Adding a staysail

A properly rigged staysail is a great passagemaking tool.

Sail selection is key for offshore sailing. You need a combination that provides speed without overburdening the boat and enough flexibility that you don’t have to make frequent sail changes.

Everyone knows what to do when the wind pipes up: take a reef in the main and roll in some headsail. If you are on an afternoon sail, a reefed headsail is OK, but it’s not perfect. The effect of rolling in the sail raises the center of effort, inducing more heel, and the sail shape and the sail suffer. Offshore, these attributes will slow you down and make for a miserable passage. A better solution is to use a staysail, the center of effort will be low and the shape perfect.

With the exception of bluewater battlewagons, you don’t see staysails on most boats these days, and for good reason. Placing a stay right in the middle of the foretriangle makes tacking the genoa difficult, and it’s a few thousand dollars of gear and weight that seldom get used on a coastal afternoon. But for offshore sailing, the extra hassle and cost are well worth it.

On a typical bluewater boat, a single reef and a staysail are perfect for going to windward in more than 25 knots. A deeper reef will allow you to make way in higher winds. A tough boat can forereach through about anything with a deep mainsail reef and a robust staysail setup.

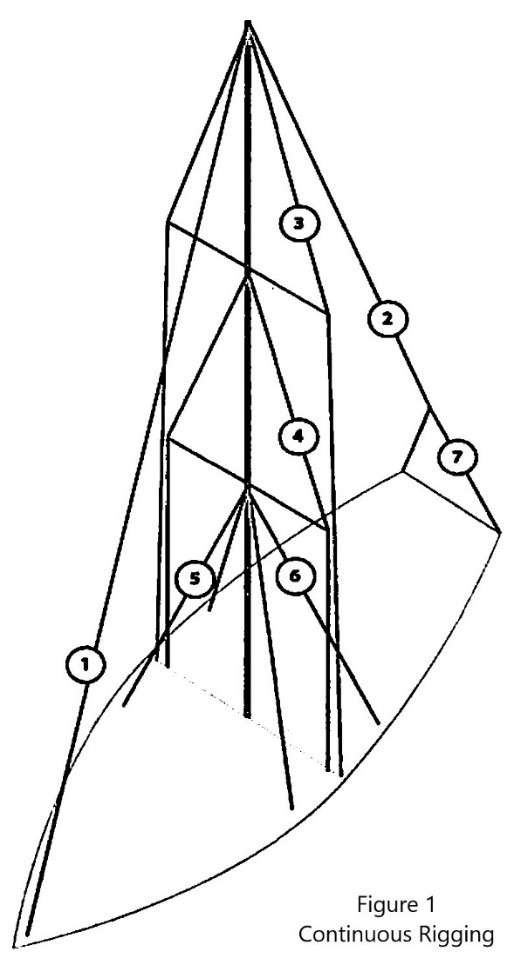

There are three items that need attention when adding a staysail: the standing rigging, the running rigging and the sail itself.

In order to install a stayed staysail, you are essentially adding a second forestay about a third closer to the mast. The stay attaches to the deck about a third of the way back and to the mast around the upper spreader. It’s important, although not critical, that the staysail stay is parallel to the forestay. You can play with the angle a little, but it will look the best parallel.

While the stay seems simple, there are big forces at play here. When loaded up, the stay will pull upward on the deck and forward on the mast, and forces need to be opposed. A deck seems pretty strong, but it will deflect and fail if you attach a chainplate right in the middle of your foredeck. The most common way to reinforce the deck is by attaching the chainplate into a bulkhead, perhaps at the aft end of the chain locker. Another common solution is to use a tie rod attached to the hull, allowing the rod to transfer the load to the much stronger hull.

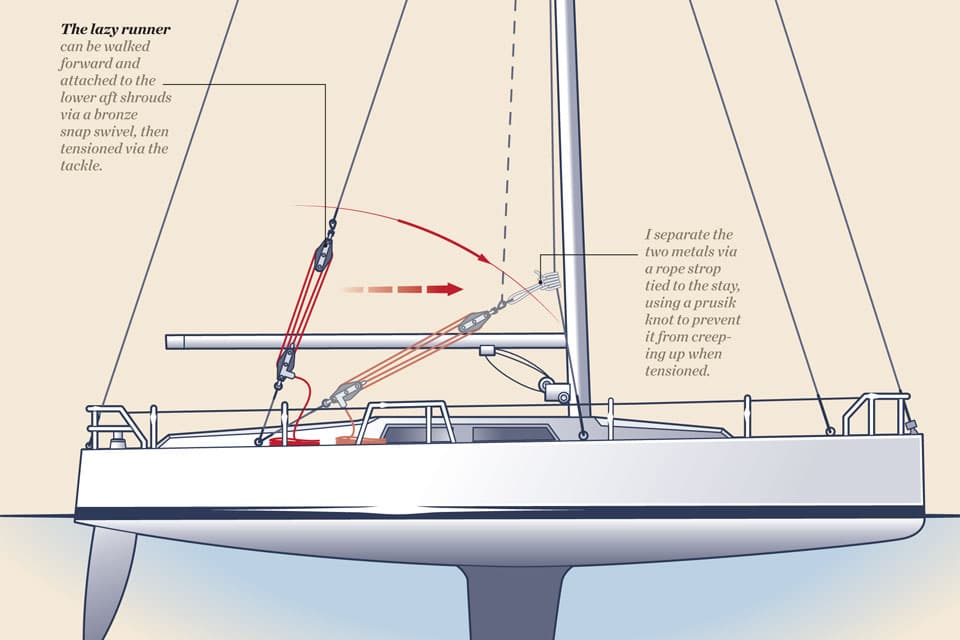

The next force to deal with is the one pulling the mast forward. Every stay on your boat has an equal and opposite partner balancing the loads. With the staysail pulling forward and to leeward, we need a stay that will pull backward and to windward, at roughly the same angle. The same angle part is important, people have tried to use aft led intermediate stays, but the angle on those is typically way too steep to be effective. You will need running backstays, and yes, they will get in the way of the main, but it won’t be a big deal.

The first decision to make is how you want the stay set up. Do you want a fixed wire stay, a furler or maybe a removable cordage stay? A fixed wire stay allows you to hank a staysail on directly and go to sea. It’s a bulletproof solution, but there are negatives. You’ll need to go on the foredeck and hank on a sail to use it. A deck bag can help, but it’s still a hassle. The less obvious problem is that a bare wire stay is hard to tack the genoa around because the sail will almost always hang up on the wire. A furler solves both these issues: you can deploy from the cockpit and the furled sail presents a more slippery surface to tack around.

If you want a hanked-on sail, a more modern solution is a cordage stay. These stays are typically made of heat-treated Dyneema like Dynice Dux or New England STS, and winch tensioned through a block mounted to a padeye on the deck (reinforced as previously discussed) and to a rope clutch winch. The main benefit here is that the stay is easily removable and stowed like a halyard. A wire stay will clank around, but the lightweight Dyneema will stow nicely. If you choose a cordage stay, you will need to use soft hanks on the sail as standard bronze hanks will quickly chafe the cordage.

With the stay figured out, running backstays need to be addressed. The runners will go from the mast to as far aft and outboard as you can run them, to get as much advantage as possible to oppose the staysail. On any boat longer than 40 feet, you’ll need to lead the runner tails to winches, as the loads are just too high for a tackle alone. Invariably wire runners will chafe on the main and clank around when tacking. Heat-treated Dyneema comes to the rescue again, the material is very strong and won’t chafe the main, but handles loads like stainless steel wire. The lightweight property of the cordage makes them very easy to stow as well.

Use tangs to attach the runners to the mast, where a slot to accept the tang has been created and reinforced. These fittings will securely connect the stay to the mast and provide a large radius bearing surface for the cordage to ride on, they attach easily with a through-bolt or T-Ball adapter.

