keep you dry and comfortable during storm sailing.

Harnesses and tethers: Wearing a harness and tether can help keep you secure on deck during storm sailing, reducing the risk of injury or falling overboard.

Waterproof communication devices: Having waterproof communication devices, such as VHF radios or satellite phones, can help you stay in touch with your crew and monitor weather updates during storm sailing.

Storm sailing can be challenging and potentially dangerous, so it’s essential to prioritize safety at all times. Here are some safety tips and best practices to keep in mind:

Monitor the weather: Stay informed about weather conditions and forecasts, and be prepared to adjust your plans as needed.

Communicate with your crew: Keep your crew informed about your plans and expectations, and make sure everyone knows their roles and responsibilities during storm sailing.

Practice storm sailing techniques: Regularly practice storm sailing techniques with your crew, so everyone is familiar with the procedures and can respond quickly and effectively in case of a storm.

Stay on deck: During storm sailing, it’s essential to stay on deck and monitor your boat’s position and performance. This can help you identify and address any issues before they become more significant problems.

Stay tethered: Always wear a harness and tether when on deck during storm sailing, to reduce the risk of injury or falling overboard.

Storm sailing can be a challenging and exhilarating experience, but it’s essential to be well-prepared and prioritize safety at all times. By understanding storms and weather patterns, preparing your boat and crew, and mastering storm sailing techniques, you can navigate through rough seas and strong winds with confidence and ease. Remember to always monitor the weather, communicate with your crew, and practice storm sailing techniques regularly to ensure a safe and successful storm sailing experience.

Sail Far Live Free

Heavy weather tactics: 5 options for sailing through a storm.

- Do you have enough sea room to allow the boat to crab slowly to leeward? The answer will obviously vary depending on your distance shore, the direction of the wind/current, and the longevity of the storm conditions. Remember, heaving-to is a passive tactic, so you’ve got to be o.k. with letting the boat do its thing while you hunker down in the cabin.

- Are your sails and rigging up to the task? As with many storm tactics, your sails and rigging will be subjected to high loads and chafe. Is your boat equipped with storm sails that can handle strong winds and potential flogging? Our boat's sails wouldn't be up to the task of remaining hove-to for hours on end, but I'm confident that I could ride out a short summer squall.

- How well does your particular boat heave-to and will it remain hove-to without putting your beam to the seas? Large swells and breaking waves can be trouble for a boat that doesn’t like to heave-to.

- Do you have sea room to run off? That is, is there land, shallow water or other dangers downwind of your position that make this tactic unadvisable? Furthermore, will running off simply serve to keep you in the path of the storm longer than an alternative tactic?

- Can you maintain steering with the wind and waves on your stern quarters or directly abaft?

- Do you need to deploy a drogue or warps to slow your forward speed in order to maintain control and keep from being overpowered by the waves?

- Are you up for the physically exhausting challenge of manually steering your ship for potentially hours or days on end?

- Sailing a Serious Ocean by John Kretschmer

- The Voyager's Handbook by Beth Leonard

- Heavy Weather Sailing by Peter Bruce

- Storm Tactics Handbook by Lin and Larry Pardey

- Bluewater Handbook by Steve Dashew

- Heavy Weather Sailing Tips - An interview with Allen Breckall on The Sailing Podcast

- Mahina Expeditions - Learn from longtime cruisers and offshore sailors John and Amanda Neal

- YaYa Blues - Join John Kretschmer for a workshop or participate as crew on an expedition

Lots of great advice and references in there, thanks for all the helpful tips! We were caught in an unexpected gale in the Gulf Stream this year with winds sustained out of the north averaging 45 knots for a good 90 minutes. We were running off under bare poles until the winds subsided to the mid 30's, but it worked out well for us.

Thanks Jessica. That's exactly the kind of real world experience I was hoping folks would share in the comments.

We were in a big storm in Stewart Island - New Zealand - getting blown on to a lee shore. We tried to start the motor to help us crab to windward, but in one knock down the motor must have got a big gulp of air instead of diesel. Anyway it meant that the motor cut out. So if you do try and use your motor to assist, make sure you have got a full tank of fuel.