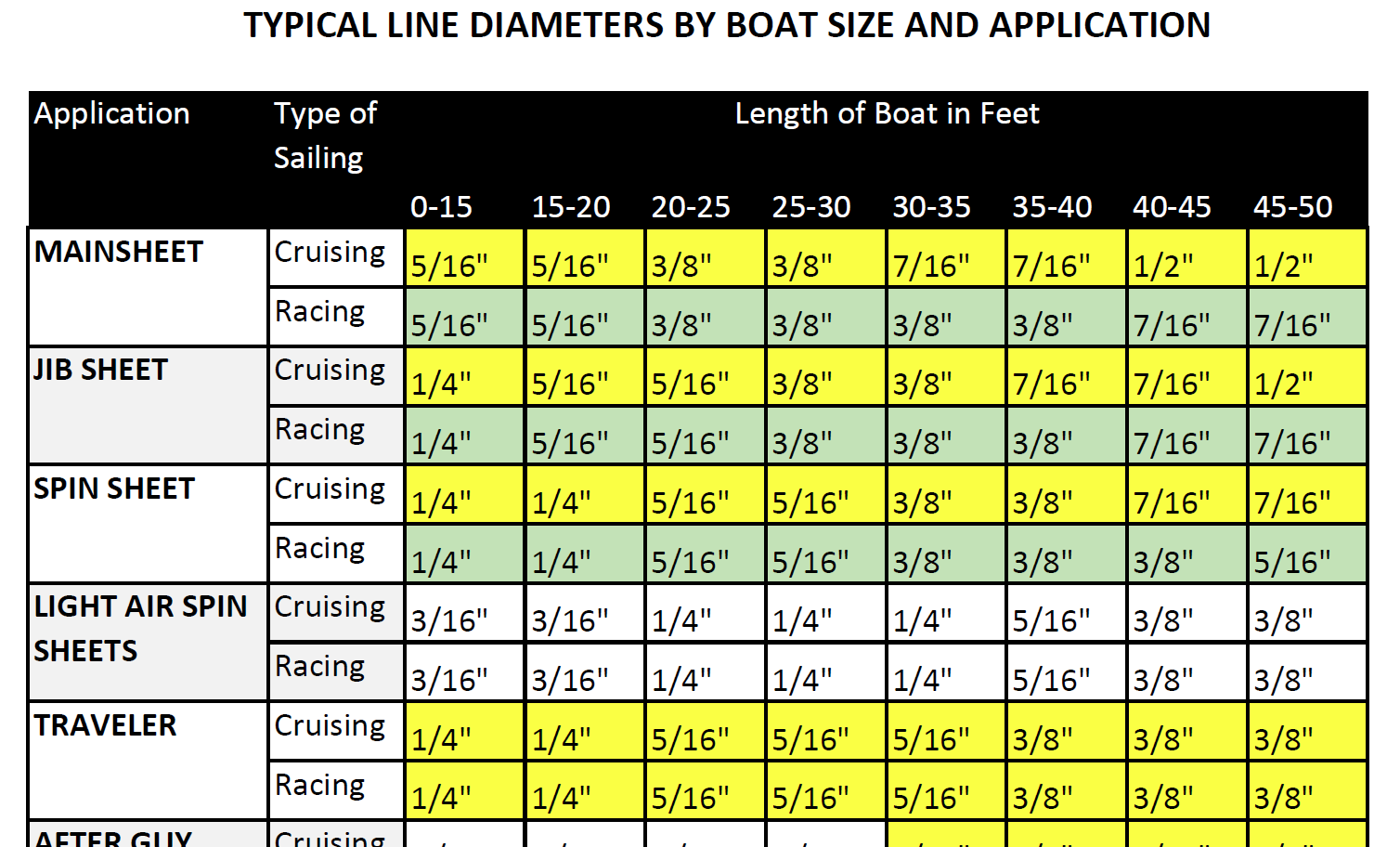

Staysail running rigging is not a complicated matter, but you want to get it right. Sheets can be tricky to lead and you may have to install a new fixed block or lead to a car on a very short track. It’s important that the lead is good, avoiding chafing on the shrouds, cockpit coaming, dodger and anything else that gets in the way of a fair lead to the winch. Since a staysail is a great sail in a blow, expect this to be a high-load setup.

Work with a sailmaker to build a nearly bulletproof sail, built with heavy cloth and heavily stitched appropriate for the high winds you’ll be using it in. Also make sure to discuss the foot height with your sailmaker, as you want to keep the center of effort of the sail low to reduce heeling, but high enough off the deck to prevent it from catching green water that breaks over the deck.

Engineering a staysail for your boat can be a lot of work, but it adds a lot of flexibility and capability to your sailplan. Do the work carefully and it will pay dividends over many stormy miles.

Also in Technique

- Winch servicing

- Repairing delaminated core

- Splicing Dyneema

- DIY custom bug screens

- Anchoring and mooring a catamaran

- Co-owning a boat

- Installing a steering wheel

- Helming skills

- Captain your own charter

- Asymmetric spinnaker skills

Also from Bob Pingel

- How do I stop my mast from leaking?

- How should I rig a preventer?

- Tachometer troubles and lazy jack mounting questions

- Do I need to add running backstays?

- What’s with the sour smell on my boat?

- Why is there water in the bilge when I run the engine?

- How do I make sure my VHF works properly?

- Installing a boiler for cold-weather sailing

- How do I fix my hot water system?

- Yachting World

- Digital Edition

Staysails: 5 tips on using them to turbocharge your boat speed

- February 10, 2020

Andy Rice gets top tips on how to use a staysail to turbocharge your boat from Volvo Ocean Race winning skipper Mike Sanderson

Staysails really come into their own during long periods of strong winds, such as the Fastnet Race. Photo: Carlo Borlenghi / Rolex

As Mike Sanderson points out, staysails are hardly a new idea. The old clipper ships used to use multiple staysails. However, the past five years have seen staysails become a ‘must have’ item on high-performance raceboats, not least in the Volvo Ocean Race , where footage of triple-headed VO65s blasting along became some of the defining images of the 2017-18 edition.

As sailors are increasingly looking to gain smaller and smaller advantages in competition, staysail technology is trickling its way further down the sport. Mike looks at which kind of boats are best suited to deploying staysails, and how best to use them on the racecourse.

Genoa staysails tend only to appear on the highest performance raceboats that generate significant apparent wind. So here, Mike focuses his tips on spinnaker staysails, which are more applicable to a wider range of boats.

1. What ’ s your angle?

It’s surprising how little you need to ease sheets from close-hauled to start feeling the benefit of adding a genoa staysail. Provided the wind is more than 7 knots, even just bearing away 10° or 12° from fully upwind means you can start to feel the benefits of a genoa staysail.

Spinnaker staysails tend to come into play once you’re sailing at an apparent wind angle between 38-90°. Provided your boat experiences that kind of apparent wind angle (AWA) with a spinnaker or gennaker up when VMG running, chances are that a staysail will improve your performance.

A staysail will continue to work until quite a deep angle, but not when you’re getting close to dead downwind. Once you go beyond 150° to 155° true wind angle, you’re often better off furling it away.

Article continues below…

How to balance speed and comfort when sailing – top tips from Pip Hare

Most of us now rely on some form of routeing software when sailing offshore. These packages calculate the fastest theoretical…

Helming downwind: Pip Hare’s top tips on how to maximise your speed

For me, helming downwind, particularly in big breeze, is one of the absolute joys in this world. It is a…

2. No penalty power

The beauty of the staysail is that rating rules like IRC and ORC don’t penalise you for using it. It’s measured as a jib, so you’re getting added power for no penalty.

On a Maxi 72, a spinnaker staysail will give another 100m 2 of sail area, which powers up the boat more, bringing the apparent wind forward. It’s a very efficient way of increasing the flow across the sail plan, enabling you to sail faster and deeper downwind.

3. Use the jib

Once it gets windy on a high-performance boat, you might want to just leave the jib up and have that working as your staysail. If you’re racing on a short windward/leeward course, the risk of sending the bowman up on a white water foredeck might not be worth it.

You’ll notice that small sportsboats like J/70s and SB20s tend to keep their jibs flying downwind in most conditions, because it provides added power and improves the flow over the back of the mainsail, just like a dedicated staysail would do.

If you’ve got 100 miles of strong wind straight line sailing ahead of you in a Fastnet Race , for example, then the staysail is a no-brainer. In rough conditions, if in doubt, stick to the jib, and save yourself the potential jeopardy of stuffing up the staysail.

On slower, lower performance boats, you will want to keep the staysail flying for longer, most of the way up the wind range until you’re thinking about using the J4 jib. In many cases the staysail is an easier sail than the jib to handle through gybes as it can be furled.

4. Spec your staysail

When ordering your staysail, we talk about percentage of STL, or the bowsprit length. The longer the bowsprit, the closer to the headstay you can mount the attachment for your staysail.

That’s the case on a Maxi 72, for example, but if you’re operating with a short prod then you will need to mount the attachment further aft along the foredeck. Otherwise it will interfere with the flying of the gennaker and can also be a real hassle for the bowman to get the jib down and furl the staysail – dealing with the bulk of the jib and the risk of the furler line jamming in the jib and so on. This means you’ve got a trade-off to consider between performance versus boathandling.

5. Trim for speed

Trim the staysail like you would trim the jib. If in doubt about how much to sheet on, it’s better to have the luff slightly luffing rather than oversheeting it, but really just keep focussed on the telltales, especially around the middle of the sail.

If you have a fixed, non-adjustable sheeting point then you may want to have a series of strops for the tack of the sail so you can adjust the lead position by raising or lowering the whole sail off the deck at the tack, which achieves the same effect as adjusting the lead.

About the expert

Mike Sanderson is one of the most respected professional sailors on the circuit, having skippered ABN Amro to victory in the 2005/06 Volvo Ocean Race and sailed with Oracle in the America’s Cup . These days Mike is chief executive of Doyle Sails and races on board the Maxi 72 Bellamente .

First published in the February 2020 edition of Yachting World.

Cruising Sail Trim Guide: Staysail

Cruising with your staysail can add horsepower and ease, giving you options in a variety of conditions. Learn how to make the most of your cruising experience with Quantum expert Dave Flynn’s staysail trim guide.

The staysail plays three roles:

- It augments sail power.

- It helps break down total sail area into smaller working components for ease of handling.

- The smaller sail units allow for different combinations, giving sailors a variety of options for different conditions.

To make the most of your staysail, learning how to trim it is key. First though, it helps to know the right conditions for using a staysail.

As part of the overall sail power of your boat, the staysail is most useful in the middle range of reaching angles, from a close reach to the point where the wind is slightly aft of the beam (50-130 degrees apparent wind angle). As the boat sails at broader angles, the blanket of the mainsail, as it is eased out, limits the effectiveness of the staysail. Eventually, the staysail will be hidden behind the mainsail. At closer angles, when sailing to windward, the staysail can help augment horsepower.

As the headsail, staysail, and mainsail are trimmed in, the gap (slot) between them narrows, and they begin to affect each other. In lighter conditions (under 10-12 knots apparent), the staysail may inhibit, not help, upwind performance. In the middle ranges, the staysail can be more helpful, depending on factors like sail shape and sheeting angle. In windy conditions, as the mainsail has to be eased, lowering the staysail will allow the mainsail to breathe and reduce back-winding, helping to keep the boat on its feet. In short, the optimum conditions for the staysail (when adding horsepower), are at apparent wind angles of 50-130 with a minimum apparent wind velocity of 10-12 knots.

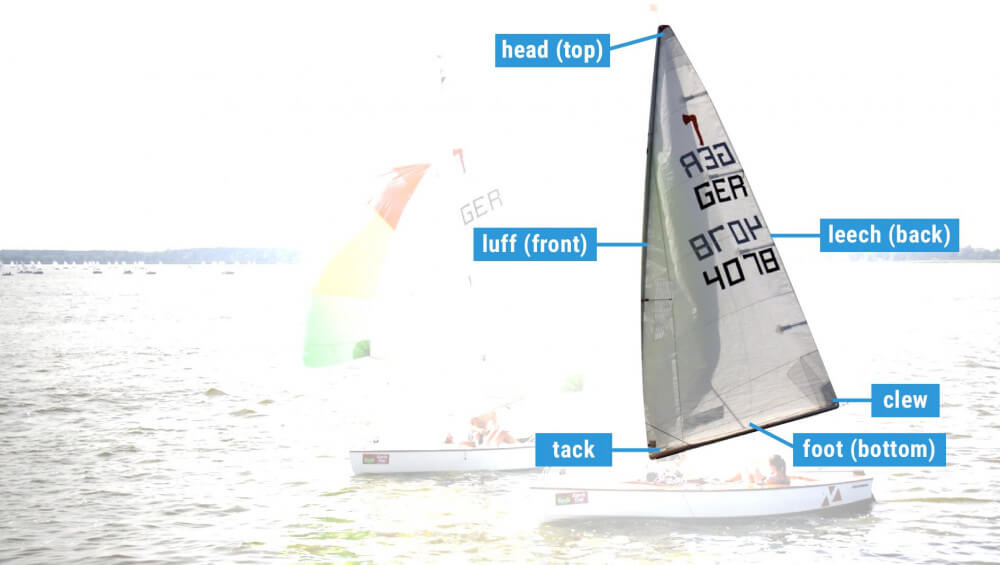

Trim of the staysail is really no different than any other headsail. When reaching, keep in mind the first rule of sail trim: when in doubt, let it out.

Most sailors tend to over trim. Make sure the sail is eased to the point of luffing, then trim to barely remove luff. If your boat is not equipped with a Hoyt club boom, the sheet lead should be moved to the outboard rail as the sail is eased out. The lead position should follow the clew, moving slightly forward and outboard.

If your boat is equipped with a Hoyt boom, the staysail’s tendency to twist (leech opening up and causing the top of the sail to luff before the bottom) can be controlled by the boom. The Hoyt boom makes the staysail more useful at broader wind angles since sail shape is maintained and the sail is extended straight away from the boat as it is eased. There is less interference with the mainsail as a result.

Upwind, trim in tight, but be careful. When looking up the sails from the aft quarter, the slot between the three sails should be roughly parallel. The genoa should be trimmed in almost to the spreader – trim the staysail to match this profile.

If your boat has a conventional jib track, make sure the lead isn’t too far forward. If it is, the foot of the sail will be round and full. This will just create back winding in the mainsail. Drop the lead aft until the foot of the staysail is flat. With a Hoyt boom, make sure the outhaul is pulled tight to achieve flat foot sections.

When it gets windy, the staysail is the perfect sail. Used in combination with a partially-furled genoa or working jib and a reefed mainsail, the staysail provides plenty of power. Various combinations of reefs and headsail size allow the boat to be balanced in every condition.

Don't miss Quantum's trim guides for your headsail , mainsail , and asymmetrical sail .

Dave Flynn Quantum Sails – Cruising Guru 410-268-1161 [email protected]

The Discussion

Us, too. We pour that passion into each of our newsletters to help you enjoy sailing even more.

- New Sailboats

- Sailboats 21-30ft

- Sailboats 31-35ft

- Sailboats 36-40ft

- Sailboats Over 40ft

- Sailboats Under 21feet

- used_sailboats

- Apps and Computer Programs

- Communications

- Fishfinders

- Handheld Electronics

- Plotters MFDS Rradar

- Wind, Speed & Depth Instruments

- Anchoring Mooring

- Running Rigging

- Sails Canvas

- Standing Rigging

- Diesel Engines

- Off Grid Energy

- Cleaning Waxing

- DIY Projects

- Repair, Tools & Materials

- Spare Parts

- Tools & Gadgets

- Cabin Comfort

- Ventilation

- Footwear Apparel

- Foul Weather Gear

- Mailport & PS Advisor

- Inside Practical Sailor Blog

- Activate My Web Access

- Reset Password

- Pay My Bill

- Customer Service

- Free Newsletter

- Give a Gift

How to Sell Your Boat

Cal 2-46: A Venerable Lapworth Design Brought Up to Date

Rhumb Lines: Show Highlights from Annapolis

Open Transom Pros and Cons

Leaping Into Lithium

The Importance of Sea State in Weather Planning

Do-it-yourself Electrical System Survey and Inspection

Install a Standalone Sounder Without Drilling

When Should We Retire Dyneema Stays and Running Rigging?

Rethinking MOB Prevention

Top-notch Wind Indicators

The Everlasting Multihull Trampoline

How Dangerous is Your Shore Power?

DIY survey of boat solar and wind turbine systems

What’s Involved in Setting Up a Lithium Battery System?

The Scraper-only Approach to Bottom Paint Removal

Can You Recoat Dyneema?

Gonytia Hot Knife Proves its Mettle

Where Winches Dare to Go

The Day Sailor’s First-Aid Kit

Choosing and Securing Seat Cushions

Cockpit Drains on Race Boats

Rhumb Lines: Livin’ the Wharf Rat Life

Re-sealing the Seams on Waterproof Fabrics

Safer Sailing: Add Leg Loops to Your Harness

Waxing and Polishing Your Boat

Reducing Engine Room Noise

Tricks and Tips to Forming Do-it-yourself Rigging Terminals

Marine Toilet Maintenance Tips

Learning to Live with Plastic Boat Bits

- Inside Practical Sailor

The DIY Solent Stay or Inner Forestay

Among the many rigging improvements I’m pondering for my Yankee 30 Opal the year ahead is installing a second forestay to allow more flexibility in my sail plan.

A few years ago we dove into this topic in a two-part series on headsails. Two articles discussed the advantages of retrofitting a sloop with an inner forestay so that a smaller headsail could be set in higher winds. In the first part, technical Editor Ralph Naranjo discussed the Solent stay. In the the second part if the series , sailmaker Butch Ulmer wrote about the advantages of an inner forestay or staysail stay.

A Solent stay is a stay that sets between the mast and the forestay. It connects to the mast at a point that is only slightly below the existing backstay, and meets on the deck only slightly abaft of the existing forestay. Under such an arrangement, the mast requires no additional support. The existing backstay provides adequate tension to counteract the loads of any sail that is set from the new stay. Because it requires no additional backstay support, a Solent stay is a slightly less expensive option than the more common staysail stay, and it offers many of the same advantages.

An staysail stay also sets between the mast and the forestay. As the name implies, a staysail stay is where you would set a staysail, although it is also commonly used for setting a storm jib. In this modification, the forestay joins to the mast much closer to the deck than the Solent stay, so that some support aft is needed, usually in the form of running backstays-backstays that can be tensioned when needed, and slacked out of the way when they are not required. The staysail stay meets at the deck further aft than the Solent stay, thus bringing the center of effort further aft, which is usually desirable in heavy weather.

Why add an additional stay? As we saw in part one of our report, a Solent sail or staysail stay resolves the difficulty in managing a boat in winds at the upper range of a roller-furling jib’s designed parameters (usually above around 30 knots). The failings of a roller-reefed headsail become especially apparent when trying to work to windward. Even the best-cut furling jib will not furl down to the same efficient shape of a sail designed to perform in higher winds. There is also the risk of the furling gear itself failing, or the jib unfurling to its full dimensions.

It is important to keep in mind that most coastal sailors don’t need to bother with either of these stays. If you a prudent near-shore sailor, a well-designed and constructed furling jib will usually serve just fine. Butch Ulmer’s report discussed several methods sailmakers use to improve the performance of the roller-furling headsail when reefed down. A padded foam luff, conservative sizing (so reducing the size of the furled sail), stiffer sail material, and more sophisticated construction can all help make the furled sail more efficient. However, several of the sailmakers we spoke with suggested that a second forestay would be a welcome addition aboard a boat that has aspirations for a long offshore cruise.

The most common question we were asked in the wake of our recent two-part series on headsails was, “How do I install an inner forestay or Solent stay?” Because either of these stays might one day be depended upon in the direst of circumstances, and because every boat presents different challenges for this project, it’s important to do your research and investigate other boats that have carried out this retrofit. Once you have a general idea of what features you like, consult a rigger for the initial design.