Concerning lying a-hull, it's interesting to read Alan Villiers's account of using this tactic with the Mayflower-II during her crossing in 1957. He wrote "we had no idea what would happen,as no one had attempted this in a ship of this type in over 200 years..." He went on to note that with the sails down, and the rudder lashed to leeward, she pointed up nicely and "lay as a duck on a pond with her head tucked under her wing." (I'm paraphrasing here, since I can't find my copy of Men Ships and the Sea at the moment...) Its' worth noting that ships of that type, with their huge, boxy top-sides had substantially different windage characteristics than our sleek modern designs. From what I've been able to glean, lying a-hull in a square-rigged galleon 300 years ago probably wasn't a terribly different proposition than heaving to under a back-winded jib today.

I should have added that as I understand it at least, it was a maneuver designed to keep the waves on your stern quarter. Same principles, just facing a different direction? I'm gonna have to find my copy of that darn book now, as I'm confusing myself and sounding like an idiot.

Thanks for your wonderful and so helpful tips. We also would like to invite you to our Sailing Community - Clubtray Sailing Clubtray Sailing where members could be more helpful by your great advices and references. Hope to read more kind of real world experiences from you soon.

Post a Comment

Popular posts from this blog, top 10 favorite affordable bluewater sailboats, go small and go now 5 pocket cruisers to take you anywhere.

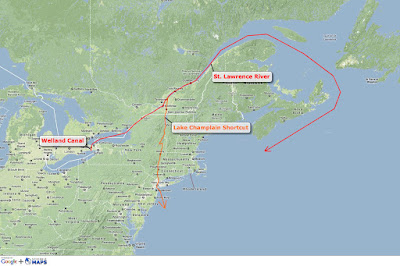

Escape to the Sea: How to get from the Great Lakes to the Caribbean

Dealing with bad weather on a catamaran

Home The Blue Blog Dealing with bad weather on a catamaran

The bad sea is the greatest fear when you are at sea, even if the chances of being caught in a storm are very remote. Every good sailor knows how and when to face the sea, modern weather systems guarantee precise and continuous bulletins. However, facing bad weather on a catamaran is certainly easier and safer than many other boats. Avoiding the rough sea is easy, but if fate wants you to find yourself in the middle, these boats offer exceptional performance. Modern catamarans are very durable, even in rough seas, and they have excellent buoyancy. The risk of a reversal is certainly poor, it can withstand sustained waves and wind. There are areas where time can change abruptly, but not to the point of surprising a boat unless you sail on ocean routes. The particular structure of the catamarans allows good navigability and maneuvering management, in addition to the fact that it can also reach a good cruising speed. Obviously the skipper needs to know his business, because if the wind was badly caught it could lift the catamaran with compromising consequences.

What to do to face bad weather on a catamaran

The psychological side is fundamental, never panic and evaluate all possible options. The first thing to do is update on the weather conditions of the route taken, taking into account the direction of the storm, the distance of the nearest port and possible escape routes. All with the necessary coldness and lucidity in these cases, panic does not help and only complicates things. When the situation is clear, the most correct strategy must be adopted to avoid the risk of finding yourself in the middle of the rough sea. Organizing the crew and passengers in a precautionary way, prevention can always prevent the worst. Every member of the crew must be ready to offer his contribution if necessary. Always wear life jackets and belts, and lock all moving objects that could be thrown into the cabin by storing them in the lockers. If the tender is in the water, hoist it on board and tie it securely to prevent it from drifting or becoming a problem on the deck. Close all the hatches and portholes to prevent the water from entering the cabin, the rain could be sudden and copious.

Precautions not to be surprised by the rough sea

Obviously all the actions and precautions must be carried out to avoid the worst and not to be caught unprepared, if you approach even the storm, the effects will be largely mitigated. The catamaran can face the rough sea but it is necessary to know its qualities but also its limits. If everything is done as it should, the chances of even discomfort will be minimal.

Most of the time the weather warnings arrive even days in advance, so the surprise effect is certainly to be excluded. In any case, every possibility must be taken into serious consideration, being ready for any bad weather, rain or rough sea is necessary.