The rigger can also help you source the parts you need, and hopefully point out other details you might overlook, such as where to install the sheet leads, how to prevent corrosion of the new hardware, and what deck reinforcements might be required. If you are having a sail made for the new stay, then getting the sailmaker involved in the design will also help.

Once you have your measurements and hardware, you can carry out the installation, depending upon your ability. In some cases, you may need some fiberglassing skills, since the padeye/chainplate for the new stay must be adequately reinforced. Usually, fiberglass work can be avoided by transferring the load to the hull or a stout bulkhead, but as Brion Toss demonstrated in his recent article on the hidden causes of rig failure , this requires a general understanding of common installation errors and potential trouble spots.

For those who are considering an upgrade here are some other resources to consult as you begin your search.

- Don Casey’s This Old Boat Casey’s comprehensive book on upgrading an old sailboat dedicates several pages to adding an inner forestay. This comprehensive book is a must-have for anyone planning to turn a run-down sailboat into the pride of the marina. You can probably find a used copy on Amazon, but if you buy new from our bookstore , it helps support more Practical Sailor tests and special reports.

- PS Advisor Adding a Staysail Back in 1999, when former editor Dan Spurr was refitting his sloop Viva , he pitched this same question to naval architect Eric Sponberg, who offered some sage advice. This article also references three books that will be of help to anyone considering a retrofit, among the Understanding Rigs and Rigging by Richard Henderson.

- Whence Thou Comest, Highfield? We don’t know what was in the (former) editors water bottle when he came up with the headline for this test of quick releases for stays and shrouds back in 1999. After evaluating several devices, the test team concluded that ABI’s Highfield lever to be the best of the bunch. The company has since gone out of business, but the as the Rigging Company describes, three other worthy substitutes are now available. We routinely turn to the Rigging Company for advice on hardware and installations and its website has a section dedicated to installing an inner forestay that covers many of the hardware details, including devices for storing the inner forestay when not in use.

- Spar specialists Selden has a number of informative articles on rigging installation and maintenance. It offers step-by-step advice on installing an inner forestay fitting (nose tang) on the mast. For those who are dealing with a classic boat, fabricating their own chainplates or tangs, or simply enjoy digging into archaic, yet still valuable advice. Skene’s Elements of Yacht Design offers tips on calculating loads and fabricating hardware. It is still relevant enough to pick up from a used book store. Rig-Rite also offers a selection of staysail tangs.

- Rigger and sailmaker websites In addition to its discussion of stay releases the Rigging Company has additional information on adding a Solent stay. Brion Toss’s Spartalk discussion board (log-in required) has several threads dealing with inner forestays, Solent stays, and related hardware. Among them is Toss’s rant against the ABI forestay release . He prefers the babystay releases from Wichard (see page 9 of the catalog), available in wheel, ratchet, or lever designs, depending on the size of the boat. And sailmaker Joe Cooper describes a lightweight Solent stay retrofit using fiber instead of wire for the stay. (Because of unknowns regarding fiber stays, PS still prefers wire for this use.)

- Owner retrofits A number of blogs and archive articles from old magazines offer insight into what a retrofit entails. The Windrope family has done an excellent job documenting the addition of a Solent stay to Aeolus , their Gulf 32 Pilothouse sloop.

RELATED ARTICLES MORE FROM AUTHOR

Dear Darrell,

A smaller headsail, or storm jib is indeed preferable to rolling up a Genoa when heading windward in winds over even 20 knots But adding it on as a retrofit brings up the issue of the lines to control it. Ideally it could be fitted on to a self-tacking rail, but these are quite awful if not installed in the original design, just one more thing to trip over and mess up a clean foredeck. I had researched this and apparently there are a number of simple solutions using a rigging set up based on the foot of the mast and clew of the jib, providing just one line astern through a deck organiser to the cockpit ‘piano’. This line simply controls how tight the jib will be and can be left alone when tacking upwind to act as self tacking jib. We sail in the Aegean where wind can be anything from ‘nothing’ to 35 knots sometimes with quick changes, so it pays to be adaptable. If you have any comments or recommendations for such rigs, it may well interest other readers as well and indeed myself as well.

I had a cutter, a Kelly Peterson 44. Great sailing cruiser. However, I would have rather have had a Solient over the traditional cutter. Not even including that yes, it required running back stays, the boat would balance better with a rolled jib over the staysail alone, even with double reefed main. Of course the set of the rollered 110 was not that great. A solient would have been my preference. Walter Cronkite had an interesting custom arrangement on his boat. He had his jib and solient on two stays separated an appropriate distance to properly function and both were on a yoke that would swivel. Just one attachment at masthead and one on stem. Of course hi-thrust bearings on both. The active sail would swivel aft when in use and the inactive would swivel forward complete out of the way! Clever arrangement. Yes, you would get a little “dirty” air from the inactive but everything is a trade off. Probably one that I would take if I could afford all that custom work.

I also have a cutter; CSY 44. When tacking, the jib would not come thru the innerforestay cleanly and would hang up. I installed a quick disconnect and when I know I will be beating it is set up that way. Makes it a lot easier to tack. I see hanging up as a problem with a the double forestay unless you carry the smaller sail on the most forward. However, is this where you want a storm jib? Should I need the storm jib, the staysail stay is the perfect place.

We had a custom rig built for our boat, a Valiant 40′ cutter with a bowsprit that sets the forestay two foot further forward. It was designed to allow both a Solent sail and/or a Staysail. We sail the boat as a Cutter and have no problem at all with the inner forestay interfering with the genoa and jib sheet, (just backwind the staysail until the clew of the genoa has moved to the leward side). The Staysail is roller-reefing too, and is small and very easy to handle, even in a blow. (don’t need the self-tending feature.) When in high winds, the furling staysail is perfect. As for the solent, I consider it more appropriate for a drifter, perhaps wing & wing with the genoa for downwind sailing.

Great Article, Darrell. Your advice to consult a rigger is spot on to address mast support issues. I helped deliver a beautiful Outbound to the Caribbean several years ago from New England. Once we turned south, the skipper set the hank-on Solent staysail on the inner stay. Sweet indeed. Easy to hoist and dowse. Nothing complex about a hank-on headsail. They go up and come down every time.

Interesting article, Darrell. Thank you. But my lord, does anybody proofread this stuff?

As I research adding a solent stay on our Tartan 27 I find many riggers are recommending a 4 to 1 purchase rather than a Highfield lever. They like the ability to adjust the tension at will. For our little sloop with a tabernackle the solent is much simpler and would remain stowed most of the time.

As a cutter sailor I must make a point of clarification. Installing an inner stay or staysail to your sloop design does NOT make it a cutter. A true feature of a cutter is that the mast is further aft than on a sloop in addition to the staysail feature. That is paramount to moving the center of effort further aft as the designer intended.

I have seen a number of cutter owners removing the staysail to sail the boat as a sloop simply because they don’t know how to sail it properly as a cutter. On the other hand, one unnamed circumnavigational sailor calls her boat a cutter when it is simply a sloop with inner stay…the manufacturer never made that boat design as a cutter. Last but not least one prominent cutter manufacturer offered their design as both a sloop and as a cutter; I called them to verify the fact that the mast was still in the original design location as a cutter. Can you begin to imagine what would be involved to design and build a sailboat with optional mast locations or even modify a sailboat from one rig location to the other?

LEAVE A REPLY Cancel reply

Log in to leave a comment

Latest Videos

Island Packet 370: What You Should Know | Boat Review

How To Make Starlink Better On Your Boat | Interview

Catalina 380: What You Should Know | Boat Review

- Privacy Policy

- Do Not Sell My Personal Information

- Online Account Activation

- Privacy Manager

Sailboat Stays and Shrouds: Essential Rigging Components Explained

by Emma Sullivan | Aug 21, 2023 | Sailboat Maintenance

Short answer: Sailboat stays and shrouds

Sailboat stays and shrouds are essential components of the rigging system that provide support and stability to the mast. Stays run from the masthead to various points on the boat, preventing forward and backward movement, while shrouds connect the mast laterally to maintain side-to-side stability. Together, they help distribute the forces acting on the mast and ensure safe sailing .

Understanding Sailboat Stays and Shrouds: A Comprehensive Guide

Introduction: Sailing is an exhilarating experience, but it requires a deep understanding of the various components that make up a sailboat . One crucial aspect that every sailor should grasp is the concept of stays and shrouds. These vital elements not only provide support and stability to the mast but also play a significant role in determining the overall performance of the sailboat. In this comprehensive guide, we will explore everything you need to know about sailboat stays and shrouds.

What are Stays and Shrouds? Stays and shrouds are essential rigging components that hold the mast in place and control its movements during sailing. They primarily serve two distinct purposes – providing support for the mast against excessive sideways forces (known as lateral or side-to-side loads) while allowing controlled flexing, and keeping the mast aligned with respect to both pitch (fore-aft) and roll (side-to-side) axes.

The Difference between Stays and Shrouds: Although often used interchangeably, stays and shrouds have specific functions on a sailboat rigging system. Stays usually refer to those wires or cables that run forward from the head of the mast, attaching it to various points on the bow or foredeck. They help resist fore-and-aft loads placed upon the mast, such as when sailing upwind, preventing it from bending too much under pressure.

On the other hand, shrouds typically refer to rigging lines connecting laterally from both sides of the masthead down towards deck level or chainplates located on either side of the boat’s cabin top or hull. Unlike stays, they primarily counteract side-to-side forces acting on the mast due to wind pressure exerted against sails during different points of sail.

Types of Stays: A typical sailboat may consist of different types of stays based on their location on the mast. Some of the common types include:

1. Forestay: The forestay is a prominent stay that runs from the top of the mast to the bow or stemhead fitting at the boat’s front . It is responsible for supporting most of the fore-and-aft loads acting upon a sailboat rigging system, keeping the mast in position while under tension from sails .

2. Backstay: The backstay runs from the top of the mast to either stern or transom fittings at the aft end of a sailboat. It acts as an opposing force to counteract forward bending moments occurring on larger boats when sailing into a headwind or during heavy gusts.

3. Inner Stays: Found on some rigs with multiple masts or taller sailboats, inner stays run parallel to and inside other stays (such as forestay and backstay). These provide additional support and rigidity when deploying smaller headsails closer to centerline during specific wind conditions.

Types of Shrouds: Similar to stays, shrouds can vary based on their positioning on each side of the masthead and hull structure. Some commonly used shroud types are:

1. Upper Shrouds: These are positioned higher up on a sailboat mast , connecting near its upper section down towards deck level or chainplates for lateral stability against the force exerted by sailing sails.

2. Lower Shrouds: Positioned lower down on a sailboat’s mast , these connect near its midpoint and extend towards lower deck sections or chainplates. They serve mainly as reinforcing elements against lateral forces experienced while sailing in strong winds .

3. Jumpers/Checkstays: Jumpers (or checkstays) are typically temporary shroud additions used when depowering or controlling mast bend in certain wind conditions or point of sail, especially during racing events where fine-tuning sail shape is critical.

Conclusion: Sailboat stays and shrouds are essential components that provide critical support, stability, and control to the mast. Understanding their purpose and types is crucial for every sailor looking to optimize their vessel’s performance while ensuring safe sailing. By comprehensively knowing the role of stays and shrouds, you can confidently navigate the waters while harnessing the power of wind in pursuit of your sailing adventures.

Step-by-Step Instructions for Proper Installation of Sailboat Stays and Shrouds

Installing sailboat stays and shrouds may seem like a daunting task, but with the right knowledge and proper instructions, it can be accomplished smoothly. Stays and shrouds are crucial components of a sailboat’s rigging system that provide support and stability to the mast. In this step-by-step guide, we will walk you through the process of installing these vital elements for safe and efficient sailing.

Step 1: Prepare your Equipment

Before beginning any installation, ensure that you have all the necessary tools and materials at hand. This includes stay wires, turnbuckles, cotter pins, wire cutters, measuring tape, swage fittings (if applicable), wrenches appropriate for your boat’s hardware sizes, and a well-organized workspace. Having everything prepared ahead of time allows for smoother progress throughout the installation procedure.

Step 2: Measure & Cut Stay Wires

Accurate measurements are crucial when it comes to stays and shrouds installation. Using a measuring tape, determine the required length for each stay wire by taking precise measurements from their designated attachment points on deck to the masthead or other relevant attachment points. It is important to leave room for tension adjustment using turnbuckles later on.

After obtaining accurate measurements, use wire cutters to trim each stay wire accordingly. Be sure to trim them slightly longer than measured lengths initially indicated because precision can only be achieved once all connections are made.

Step 3: Attach Wires to Mast Fittings

Now that you have your measured and cut stay wires ready, it’s time to attach them securely to the appropriate mast fittings . Depending on your boat’s design and specific rigging details, this step can vary slightly. Look for pre-existing attachment points designed specifically for stays or fittings specifically configured for thread-on stays if applicable.

Ensure each connection is secure by threading or whatever means necessary as per your boat’s requirements . Double-check that there is no unwanted slack while leaving space for later tension adjustments.

Step 4: Deck Attachment Points

Move on to attaching the stay wires to their designated deck attachment points. These points are usually found near the bow area, and there may be specific fittings designed just for this purpose. Follow your operational manual or consult experienced sailors if you are unsure about the correct attachment points.

Again, double-check that all connections are securely fastened, without any excess slack. It is always better to have a slight bit of extra wire length here than have inadequate length at this stage.

Step 5: Install Turnbuckles

With the stays securely connected at both ends, it’s time to insert turnbuckles. Turnbuckles are essential tools for adjusting the tension in stay wires. Attach these devices to each stay wire by screwing them into the corresponding threaded fitting on either end of the stays. Ensure they are tightened securely but not over-tightened at this stage; you still need room for adjustments and tuning.

Step 6: Secure with Cotter Pins or Locking Nuts

To prevent accidental loosening of turnbuckles due to vibrations or rough sail conditions, make sure to secure them using cotter pins or locking nuts provided by your boat’s manufacturer. Place a cotter pin through the hole located in one side of the turnbuckle and bend it back upon itself, ensuring that it does not interfere with adjacent rigging components or sails.

Alternatively, locking nuts can be used by tightening them against each side of the turnbuckle threads once adjusted correctly –This provides an additional layer of security against unexpected loosening during sailing adventures !

Step 7: Inspect & Adjust Tension

Before hitting the water and setting sail , take a moment to inspect all connections thoroughly. Verify that each wire is properly aligned and does not show signs of damage like frays or kinks—Pay attention to potential chafe points where movement can wear against another object or surface.

To adjust tension, gradually tighten or loosen the turnbuckles as necessary. Be cautious and make small adjustments while periodically checking for an evenly balanced mast, ensuring that it remains straight and true.

By following these step-by-step instructions meticulously, you can ensure a proper installation of sailboat stays and shrouds. Remember to take your time, double-check all connections, and consult with professionals or experienced sailors if any doubts arise. With a meticulous approach and attention to detail, your sailboat rigging will be safe, stable, and ready for smooth sailing adventures!

Frequently Asked Questions about Sailboat Stays and Shrouds: Everything You Need to Know

Have you ever found yourself marveling at the majesty of a sailboat, wondering how it is able to harness the power of the wind and navigate through vast oceans? If you are a sailing enthusiast or considering embarking on a sailing adventure, understanding the intricacies of sailboat stays and shrouds is paramount. In this comprehensive blog post, we will address frequently asked questions about sailboat stays and shrouds, equipping you with everything you need to know.

1. What are Sailboat Stays and Shrouds?

Sailboat stays and shrouds are vital components of a boat’s standing rigging system that help support the mast while ensuring stability during sailing. Simply put, they prevent the mast from toppling over under excessive pressure from the sails or adverse weather conditions. While these terms may sound interchangeable to novices, there are important distinctions between them.

Stays: Stays are tensioned cables or wires attached to various points on the mast and radiate outwards in multiple directions supporting it against fore-and-aft movement. The most common types include forestays (located at the bow), backstays (attached to the stern), side stays (running sideways along both port and starboard sides), and inner forestays.

Shrouds: On the other hand, shrouds provide lateral support to counteract sideways forces acting on the mast. They run diagonally from their connection points on deck-level chainplates outwards towards optimized positions along the spreaders near midway up the mast.

2. What materials are used for Sailboat Stays and Shrouds?

Traditionally, steel wire was predominantly used for both stays and shrouds due to its strength and durability. However, modern advancements have introduced alternative materials such as synthetic fibers like Dyneema or carbon fiber composites. These lightweight alternatives possess remarkable tensile strength while offering corrosion resistance advantages over traditional wire options.

3. How tight should Sailboat Stays and Shrouds be?

Maintaining the appropriate tension in your sailboat’s stays and shrouds is crucial for maintaining integrity and overall sailing performance. Correct tension ensures that the mast remains properly aligned while allowing it to flex as required, absorbing dynamic forces from wind gusts.

To determine optimal tension, consult your sailboat’s manufacturer guidelines or consult with a professional rigging specialist. Adjustments may also vary depending on sea state or anticipated weather conditions . Proper tuning necessitates periodic evaluation to ensure the stays and shrouds’ tension remains within specifications.

4. How do Sailboat Stays and Shrouds affect sailing performance ?

The correct alignment, tautness, and positioning of sailboat stays and shrouds significantly impact sailing performance due to their influence on mast bend characteristics. Adjusting stay tension can control how much a mast bends under load: tightened stays flatten the mainsail’s profile for increased pointing ability in light winds, while looser tensions promote fuller profiles for enhanced power in heavier winds .

Shroud positions also dictate sideways motion of the mast; fine-tuning their tension governs how efficiently a boat can maintain a desired course when encountering various wind strengths and angles.

5. What are some common signs of wear or damage in Sailboat Stays and Shrouds?

As essential as they are, sailboat stays and shrouds are subjected to immense loads that can lead to wear over time. Routine inspection is vital to identify any potential issues before they escalate into major rigging failures.

Signs of wear or damage may include rust or corrosion on metal components, cracked insulation around terminals, broken strands on wire rigging, visible rigging deformation or elongation under load, unusual vibrations onboard while sailing, or creaking noises originating from the mast during maneuvers.

In such instances, swift action should be taken by replacing affected parts immediately or seeking assistance from experienced rigging professionals.

By familiarizing yourself with the essentials of sailboat stays and shrouds, you empower yourself to enjoy a safer and more rewarding sailing experience. Remember to conduct regular inspections, adhere to manufacturer recommendations, and consult professionals when necessary. Now, set sail with confidence as you venture into the salty unknown!