Ask for a customized quotation

We are here to advise you

BE INSPIRED

Among our many destinations, choose the one you prefer for your sailing cruise and leave for the holiday of your dreams

Wishlist ( 0 )

I declare i have received the information and i give consent to the processing of my data:.

I have read and accepted the privacy terms

Ask for information

Specifications.

Heavy Weather Tactics

Scores of books have been written about heavy weather sailing, but few of them address the particulars of multihulls and their individual considerations. Monohulls have more commonalities as a group, therefore there are more general guidelines. Storm tactics for multihulls will depend more on the capabilities of crew and vessel than any other factors.

Barreling along at 18 knots in strong winds can be thrilling and is a highlight of multihull sailing. Making no seamanship errors will be as important as the simplest rules of keeping all lines neatly organized and kink free. Often tangled lines have gotten sailors into more trouble than anything else. Keeping a neat cockpit and thinking ahead are the cheapest insurances against mishaps.

In heavy weather the boat should be set up with appropriate safety lines and attaching yourself to them must be mandatory, even if one only ventures briefly into the cockpit. All crew should wear full gear and always have their life jackets at the ready. Each member should have a strobe, knife and whistle permanently attached and there always should be a big knife with a serrated edge mounted in the cockpit to quickly cut a jammed line, if necessary. Basic safety drills, location of life saving equipment, rafts and throw-able MOB devices must be known to each crewmember. Everyone on board must understand the crucial function of EPIRBs, VHFs, firefighting equipment, as well as engine operation and bilge-pump system. It is all really common sense.

If in the highly unlikely event that you capsize, stay with the boat at all costs. Rig one life raft or dinghy to the underside of the bridge deck, fly a kite and wait for help. Never, ever separate from the mother ship as your chances of being spotted will be close to zero in a raft. Staying warm, hydrated, and clear headed will be as important as keeping crew morale up. Salvage as much food and water as you can and secure them, as waves in the interior will wash them out any opening. It has been suggested to await help in the upturned vessel, but unless it is a perfect calm, it will be impossible. Wave surges in the cabins will be violent and there will be leaking battery acid, foul smells and floating objects that will force you onto the upturned platform of the bridge deck.

Storm strategies will depend on the sea state. The shorter and higher the wave faces, the more critical correct seamanship will be. It is my opinion that the use of sea anchors should be carefully weighed and avoided if one can actively deal with the conditions. In theory, they work well if conditions do not change. The crew can rest and the multihull will make nominal drift downwind, provided there is minimal searoom. But the sea is a chaotic environment and waves do not always remain in one and the same pattern, direction, and period. The forces and loads on the boat when tied to a parachute type device can be huge.

True and Apparent Wave Height

Imagine your boat hanging off a sea anchor and suddenly a wave from a different direction slams into the boat from the side. As the boat is not moving, actually drifting slightly backwards, it will not have any possibility to handle this odd rogue wave. The catamaran might be overwhelmed and rotate around its longitudinal axis and flip. Most cruising catamarans that have capsized were constricted by sea anchors. In one well-documented incident, the parachute's lines caught under the rudders and turned the boat.

A sea anchor might lull you into a false sense of security and your vigilance will be reduced. Being caught with your guard down is the most dangerous situation, and I feel it is better to actively deal with storm conditions, rather than letting the boat drift off a sea anchor. Besides, retrieval and deployment are risky, and if not done properly the first time, they can subject crew and boat to more risks.

This is not to say that a parachute anchor does not work. On the contrary, many multihulls have ridden out hurricanes with these devices. Personally, I would want to position the boat to sail with the seas if there is sea room. The vessel's speed should be adjusted to the wave period and therefore would reduce the relative impact of waves. If one's cat sails too fast, even without sails up, a drogue or warps could be dragged behind the boat. Streaming warps off a stern bridle will also be helpful if the boat has lost steerage. It will keep the bows pointing downwind. Ideally, seas should be taken off the rear quarter in order to present the longest diagonal axis to them. This will be the most stable attitude, and a good multihull will be able to handle the most severe conditions. A well-working autopilot, an alert crew, and a strong boat will get you through anything. Concentration will deteriorate as the conditions worsen and any mistake will be very difficult to rectify. Your margin for error will be minimal and advance thinking and anticipation will be key. Approaching a safe harbor during heavy weather can be nerve-wracking and should be carefully weighed with the risk of running aground and encountering much rougher than usual inlets. Often standing off will take discipline but be safer.