Exploring the Importance of Sailboat Stays and Shrouds in Ensuring Safety at Sea

When it comes to sailing, safety should always be the number one priority. The open waters of the sea can be unpredictable and unforgiving, making it crucial for sailors to have a thorough understanding of their sailboat ‘s rigging system. One vital component of this system is sailboat stays and shrouds, which play a significant role in ensuring safety onboard.

Sailboat stays and shrouds are specialized cables or wires that support the mast, providing stability and preventing it from collapsing under the pressure of wind forces. These essential rigging elements act as a lifeline for the entire vessel, keeping everything intact during even the toughest conditions at sea.

The primary purpose of stays and shrouds is to distribute the load evenly throughout the mast structure. By doing so, they prevent excessive stress on specific areas and reduce the risk of structural failure. This balance is especially critical when sailboats encounter strong winds or rough seas that can exert immense pressure on the mast.

Imagine cruising along peacefully when suddenly you encounter strong gusts of wind. Without properly tensioned stays and shrouds, your mast could bend or break under these intense forces, compromising your safety and potentially causing severe damage to your vessel. Well-maintained stays and shrouds ensure that your mast remains stable even in adverse weather conditions by withstanding these forces without deformation.

However, ensuring that your sailboat’s rigging is reliable isn’t just about maintaining functionality—it demands meticulous attention to detail as well. Stays and shrouds need periodic inspection to identify any signs of wear or corrosion that may weaken their integrity over time. A frayed cable or rusty hardware might not seem like much at first glance, but they could lead to catastrophic failures when put under stress.

Safety at sea also requires understanding how different types of stays and shrouds work together to optimize performance in varying sailing conditions. While staying safe is crucial, performance matters too! Different sailboat designs accommodate different rigging configurations, and knowledgeable sailors carefully select the right combinations to enhance their vessel’s maneuverability. The strategic placement of stays and shrouds aids in controlling the shape and orientation of sails, enabling efficient sailing even in challenging weather.

In this era of advanced technologies, some sailors may wonder if traditional stays and shrouds are still essential with other innovations available. However, it’s crucial to remember that age-old methods often endure for a reason: their reliability. Modern alternatives might offer convenience or weight-saving benefits, but they seldom match the robustness and simplicity of time-tested techniques.

The exploration of the importance of sailboat stays and shrouds ultimately emphasizes the significance of investing time and resources into proper knowledge, maintenance, and selection. As a sailor, prioritizing safety by ensuring the integrity of these critical components can mean all the difference between a pleasurable voyage adrift on calm seas versus surviving treacherous storms.

So, before embarking on any maritime adventure, take a moment to appreciate the unsung heroes that uphold your mast—the sailboat stays and shrouds—and make sure they are ready to bear any challenges that await you on your journey to ensure both safe passage and endless memories at sea.

How Sailboat Stays and Shrouds Impact Performance: Tips for Maximizing Efficiency

Sailboats are fascinating vessels that harness the power of the wind to propel through the water. While many factors contribute to a sailboat’s performance, one often overlooked aspect is the impact that stays and shrouds have on its efficiency. In this blog post, we will dive into the intricacies of sailboat stays and shrouds, exploring how they affect performance and providing valuable tips for maximizing efficiency.

To understand the significance of stays and shrouds, let’s first clarify their definitions. Stays are essentially wires or ropes that provide support to keep a mast in place, preventing excessive bending or swaying. Shrouds, on the other hand, refer specifically to those stays that extend from either side of the boat to stabilize the mast laterally.

While seemingly simple components, stays and shrouds play a crucial role in determining a sailboat’s overall performance. Here’s how:

1. Structural stability: Sailboat stays act as primary supports for the mast, ensuring it remains upright against powerful winds . Without adequately tensioned stays and shrouds, masts can buckle or sway excessively under load, compromising sailing performance and even risking structural damage.

2. Sail shape control: Proper tensioning of stays and shrouds directly influences the shape of your sails while underway. By adjusting their tension appropriately, you can manipulate how your sails fill with wind , optimizing their aerodynamic profile for maximum efficiency. Expert sailors effectively use this control mechanism to fine-tune their boat ‘s speed and responsiveness.

3. Windward performance: Efficiently rigged sailboat stays help maintain proper alignment between mast and sails when sailing upwind (also known as pointing). Tensioned shrouds ensure that minimal lateral movement occurs during tacking or jibing maneuvers when changing direction against the wind. This prevention of excess mast movement translates into less energy lost due to unnecessary drag – ultimately improving windward efficiency .

Now that we’ve established the importance of sailboat stays and shrouds let’s delve into some tips for optimizing their performance:

1. Regular inspections: Routine visual inspections are essential to identify any signs of wear, corrosion, or fatigue on your stays and shrouds. Replace frayed ropes or wires promptly, ensuring that all components remain robust and reliable.

2. Correct tensioning: Achieving the optimal tension in your stays and shrouds is vital. Too loose, and you risk mast instability; too tight, and excessive stress loads are placed on the rigging components. Aim for a tension that allows slight flexibility while maintaining structural integrity – seeking advice from an experienced rigger can help find the sweet spot.

3. Invest in quality materials: The quality of your rigging directly impacts its longevity and performance . Opt for high-quality stainless steel wires, synthetic fibers like Dyneema, or carbon fiber alternatives when replacing old rigging components, as these materials offer superior strength-to-weight ratios.

4. Tuning adjustments: To maximize sail shape control, experiment with adjusting the tension of your stays and shrouds during different weather conditions or sailing angles. Fine-tuning these tensions can lead to significant improvements in both speed and responsiveness while ensuring optimum aerodynamic performance at all times.

5. Seek professional advice: Don’t hesitate to reach out to experts in yacht rigging or naval architects for specialist input regarding optimizing your sailboat’s rigging setup. Their expertise can guide you towards refined techniques tailored to suit specific vessel designs or sailing goals.

In conclusion, understanding how sailboat stays and shrouds impact performance is crucial for any sailor aiming to maximize efficiency on the water. By recognizing their significance as key structural supports influencing sail shape control and windward performance, you can optimize your vessel’s potential while enjoying more thrilling voyages than ever before! So make sure to prioritize regular inspections, correct tensioning methods, high-quality materials, tuning adjustments, and professional guidance to unlock the true potential of your sailboat.

Essential Maintenance Tips for Maintaining the Integrity of Sailboat Stays and Shrouds

Sailboat owners and enthusiasts know the importance of regular maintenance to keep their vessels in top condition. Among the vital components that require particular attention are the stays and shrouds – key structural elements that ensure the integrity of a sailboat’s mast and rigging system.

Stays and shrouds are essentially wires or cables that provide crucial support to the mast, allowing it to properly withstand wind pressures and maintain stability during sailing. As they play such a pivotal role in your sailboat’s performance and safety, it is essential to implement regular maintenance practices to ensure their longevity and functionality.

To help you maintain the integrity of your sailboat’s stays and shrouds, we have compiled some essential tips that will not only enhance their lifespan but also contribute to your overall sailing experience:

1. Visual Inspection: Regularly conduct visual inspections of all stays and shrouds with an eagle eye for any signs of wear or damage. Look for frayed or broken strands, corrosion, stretched areas, or loose fittings. It is better to address minor issues early on rather than waiting for them to become major problems.

2. Tension Monitoring: Check the tension of your stays regularly using a suitable tension gauge or by following manufacturer guidelines. Proper tension ensures optimal performance while avoiding excessive strain on both mast and rigging components.

3. Corrosion Control: Saltwater exposure can accelerate corrosion on metal components like turnbuckles, shackles, or terminals. Routinely clean these parts using freshwater after each outing while inspecting them for signs of rust. Applying protective coatings like anti-corrosion sprays can also significantly extend their lifespan.

4. Lubrication: Maintaining a smooth operation within turnbuckles is crucial for proper tension adjustment as well as preventing corrosion seizing between threaded components (e.g., adjusters). Apply marine-grade lubricants periodically, ensuring even distribution across all moving parts.

5. Regular Rig Tuning: Appreciate the importance of proper rig tuning to optimize sail shape and overall stability. Work with a professional rigger to adjust the tension on your sails and shrouds, correcting any sag or excessive flex.

6. Replacing Components: If you notice any signs of wear that cannot be resolved through cleaning, lubrication, or tension adjustment, consider replacing the affected components immediately with high-quality replacements. Neglecting worn stays or shrouds can compromise your sailboat ‘s safety and performance.

7. Professional Rig Inspection: Schedule a professional rig inspection at least once every two years, especially if you engage in more frequent or rigorous sailing activities. Rigging experts have the experience and knowledge to detect potential weaknesses that may not be readily evident to an untrained eye, helping you avoid costly breakdowns during crucial moments.

Remember, maintaining the integrity of sailboat stays and shrouds should be an ongoing priority for all passionate sailors. By following these essential maintenance tips and providing regular care to these vital elements, you can ensure your vessel is ready to conquer waves with reliability and grace. So set sail with confidence knowing that your rigging system is in optimal condition!

Recent Posts

- Sailboat Gear and Equipment

- Sailboat Lifestyle

- Sailboat Maintenance

- Sailboat Racing

- Sailboat Tips and Tricks

- Sailboat Types

- Sailing Adventures

- Sailing Destinations

- Sailing Safety

- Sailing Techniques

- CLASSIFIEDS

- NEWSLETTERS

- SUBMIT NEWS

The question of staysails - how to make them work for you

Related Articles

- English - United Kingdom

Adding a Staysail? Inner Forestay Setup Options

Published date: august 20 2020.

Are you considering upgrading your sail plan to include a staysail? It is an increasingly popular choice, offering considerable performance benefits, which is explored in more detail in our previous blog here . In this blog we focus on the various setup options and some things to watch out for when considering an inner forestay retrofit.

The primary considerations are fixed or removable stay and furling vs hanked-on. In each case there are pro’s and cons, and multiple set-up options.

Forestay with hanks

Many blue water cruisers, and racers alike, are advocates of the hanked-on staysail – see our previous guest blog on the subject here. There are several variations to consider.

Fixed or removable The simplest option is a permanent, fixed stay with a turnbuckle providing tension. The downside of this setup is that the stay can inhibit tacking with the main genoa, as the clew and sheets must pass around the inner forestay.

To address this, a common solution is a semi-permanent inner forestay. The upper end of the stay is permanently attached to the mast but a quick release fitting at the bottom allows the stay to be brought back to the mast when not in use. Options for tensioning the stay include a highfield lever or 2:1 / 3:1 purchase system led back to a clutch/winch.

N.B. Consideration should be given to the length of the stay. If the length is maximised to the available space, then it will be over-length when brought back to the mast. Alternatively, the stay can be made to fit snugly at the mast and the tensioning system makes up the additional length when in use.

Wire or Composite Inner Forestay Modern materials can provide much nicer and more practical solutions. For a fixed inner forestay on a turnbuckle, the least expensive option is often a wire stay. The same setup is also possible with a fixed composite stay built from PBO or Kevlar. While the cost of these materials may be inhibiting, the benefit of a composite stay is a 75% weight saving plus the soft cover of the cable is kinder on both your staysail and the genoa passing across it during tacking. The staysail should be hoisted on soft hanks.

Another advantage we have seen with this setup is that when the sail is lowered to the deck, the purchase line, on the bottom of the stay, can be eased off and the sail pulled back using the sheet. This pulls the stay towards the mast and can facilitate easier tacking without removing the sail / stay. To re-hoist the staysail – simply tension the stay, release the sail ties and hoist away!

All of the above options also require a staysail halyard sheave box in the mast and sail luff tension is adjusted via the halyard. Furling system

The alternative to a stay with hanked-on sails is a furling staysail. There really is no right or wrong here and it comes down to a personal preference. It is possible to rig a permanent inner forestay with a traditional genoa reefing furler & aluminium luff foils…. But, here at Upffront.com, we like to think these days are over (too much weight!), and a continuous line (bottom-up) furler with torsional cable is the right solution for the vast majority of our customers. There are two primary furler setup options: Hoist on a halyard or into a lock.

The furling unit is clipped directly to a deck padeye. The furled sail is hoisted on the staysail halyard to the required tension. It is common to use a 2:1 halyard to increase control and reduce compression in the mast. A benefit of this setup is that it maximises luff length and allows the sail to sit close to the deck.

This is the simplest and most cost-effective retrofit furling solution. Assuming you have a staysail halyard sheave, the only additional requirement is a dead-end attachment just above the sheave box.

There two options here: Internal or external (hanging) lock:

- An internal lock is the cleanest solution but requires some work on the rig to install the lock. However, this can be done by most good refit yards with some technical verification from your mast maker. The furling swivel is clipped directly to the lock bullet (preferably with a short soft connector) and then a 2/3:1 purchase is required at the tack, to provide stay tension.

- A simpler retrofit is an external / hanging furling lock , lashed to an eye on the mast. The hoist line can run to deck level externally or led into the mast, via a small slot just below the lock, and exited at the mast base with the other halyards. Again, a 2/3:1 purchase system is required at the tack for stay tension.

Karver KF Staysail Furler with purchase system

Retrofit Checklist

Adding a staysail can be a relatively straightforward performance improvement but there are some key checks you should make to ensure the integrity of your mast and rigging.

Deck attachment point - this is fundamental. If you do not have a staysail deck chainplate, talk to your local boatbuilder or refit yard about your options and any structural modifications required to ensure your deck is strong enough to support the inner forestay loads.

Mast fittings – If you do not have the necessary hardware on your mast for the staysail you should seek the advice of your mast maker who can confirm whether any mast stiffening will be required.

Aft rigging – at the same time your mast maker can advise on any requirements for additional aft rigging to counteract the inner forestay loads. On most modern rigs with swept back spreaders this is not generally a structural problem but it is something that needs to be ticked off the check list prior to proceeding with a retrofit project

If you have any questions about code zero and asymmetric furlers, please feel free to email us at [email protected] , or click the link below to see our full range:

Phil Anniss

- There are no suggestions because the search field is empty.

We are constantly reporting on the latest innovations in the marine industry which offer weight savings whilst, at the same time, increasing safety factors. The result: lighter, faster, safer and more exciting sailing.

Recent Posts

Popular posts.

- Furling (55)

- Code Zero Furling (43)

- Karver (40)

- Ronstan (30)

- Electronics (29)

- Blocks and Sheaves (25)

- Sheets (25)

- Winches (25)

- Facnor (24)

- Halyards (24)

- Harken (24)

- Control Lines (23)

- Gottifredi Maffioli (23)

- Dyneema® (22)

- All Purpose Blocks (20)

- Soft Shackles (18)

- Spars and Rigging (17)

- Upffront (17)

- Jib Furlers (16)

- Manual Winches (16)

- Clutches and Organisers (13)

- Mooring and Anchoring (13)

- Spinlock (13)

- Upffront News (13)

- Andersen (12)

- Furling Lines (12)

- Instrument Systems (12)

- Electric Winches (11)

- Loop Products (11)

- Shackles and Fixings (11)

- Armare Ropes (10)

- Morfrac Systems (10)

- Sailing GPS Computers (10)

- Toolkit (10)

- Bowsprit (9)

- Halyard Locks (9)

- Spinnaker Gear (9)

- Winch Handles (9)

- Fenders (8)

- Kohlhoff Rigging (8)

- Standing Rigging (8)

- Structural Furlers (8)

- Tips and Tricks (8)

- Ubi Maior Italia (8)

- Code Zero Furling Sets (7)

- Cyclops Marine (7)

- Oleu Watersports (7)

- Rope Clutches (7)

- Sailing Shackles (7)

- Tylaska (7)

- Velocitek (7)

- Boat Anchors (6)

- Cylindrical Fenders (6)

- Furling Sets (6)

- KZ Race Furler (6)

- Navigation Lights (6)

- PROtect Tapes (6)

- Profurl (6)

- Rigging Projects (6)

- Rope Cleats (6)

- Rope Jammer (6)

- Torsion Cables (6)

- Wichard (6)

- Allen Brothers (5)

- Autopilots (5)

- Boat Compasses (5)

- Code Zero and Asymmetric Furler Accessories (5)

- Deck Organisers (5)

- Mooring Lines (5)

- Outils Ocean (5)

- Premium Ropes (5)

- Racing Halyards (5)

- Racing Sheets (5)

- Robline (5)

- Round Fenders (5)

- Runner Blocks (5)

- Sailmon (5)

- Top-Down Furler Sets (5)

- Trogear (5)

- Anchor Chains (4)

- B&G (4)

- Backstay Cables (4)

- Cam Cleats (4)

- Digital Load Cells (4)

- Electric Furlers (4)

- Fenderess (4)

- Ferrules and Rings (4)

- Headfoils (4)

- Industry News (4)

- Morfblock (4)

- Reef Hooks (4)

- Snap Shackles (4)

- Structural Furler Accessories (4)

- Backstay (3)

- Bottom-up Furler Sets (3)

- Bullet Locks (3)

- Calypso Electronics (3)

- Cousin Tresec (3)

- Electric Winch Accessories (3)

- Fairleads (3)

- Flat Fenders (3)

- Foot and Cheek Blocks (3)

- Headsail Furling (3)

- Individual parts (3)

- Instrument Displays (3)

- Internal Locks (3)

- Life Jackets (3)

- Lifelines (3)

- Lopolight (3)

- Novasail (3)

- Race Computers (3)

- Sail Hanks (3)

- Sail Hardware (3)

- Sailing instruments (3)

- Snatch Blocks (3)

- Snuffers (3)

- Tiller Extensions (3)

- Tuff Luff and Harken Sets (3)

- TuffLuff (3)

- UK Sailmakers (3)

- Wireless Modules (3)

- Autopilot Drives (2)

- Black Box Snuffers (2)

- Boat Fairleads and Organisers (2)

- Clutch units (2)

- Cutter Rig (2)

- Ewincher (2)

- Excrusion Only (2)

- External Locks (2)

- Fiddle Blocks (2)

- Fixed Tiller Extensions (2)

- Foredeck Club (2)

- Future Fibres (2)

- Grab Bags (2)

- Hall Spars (2)

- Handheld VHF Radios (2)

- Ino-rope (2)

- Lash Thimbles (2)

- Life Jacket Accessories (2)

- Main Halyard Shackles (2)

- Mainsheet Purchase systems (2)

- Mantagua (2)

- PTFE Tapes (2)

- Padeyes (2)

- Polyform fenders (2)