Again it should be mentioned that everyone manages differently with storm conditions and there is not necessarily only one right or wrong way to do it. Making the vessel's speed work for you and being able to

Wave heights make great subjects for sea tales, but the altitude of seas are often overestimated. Especially on smaller vessels, when the horizon is hidden, one feels that the seas are steeper than they actually are. The apparent gravitational pull makes one think that the boat is sailing parallel on the horizontal plane. Usually however, the boat is already ascending the next wave, leading to estimation errors as high as 50% in judging wave heights.

Safely slowing the multihull is accomplished by streaming warps or trailing a special drogue. A large bridle is either fastened to the windward hull or to the sterns.

Streaming Warps or a Drogue to Slow Down

Streaming Warps or a Drogue to Slow Down outrun a system will reduce your exposure time. Drifting slowly downwind tied to a sea anchor will expose you to bad weather longer. The advantage of a fast catamaran should be used to get you out of trouble, or even better, by using today's advanced meteorological forecasts, you might be able to avoid it entirely. Yet, once you are in storm conditions, slowing down the boat to retain full control will be challenging.

If there is no sea room, or one is forced to claw upwind, reducing speed to minimize wave impact is imperative to the comfort of the crew and safety of the boat. Finding the right groove between stalling and too much speed is important. You do not want to be caught by a wave slamming into you, bringing you to a halt. This could end up in a lack of steerage and, in the worst case, you could be flipped backwards. Always keep on sailing at a manageable speed and if your boat has daggerboards, both boards should be down one third only. Head closer to the wind towards the top of the wave, and fall off as the boat sails down the slope. This will aid in keeping the sails drawing and boat speed in check. Structural shocks upwind in very strong winds can be very tough, so find the right speed. Reducing your main to 3 or even 4 reefs and furling your headsail for balance will drive you to weather. We all know that this will not be comfortable, but if there is no choice other than to windward, one will manage until conditions have abated. Flatten sails as much as you can to depower the boat. If you need to tack, plan ahead, do it decisively, and with plenty of momentum. You do not want to be caught in irons while drifting backwards. Loads on the rudders with the boat going in reverse can damage the steering, leaving you crippled.

Running off at a controllable speed is the safest way to handle a storm. If you are deep reaching or sailing downwind with the storm, retract both boards if your boat has daggerboards. In the event that the catamaran is skittish and hard to steer, lower one foot of daggerboard on both sides. Long, well balanced, high-aspect-ratio hulls, especially ones equipped with skegs far aft, will track well, even without boards. A tiny amount of jib sheeted hard amidships might be all that is needed to point the boat downwind. Reduce the boat to a speed where you are just a fraction slower than the waves.

Keep in mind that the term "slow" is relative as this could still mean that you are traveling at well over 15 knots!

Sailing with the beam to the storm and seas should be avoided at any cost. If, because of say navigational issues, one has no choice, both daggerboards must be lifted to assure sideways slippage.

Heaving-to is a tactic which lets the boat sail controlled, almost stationary, and should be used only if one has no more alternatives.

This could be caused by crew exhaustion or mechanical issues with the boat. When heaving-to, the helm is locked to windward, a tiny scrap of jib sheeted to weather, and/or a heavily reefed mainsail can be set. The traveler should be let off to leeward and, theoretically, the multihull will steadily work herself to windward. At 40 degrees, she will either be stationary or slightly fore-reach. This does not work on all multihulls and different mainsail and jib combinations should be tested. Also letting the main or jib luff slightly will take speed off the boat, if

far right Boarding via the transom platform, any guest will easily find his/her way to the spacious cockpit by walking down wide, teak-covered steps. Notice the lack of any sail controls or helm station - they are all located out of the way, on the flybridge above.

so desired. Catamarans with daggerboards should only have very little windward board down to avoid tripping.