- Resins, Lubes and Gels (2)

- Rope Bags (2)

- Safety Lines (2)

- Sailing Dogbones (2)

- Seasure (2)

- Sheaves (2)

- Soft Hanks (2)

- Solent Rig (2)

- Southern Spars (2)

- Storm Sails (2)

- Tellescopic Tiller Extensions (2)

- Tiller Pilots (2)

- Top down sets with stay (2)

- Winch Feeders (2)

- fendress (2)

- 3:1 Purchase (1)

- ACR Electronics (1)

- Alphalock (1)

- Autohelm Processors (1)

- Backstay Tensioners (1)

- Boom Vangs (1)

- Bow Shackles (1)

- Carbo-Link (1)

- Clevis pins (1)

- Clutch Parts (1)

- Clutch Repair Kits (1)

- Continuous Furling Lines (1)

- D-Shackles (1)

- DCSolar (1)

- DrSails (1)

- Dyneema® Covers (1)

- Electronics Accessories (1)

- Fendertex (1)

- Fids and Spikes (1)

- Flipper (1)

- Fourthcape (1)

- Halyard Blocks (1)

- Horn Cleats (1)

- Jackline (1)

- Jib Furler Accessories (1)

- Lead blocks (1)

- Life Jacket Spares (1)

- Low Friction Rings (1)

- Mainsail Furling (1)

- Manual Genoa Furlers (1)

- Navisafe (1)

- Polyform (1)

- Polyform US (1)

- Prism 2 (1)

- Reckmann (1)

- Rigging Tools (1)

- Rigid Boom Vangs (1)

- Rope Covers (1)

- Rope Purchases (1)

- Sailing Dinghy Tape Kits (1)

- Sailserver (1)

- Schaefer Marine (1)

- Single Furling Lines (1)

- Smartlink (1)

- Smarttune (1)

- Solar Power (1)

- Staysail (1)

- Strops and Loops (1)

- Swivel Locks (1)

- Tikal Tef-Gel (1)

- Top-Down Adapters (1)

- Torsion Ropes (1)

- Vakaros (1)

- Winch Service Accessories (1)

- Wired Navigation Lights (1)

- fender covers (1)

- Customer Support

Payment Methods

- Testimonials

- News & Blog

- Download Centre

- Image Credits

- Terms & Conditions

- Privacy Policy

- Interest Based Ads

- +49 431 2202140

- : [email protected]

- MarketPlace

- Digital Archives

- Order A Copy

Adding a staysail

Staysails are an evolution of the many different jibs flown by commercial ships in the age of sail. Their history on yachts has had many incarnations. Many voyaging sailboats could benefit from the addition of a staysail to a single headsail sailplan.

Adding a staysail gives a boat a small jib that can balance the boat in heavier wind and sea conditions. We’ll take a look at some of the factors to be considered for this sort of an improvement.

Sometimes staysails are flown with a loose foot, and sometimes on a boom or “club.” They are also set up self-tacking to a jib-horse or track, and sometimes set overlapping the mast so that they need to be tacked around like a genoa. On larger foredecks skippers often fly them inside a full jib, sailing the boat as a double-headed rig and gaining reaching power. Still others use them as small jibs for heavy weather because they consolidate the sailplan and lower its center of effort, while giving the crew a more central and safe location at which to work when taking seas on deck.

Take the example of a voyaging couple who bought an older Tartan 34. They purchased the boat in Long Island Sound and decided to use their summer vacation to deliver it home to New Jersey via Newport and Long Island’s south shore.

On the leg from Block Island to Ambrose Light, the couple discovered that their boat had a tendency toward lee helm, even with just a full main and a working jib set. In this case, a smaller sail, set further aft on the foredeck would help to balance out the helm, making the boat manageable in a seaway in heavy air.

As with any rig alteration or addition, we want to consider the balance of the boat, so that we can maintain desirable helm with the new sail combination. If we can decide what wind ranges we aim to use the sail in, then we can get some idea of what sail combinations we would fly in those conditions, and, therefore, how the boat will balance with a given staysail.

A copy of a boat’s sailplan – obtained from the designer or builderandmdash;can be used to determine how a staysail will affect overall sailing characteristics. Our voyaging couple received their boat’s sailplan from the builder and it quickly revealed the cause of their ill-balanced helm. The boat was originally designed as a yawl. In the early 70s, when the boat was built, this configuration was not popular and the boat was offered as a sloop rig, which moved the sailplan’s center of effort farther forward.

Consideration should be given to where the new inner forestay is intersecting the foredeck and rig. I like to keep the new inner forestay parallel to the primary headstay for aesthetic reasons. The more room one has between the inner and outer headstays, the less the inner headstay will interfere with the tacking of a full genoa. Also, the farther back on the foredeck the sail is, the more protected crewmembers will be when setting and dousing the sail in bad weather. Conversely, the farther aft along the deck the tack is, the smaller the sail will be, and the less power it will generate. If one makes the sail too small, it will only be useful as a heavy weather sail.Rig considerations

Adding an inner forestay to a rig means that one is introducing forward and leeward bending moments to the spar in a place where it was probably not designed to deal with them. Remember that most spars are designed to take compression, all horizontal loads must be accounted for by the standing rigging.

If one has a double-spreader rig, and the new inner forestay intersects the spar at or close to the upper spreader, then a set of running backstays can be used to support the rig when the staysail is set. Spectra or an aramid rope is a good choice for the runners for several reasons: they add only a fraction of the weight aloft, don’t punish the rig and mainsail as severely as wire, and are easily spliceable. The drawbacks are that they can cost a bit more and probably won’t last as long as well-maintained wire.

The Tartan 34 rig has only a single-spreader rig, but the relatively small size of the required staysail allowed us to bring the forestay in just a little ways above the spreader. This particular rig, for example, had only one set of lower shrouds and no intermediate fore and aft support. Because of that, the addition of running backstays will greatly reduce the rig’s tendency to pump (something those old CCA rigs are very good at). Tying the runners into the deck as far forward as possible, while still maintaining a 15 degree shroud angle (the angle between the mast and the wire), helped us give the rig a bit more transverse rigidity to deal with the new load.

If the forestay intersects the spar at a point somewhere in the middle of a panel, then a set of diamonds or an intermediate shroud to give the section support athwartships might be a good idea.

Whatever is done, one will have to add a fitting to the spar that can take up the new forestay. This fitting must conform to the forward shape of the spar section and should probably have holes in it where one can attach toggles or link plates to the after corners of the fitting and pick up the running backstays. A local rigger can help in ordering a fitting from a place like Metal Mast Marine in Putnam, CT. I prefer to fasten the fitting to the mast with machine screws by drilling and tapping the spar, but many riggers prefer rivets. Whichever type of fastener is chosen, it’s still a good idea to bed the fitting in a polysulfide compound.

A new forestay can be terminated in any manner but I prefer the Norseman or Stalock style of mechanical fasteners. They are very strong, can be done at home, and the whole thing is reusable (with the exception of the cone, which is relatively inexpensive).

Make sure that the connections are toggled top and bottom to allow a free range of motion. Otherwise, the fittings and the wire will be unduly stressed and will tend to fatigue at the connection point to the terminal fitting.

One option is making the lower end of the forestay removable. This way, it can be released and set aside to the shrouds when not in use. Release fittings for inner forestays are commercially available, but expensive. Many people just use a turnbuckle with a quick pin. (Make sure to retain the quick pin on a lanyard to avoid losing it.)

If the inner forestay is set up to be removable, be sure to protect the spreaders and the mast from abuse by the wire. I’ve seen poorly secured inner forestays, and wire halyards wear through the leading edge of spreaders as they slap and chafe against a pitching spar.Tying in to the deck

An inner forestay needs a chainplate to provide secure integration into the boat’s structure in the same way as the primary headstay and shrouds.

Sometimes it is convenient to tie this headstay into an existing bulkhead, such as the one that divides the v-berth from the forepeak on many boats. In this case, we must remember that the bulkhead, even if structural, is not designed to take the afterward shear loads that will be placed on it by the chainplate. The fastening should be braced from pulling aft so that the deck is not loaded excessively. If improperly done, it can lead to leaking at the chainplate and deterioration of the deck core and the bulkhead. Proper fastening can be accomplished by attaching the chainplate to the deck in the form of a through-bolted extra heavy padeye, backed by an angle bracket that is tied to the bulkhead. This approach will both clamp the deck with a sealant gasket and distribute the chainplate’s bite over a larger section of deck.

The inner forestay does not always fall at a convenient spot on the deck, and it is under these circumstances that we must take the time to supplement the structure of the boat to securely tie the headstay into the boat. If there is no V berth up forward and the space is used for sail stowage, we may be able to get away with a simple “tie rod” from the under side of the deck to the keel. Tie rods can be made of rod or chain of at least two-and-a-half times the strength of the wire that will be used in the rigging. The tie rod should carry the same angle as the headstay it is reinforcing. If tying into the boat’s keel or stem is impractical, than we can split the tie and carry the load to inward-facing, heavy-duty padeyes that are above the waterline on both sides of the hull. Full backing plates and plenty of polysulfide caulking to seal and reinforce these bottom padeyes is the way to go if this approach is employed. One should also glue some heavy plywood to the inside of the hull to help spread out the new loads. On the top end the loads can be transmitted through the deck by two heavy padeyes back to back with lots of polysulfide.